Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction represents a mammoth task. Its successful implementation will depend, inter alia, on Ukraine’s ability to attract private sector support for its reconstruction projects. To enhance the country’s investment attractiveness, the European Commission put forward a €50bn Ukraine Facility proposal for 2024-2027. Will this initiative suffice to uncover Ukraine’s investment potential? In this policy brief, Sascha Ostanina maps proposed EU investment incentives for Ukraine and analyses shortcomings in the current approach. Fine-tuning its assistance mechanisms requires the EU to help Ukraine set-up insurance mechanisms, expand sector-specific SME financing mechanisms, and to prioritise Ukraine’s access to the EU single market. Getting this right could not only mobilise private investment for Ukraine’s reconstruction, but also streamline Ukraine’s accession to the EU.

Ukraine and the European Union are up for a good start to rebuild Ukraine’s invasion-devastated economy and infrastructure. At the Ukraine Recovery Conference in London in June, Ukraine presented a roadmap that managed to balance the country’s reconstruction needs with the West’s funding capabilities. In its turn, the European Commission put forward a proposal to commit €50bn in grants and loans for Ukraine’s recovery and reconstruction by 2027. In the meantime, the EU joined two more initiatives to help attract private capital to the war-torn country.

These fresh assistance measures for Ukraine reflect mutual understanding that, on their own, public funds will not be enough to rebuild Ukraine. According to the World Bank, Ukraine needs €383bn in reconstruction and recovery to repair damages inflicted during the first year alone of Russia’s invasion. This sum does not account for the destruction of the Nova Kakhovka dam in early June. Only a quarter of this money is required for sectors traditionally financed by public spending, such as public building reconstruction and demining. The private sector would take on the rest. At the Conference in London, 400 global companies pledged to support rebuilding Ukraine’s economy. However, only a few firms have so far dared to go ahead .

Russia’s continuing war in Ukraine does indeed deter private investors but this terrible event does not account for all obstacles to investment. Hence, the EU can already assist Ukraine with investment incentives, without waiting for the end of the war. The newly proposed EU initiatives for Ukraine provide a delicate medium-term nudge to investors and non-financial companies to re-evaluate – or even discover – Ukraine’s market. But to turn them into a longer-term pro-investment strategy, the EU needs to adopt a less risk-averse approach. There are three specific arrangements that the EU could already ramp up: support mechanisms for Ukraine’s insurance market, financing small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and access to the EU single market. These measures should help Ukraine foster flows of foreign direct and domestic investment, especially in the most heavily war-affected regions and sectors.

Part I. Ukraine Needs annual 14% GDP Growth for Five Years to Recover

Ukraine needs €383bn just to recover from physical infrastructure and economic damage induced during the first year of Russia’s invasion (excluding losses caused by the Nova Kakhovka dam destruction.) According to the World Bank, the costs of a 10-year nationwide reconstruction programme will surpass Ukraine’s 2022 GDP almost threefold. Rebuilding Ukraine will require sustained 14% GDP growth for five years after the conflict, the EBRD has calculated. If those numbers tell us very little in real terms, look at this aerial video of the obliterated city of Bakhmut, which used to house 80,000 inhabitants, the country’s largest rock salt deposits, and a winery.

