Recent economic crises have disproportionately impacted the least advantaged in society. As Europe approaches the upcoming European Parliament elections in 2024, there are renewed concerns about an erosion of trust in democratic institutions in Europe. This policy brief looks back to the Great Recession in 2008, which led to a decline in trust and an increase in support for populist parties. Contrary to optimistic assessments, it shows that the apparent rebound of political trust at the country level masks heterogenous developments within European societies. Disadvantaged groups, particularly those with lower income and education levels, experienced a more pronounced drop in trust in the European Parliament in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Alarmingly, those groups’ trust levels have not bounced back to pre-crisis levels yet. To avoid that this gap in political trust widens even further, EU policymakers need to focus more on targeted support measures to cushion the blow of recent crises on already disadvantaged groups.

1. Introduction

In almost exactly a year, EU voters will be heading to the polls to elect a new European Parliament. Looking back, this parliamentary term has been characterized by major economic disruptions, including a sharp recession induced by an unprecedented public health crisis as well as an energy and cost-of-living crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It is now indisputable that these crises have hit disadvantaged groups disproportionately. Against this backdrop, policymakers warned that if the EU were to “fail to shield Europeans from the tsunami of staggering living costs, it risks sweeping away their trust in […] democratic institutions."

More than a decade ago, the Great Recession in 2008 provoked a similar sense of agonizing rethink in Europe. Research provided ample evidence that the Great Recession and the subsequent Eurozone crisis led to a steep decline in trust in EU institutions in Europe, with the aftermath marked by increasing electoral support for populist parties in several EU countries. Nevertheless, the soul-searching abated in the following years, as European economies returned to their growth paths and public opinion surveys indicated a slow but steady recovery in average political trust levels. The decline in trust seemed to have been a temporary phenomenon.

This policy brief suggests that this assessment was and is overly optimistic. Based on an examination of political trust trends between and within EU member states, it shows that the apparent rebound of political trust in countries hit hardest by the Eurozone crisis masks heterogenous developments among different socio-economic groups. The Great Recession had a more profound impact on trust among disadvantaged individuals, exacerbating the political divide between haves and have-nots. Alarmingly, not everyone’s levels of trust have bounced back to pre-recession levels. Those with lower levels of income and education have remained less trustful of the European Parliament compared to the pre-crisis period.

Regaining the trust of the least advantaged in society is going to be a complicated task for EU policymakers. This is aggravated by the serious risk that the distributional effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis are widening the gap in degrees of political trust even more. Once again, more vulnerable socio-economic groups may well feel left behind by the EU. Taking stock of the economic and political consequences of the Great Recession and the Eurozone crisis, policymakers in the EU must cushion the blow of recent crises on low-income households to avoid further loss of political trust among already disadvantaged social groups.

2. Why does political trust matter?

Trust in political institutions is an essential pre-condition for the well-functioning and stability of any democracy. Citizens who trust in the effectiveness and responsiveness of their institutions are more likely to support the implementation of policies although they may not benefit from them personally. Accordingly, trust in political institutions fosters policy and law compliance. Hence, political trust is regarded as crucial for the legitimacy of democratic institutions and their daily work, particularly in times of crisis, when unpopular political decisions might well be unavoidable.

Citizens hold their political institutions accountable for producing outcomes that align with their needs and expectations. In this context, the provision of economic security and decent living conditions is a key task of democratic institutions. Accordingly, research has shown that a visible and profound deterioration in macroeconomic performance drives down citizens’ confidence that political institutions are capable of and committed to fulfilling their responsibilities.

Economic downturns affect everyone – but some groups are likely to suffer more. During times of crises, the risk is that existing social inequalities are reinforced. This is because disadvantaged groups lack the financial means to buffer the impact of economic recessions and tend to be more exposed to changes in the labor market driven by the crisis. Consequently, those groups are likely to perceive the adequacy or indeed suitability of crisis measures very differently than the more privileged segments of society. In the worst case, this leads to diverging assessments of trust among such groups.

A widening gap in trust in democratic institutions could undermine political and social cohesion within Europe. People who distrust the democratic process are likely to feel alienated from the political sphere since they think the system is not delivering for them. So, they tend to abstain from voting, or worse, turn towards populist and extremist political alternatives. Accordingly, researchers have identified a strong association between rising mistrust of European institutions and sharply increasing shares of the vote for Eurosceptic parties in several member states post-2008. Moreover, there is a serious risk of deepening polarization and weaker social cohesion if the gap in trust levels between poorer and wealthier citizens widens. As such, a loss of support for the political system within a significant segment of society would have significant broader consequences for European democracies, and not just in the context of the upcoming European Parliament elections.

3. Trends in political trust between and within EU member states

Data from the European Social Survey (ESS) yield three important findings related to political trust across EU member states. First, there are baseline differences in political trust between EU countries. These differences are more pronounced when it comes to trust in national parliaments, whereas there is less variation as regards the European Parliament. Second, the Great Recession has coincided with a decline in political trust across the EU. However, this decline has been steeper in Southern European countries which have been hit hardest by the crisis. Crucially, average trust levels have gradually recovered in those countries in recent years. Third, those with lower incomes and lower levels of education are persistently less trustful than better-off individuals. Since 2008, this gap has widened. Alarmingly, trust among less advantaged groups has not yet recovered to the same extent as that among high-earning individuals and university graduates.