A country-wide scale of destruction

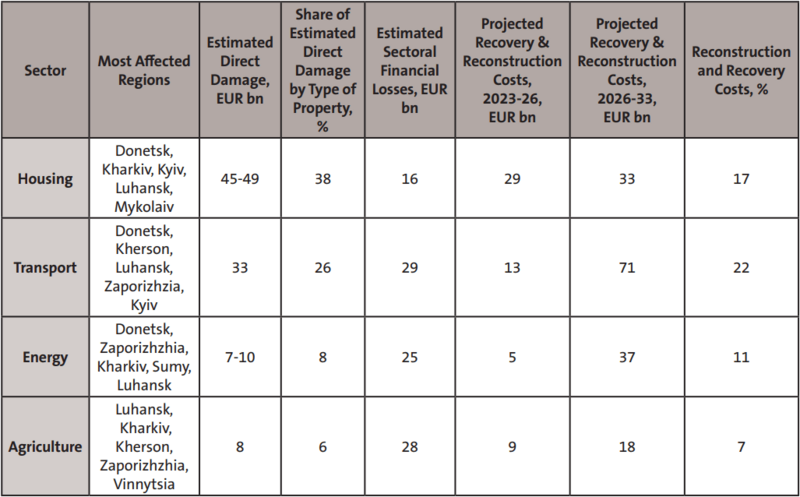

Russia’s invasion crippled all sectors of Ukraine’s economy but four sectors bore the heaviest brunt: housing, transport, energy, and infrastructure (see Table 1). Their destruction became Russia’s key military objective in summer 2022. Failing to entrench in occupied Ukrainian territories, Russia’s army switched to deliberate long-range UAV (drone), aircraft and missile strikes on critical and civilian infrastructure.

Housing. During the first year of Russia’s invasion, Ukraine’s housing sector lost, partially or completely, around 8-9% of its total housing stock. These 1.3mn buildings used to house 3.2mn people. This corresponds to almost the entire population of Berlin (3.4mn) or more than that of Paris (2.2mn) and Marseille (over 850,000) combined. Almost 90% of these homes are private houses, and over a third damaged beyond repair.

Transport. From summer 2022, Russian missile and UAV attacks targeted two types of Ukrainian transport infrastructure. First, assets in frontline areas subject to positional fighting in the regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, and Kharkiv. Second, critically important logistics infrastructure used to supply frontline territories, such as airports, airfields, railway and highway assets, sea and inland ports.

Energy. Ukraine’s energy supply sector amounted to 7-8% of the country’s GDP before the war. Since 2022, Russia has destroyed or severely damaged 40% of its electricity transmission infrastructure and a large share of the country’s power generation capabilities. Ukraine lost all its coal and hydroelectric power plants, 13 combined heat and power plants, and two-thirds of its renewable energy infrastructure.

Russia’s armed forces also seized control over the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, the largest operating nuclear plant in Europe that generated about 20% of Ukraine’s electricity, and four coal power plants. Consequently, some 12mn Ukrainian households lost access to, or experienced shortages of, electricity, water, gas, and heating supplies during the 2022-2023 heating season. On average, Ukrainians experienced five cumulative weeks with no electricity in October-December 2022.

Agriculture. Ukraine’s agriculture sector sustained heavy economic disruption. Pre-invasion, the sector produced 10% of the country’s GDP, employed 14% of its labour force, and generated over 40% of its exports. In 2019-2020, Ukraine exported 57mn tonnes of grain, or 16% of global grain exports. Russia’s invasion disrupted Ukraine’s wheat harvests planted in 2020-2022 and future harvests for years to come. Ukraine’s agriculture recovery is also impeded by severe damage of seaport infrastructure, storage facilities, and the fertiliser industry.

Part II. What Hurdles Foreign Direct & Domestic Investment to Ukraine?

Ukraine’s long-term vision is evident: to turn a Soviet-designed, Russia-shattered country into a hub for Europe’s green and digital transformation. To that end, Ukraine already identified key sectors to attract investment: transport infrastructure, mass industrial production, high value-added agriculture, emerging IT projects, hydrogen energy and other REW, electric vehicles, digital infrastructure. However, this transformation will be a mammoth task for two reasons: Ukraine needs first to ensure its security and territorial integrity and then, skyrocketing economic development.

There is no way to avoid this topic: Ukraine needs sustainable cessation of fighting to attract private investment in support of its reconstruction. On other words, it is critical for Ukraine to first achieve basic levels of human security, or negative peace defined as “the absence of violence or the fear of violence.” Then, Ukraine can start working on achieving positive peace resulting in “better economic outcomes, measures of well-being, levels of inclusiveness and environmental performance.” At the moment, Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction has statistically only a 20% success rate. According to the EBRD, only one in five economies emerging from an armed conflict has enjoyed at least 25 years of lasting peace. Hence, only a minority of countries managed to successfully conduct post-war reconstruction. Additionally, even if/when Russia’s armed forces withdraw from all Ukrainian territories, the risks of long-range attacks from Russia will remain. Since February 2022, Russian long-range bombers, artillery, missiles and drones have been striking critical infrastructure and residential areas in 25 of 27 Ukrainian regions. Ukraine’s limited air defence warfare capabilities can only effectively protect the capital of Kyiv and a few strategically important infrastructure assets across the country. To beat the odds of post-conflict reconstruction, Ukraine needs unambiguously positive security guarantees, which will commit all its Western allies to help Ukrainian forces repel Russian military attacks.

The second part of the reconstruction equation is Ukraine’s ability to boost its economic, institutional, and human capital developments. In 2016-2021, FDI inflows represented 3.3% of Ukraine’s GDP, a level roughly on a par with that of the EU’s Poland (3.5%), Bulgaria (3.3%), and Romania (2.9%). According to the EBRD, Ukraine will need to drive up its ratios of investment to GDP from an average 16% in 2016-2021 to 30-35% to the tune of 20% of GDP, or €47bn (in 2023 prices) per annum. In actual numbers, Ukraine is estimated to require €170bn in FDI and €325bn in domestic private investment to finance a 15-year reconstruction phase.

What stands in Ukraine’s way of attracting foreign and domestic investment for its reconstruction? This policy brief does not seek to analyse such long-term processes as ensuring Ukraine’s military security or its EU-aligned institutional reforms. Instead, it focuses on economic incentives to help Ukraine mitigate existing market drawbacks, while working on achieving these longer-term objectives. With that scope in mind, there are three main market impediments: a shortage of risk-sharing (re)insurance offers; limited access to SME financing mechanisms; and unstable access to the EU’s single market.

Crippled (re)insurance market in Ukraine

A sustainable insurance market is a precondition to design and successfully implement a long-term reconstruction programme. Insurance encourages long-term planning and innovation by spreading risks over time through transfer or pooling. Additionally, insurance contributes to the availability of financing and reduces the need for loan workout and bankruptcy procedures. Reinsurance companies further reinforce this market stability by insulating insurance firms from major claims.

Ukraine’s insurance market is currently unfit to fulfil these functions. The country lagged behind Europe in its insurance density level even before the invasion. In 2015, insurance policies covered only 10-15% risks in Ukraine. By way of comparison, the most developed countries have a 90-95% insurance density rate. Under these circumstances, Ukraine understandably sparked scant interest among reinsurance firms.

Ukraine’s insurance market conditions first worsened in 2014. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the start of the Donbas conflict, most of the 20 largest international private insurers stopped providing coverage. Russia’s 2022 invasion forced them to enact further risk-aversion measures. Insurers stopped covering assets in Ukraine under war exclusion clauses. Reinsurance firms simply imposed a blanket moratorium: Ukraine lost 12 of 13 major ship insurance companies and aircraft insurance providers. The country’s domestic insurance companies survived mostly due to their solvency, liquidity and flexibility in providing out-of-pocket insurance coverage.

Since the invasion began, insurance companies have launched only one war-time insurance product in Ukraine: a Black Sea Grain Deal risk-sharing mechanism. In summer 2022, the UN and Turkey negotiated partial restoration of Ukraine’s grain exports from its Black Sea ports that remained blockaded by Russia. The deal’s €46mn insurance package came from three international insurers: Marsh brokered the agreement, Ascot serves as the lead underwriter, and Lloyd uses their licensing systems to enable risk-sharing.

To offset the obvious drawbacks in Ukraine’s insurance market, the UK, Germany, and France are designing war insurance mechanisms. If approved, they will complement scattered investment guarantees schemes that EU member states are using to derisk domestic businesses working in or with Ukraine. Poland’s export credit agency KUKE, for instance, is insuring receivables under export contracts with Ukrainian buyers. France’s Banque Bpifrance Assurance Export agency provided state guarantees for supplies of seeds and domestically-manufactured goods for Ukraine’s infrastructure repairs. Germany covers 11 investment projects, worth €221mn, in Ukraine, and has 21 more applications in the pipeline. However, this scattered, bilateral approach cannot substitute a comprehensive insurance market.

Mismatching demand and supply of SME financing tools

Prior to Russia’s 2022 invasion, Ukraine’s SMEs amounted to 99.9% of the total business population. SME firms employed over 7.4mn people, or 82% of the labour force, and accounted for 65% of sales of goods, works, services and value added. Despite their economic significance, Ukrainian SMEs tended to have only a short-term investment planning horizon. Businesses opted to finance investment with domestic savings due to rigid banking sector regulations, foreign currency restrictions, and highly infrequent availability of private equity and venture capital. As a result, the funding gap between demand for and supply of SME financing grew from €9.3bn to 10.3bn in 2016-2021.

Interestingly, this financial gap accumulated, when the EU was purposefully increasing its SME financing projects in Ukraine. This likely occurred due to a low efficiency level of EU outreach campaigns. A 2018 study found that some 30% of Ukrainian SMEs did not know about support programmes for their development. These results were demonstrated even in western, most EU-oriented Ukrainian regions. A small-scale SME survey in Lviv district, bordering Poland, also found that 46% of companies had never used external financing. Two main explanations were offered: respondents either did not know about financing support programmes or mistrusted them, opting to rely on their own equity or long-term bank loans.

Russia’s full-scale war depleted domestic business savings and reduced availability of bank loans and business equity. In response to the invasion, Ukraine’s central bank raised the key interest rate to 25% and retains it at that level Consequently, the country’s largest public bank, PrivatBank, recorded a drop in the share of investment lending from a pre-war 40% to 17% in 2022. At the moment, interest rates for corporate loans denominated in the national currency, the hryvnia, sit at around 20% and in foreign currencies at 8-9%. The latter are practically unavailable for Ukrainian SMEs due to repeated currency value losses. Understandably, 59% of Ukrainian businesses consider loans to be inaccessible or barely accessible, while a further 31% of respondents hesitate to even think of loans.

Closing the SME financing gap will also require the EU to account for a war-distorted business landscape in Ukraine. Russia’s invasion effectively halted business activities in Ukraine’s east: in March 2022, only 13% of SMEs were still working, and 42% fully suspended their operations. Some of these companies decided to relocate to safer regions. In summer 2022, over 200 businesses moved from the eastern to central and western parts of Ukraine; 800 more firms applied for government support to resettle. As a result of forced relocations, Ukrainian companies had to redesign their supply and logistics networks or even completely change the profile of their business activities. Consequently, the average decline in the value of exported goods amounted to over 60%, lowering business revenues by nearly 80%. War-time business relocation will likely bias regional recovery and reconstruction processes, accentuating the financial disparity between Ukraine’s east and west.

Unstable access to the EU’s single market

The EU and Ukraine commenced provisionally applying a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) in 2016. The agreement lowered the majority of tariffs for trade in goods and simplified customs procedures. However, the EU maintained import tariffs and tariff rate quotas for a number of industrial and agricultural goods, such as certain foodstuffs, vehicles, copper and aluminium articles, fertilizers, electrical equipment. Additionally, non-tariff measures such as technical barriers to trade and (phyto)sanitary measures remained in place, affecting some 4-17% of Ukraine’s exports to the EU.

Due to Russia’s 2022 invasion, the EU temporarily fully liberalised its trade with Ukraine in June 2022. The Union suspended import duties, quotas and trade protection measures to offset war-blocked trade flows from Ukraine. In 2023, this preferential trade regime, as well as liberalisation of freight transport by Ukrainian carriers, was extended until June 2024. This limited extension neither supports the EU’s intentions to commit to Ukraine’s reconstruction, nor helps investors in Ukraine to plan long-term. Additionally, the preferential trade regime came this time with a caveat: temporarily re-introduced import restrictions on some grain and seeding material. Five “frontline” EU member states, namely, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania, successfully lobbied for these restrictions. Ukraine’s agriculture, one of its key economy sectors, has allegedly disrupted their economies and aggravated logistical bottlenecks.

The introduction of trade barriers sets a dangerous precedent for the reconstruction period. Investors, especially in sectors that still suffer from export restrictions under the current Free Trade Agreement, need to know for certain that access to the EU market will be guaranteed. Existing research confirms this need for long-term stability. Studies indicate that a country’s accession to the EU’s single market has the second largest positive impact on FDI inflows, after EU membership itself which brings a 60% increase in investment.

Part III. The EU Moved from Emergency Relief to Medium-Term Planning

Since the invasion began, EU aid for Ukraine has totalled €72.3bn. Of this, €38bn, almost exclusively in loans, has supported Ukraine’s economic recovery; €17.3bn for military and humanitarian aid; and €17bn to assist EU member states with Ukrainian refugee inflows. By way of comparison, these are EU member states commitments for energy subsidies in 2022: Germany - 264bn; Italy – €80bn; France – €50bn; the Netherlands – some €40bn.

Initial designs of EU medium-term reconstruction support measures

In June 2023, the European Commission presented its first funding proposal aimed at addressing Ukraine’s short- and medium-term reconstruction needs. A Ukraine Facility instrument envisions the gradual allocation of €50bn in loans and grants in 2024-2027. The Facility is organised around three pillars:

- Pillar I – financial support for Ukraine’s financial sustainability in exchange for reforms aligned with the EU accession process

- Pillar II – a specific Ukraine Investment Framework to attract and mobilise public and private investments for Ukraine’s reconstruction

- Pillar III – technical assistance and other supporting measures

The EU’s Ukraine Facility follows the example of the Recovery and Resilience Facility under NextGenEU. It envisages that the Ukrainian authorities lay out a plan for the country’s EU-aligned reform, recovery and reconstruction, subject to EU assessment and adoption. The Facility’s Pillar II, the Ukraine Investment Framework, should also adumbrate recovery and reconstruction projects that will facilitate the plan’s implementation. This section will likely reflect the priorities identified in the recently proposed Ukraine Development Fund. It aims to attract capital to five key sectors: energy, infrastructure, agriculture, manufacturing, and IT. If the Commission’s proposal is approved, the EU will start allocating money to Ukraine as soon as next year.

In the meantime, the EU combined two further instruments to mobilise private capital for Ukraine. The European Investment Bank (EIB), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and the International Finance Corporation (ICF) signed a €800mn agreement to finance recovery of Ukraine's economy, energy and municipal infrastructure. Over €355mn will support Ukrainian SMEs in forms of loans and guarantees. Separately, the EBRD and the European Commission, among other actors, agreed to “explore the possibility” of setting up a Ukraine Recovery Guarantee Facility. If it goes ahead, it will work to facilitate access to war-risk insurance for Ukrainian and international firms with an initial focus on trade and international shipping.

Shortcomings of proposed investment incentivisation measures

These proposals signal an important EU policy shift on Ukraine: from providing short-term emergency relief aid to designing the country’s medium-term recovery framework. Still, this does not by itself establish a foundation for a longer-term EU investment incentivising strategy. To do that, the EU should adopt a less risk-averse approach and ramp up its assistance mechanisms for Ukraine’s insurance market, small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and access to its single market.

Set-up insurance mechanisms beyond war risks and trade

The Ukraine Recovery Guarantee Facility is so far the largest attempt to design a multi-actor insurance scheme to risk-insulate a whole sector of Ukraine’s economy: trade. However, until it is up and running, this measure is unlikely to incentivise investment in Ukraine due to the absence of insurance coverage details and an execution timeline. A tailor-made investment insurance facility for Ukraine also needs an international institution to direct actions and ensure accountability.

In practical terms, the EU and its institutions should participate in setting up and running such an investment insurance facility for foreign and domestic investors in Ukraine. EU-supported insurance mechanisms for Ukraine should also expand beyond the current focus on protecting trade in wartime. In the next 15 years, four-fifths of Ukraine’s €500bn foreign and domestic investment will require investment insurance. Hence, Ukraine needs two types of (re)insurance mechanisms to attract investment: for flagship projects in the economically prioritised sectors, such as agriculture or infrastructure, and “pocket-sized” insurance policies for Ukrainian SMEs, especially those working in eastern regions.

An insurance facility for Ukraine should also be designed from the very beginning to cover, in addition to war, the risks of political violence and terrorism. Their exclusion will limit proposed protection mechanisms to, strictly speaking, invasions, revolutions, and military coups. However, Russia’s military involvement in Ukraine’s Donbas conflict in 2014-2022 demonstrates the need for insurance policies oriented towards political violence. If designed in this larger format, the insurance facility will signal to investors that, even if Russia formally suspends its “special military operation” but continues its involvement in Donbas-type localised conflicts in Ukraine, their assets and personnel will still be protected. Without the need for additional time-consuming negotiations by EU institutions.

Expand sector-specific SME financing mechanisms

The Ukraine Facility’s Pillar II intentions are clear: to establish a Ukraine Investment Framework to attract investments for Ukraine’s reconstruction. However, the proposal so far contains no clarity about its aid format or financial incentives, as the EU is waiting for Ukraine to design its recovery plan. At the moment, the only guaranteed EU assistance for Ukrainian SMEs is €355mn from the EIB, EBRD, and IFC support mechanism. This assistance is a lifeline for Ukrainian businesses now; but it does not allow them to plan over the medium-term.

The EU needs to ensure that Ukraine’s recovery plan, designed in line with the Ukraine Facility objectives, has a strong focus on the SMEs. Their prioritisation is important for two main reasons. First, they are the backbone of the country’s economy amounting to 99.9% of the total business population. Second, existing research demonstrates that the relationship between firm size and their risk-proneness is U-shaped. There are two types of companies ready to invest in a conflict-affected area: large firms, interested in global investment projects, and small, less-established companies.

Support measures for SMEs need to focus on enhancing the availability of funds for those industries contributing the highest amount of value to overall national output . In Ukraine, these are retail and services, including logistics, industry, and agriculture. Additionally, these businesses are generally more eager to invest in (post-)conflict countries, as are firms working in the telecoms, construction and mining sectors. Public data also indicate that Ukraine’s economic sectors such as trade, production, processing, transport and logistics are especially loan-hungry at the moment. Ukraine’s experience in running SME support programmes, financed domestically or by individual EU member states, should be used to identify the most appropriate support formats for Pillar II.

Any medium- and long-term assistance measures should be clearly geared towards regions in eastern Ukraine. These have sustained the greatest war damage and, hence, are in need of larger public funding and more generous private investment incentives. Hence, EU SME support mechanisms need to support businesses’ relocation, relaunch, and reconversion there. As military fighting continues, if launched now, these measures are unlikely to bring any immediate tangible effects. However, if the EU designs its Ukraine Facility without prioritising eastern Ukraine, it will exclude those regions from benefiting from a tailor-made €50bn assistance package until 2027, regardless of security on the ground. This will further increase the financial disparity between Ukraine’s east and west. To avoid this, the EU should already design a Ukraine Facility adjustment mechanism to be able to revise the facility at any given time between 2024 and 2027.

Additionally, all SME-targeted programmes should be complemented with promotion campaigns and assistance provision, for instance, for developing funding applications. These measures could be part of the Ukraine Facility’s Pillar III and should be implemented at regional and municipal levels to further empower Ukraine’s decentralisation reform. This will also help EU better integrate Ukrainian SMEs into the EU single market.

Prioritise Ukraine’s access to the EU single market

None of the fresh EU initiatives addresses this challenge: that Ukraine is expected to turn into a magnet for foreign investment without guaranteed full access to the EU single market. Effectively, the EU limits the corporate planning horizon to a maximum of one year, or until June 2024, of the “fully” liberalised trade regime with Ukraine. This contradicts the EU’s commitment to assist Ukraine’s post-war recovery and reconstruction.

There is only one sustainable solution: the EU should suspend all barriers for Ukraine’s exports to the EU for the long-term. Trade regime liberalisation should also be complemented by institutional support. For instance, the Ukraine Facility’s Pillar III could be used to facilitate an effective nation-wide monitoring network to assist Ukraine in enhancing its capabilities to fully monitor the implementation of EU single market requirements. The next step towards single market accession could be accepting Ukraine into the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). The association currently comprises Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, and Lichtenstein (which would have to approve it). However, it should be clearly articulated that EFTA accession is no substitute for EU membership. It is there to help Ukraine attract private investment for its reconstruction, while progressing along its EU accession plan in parallel.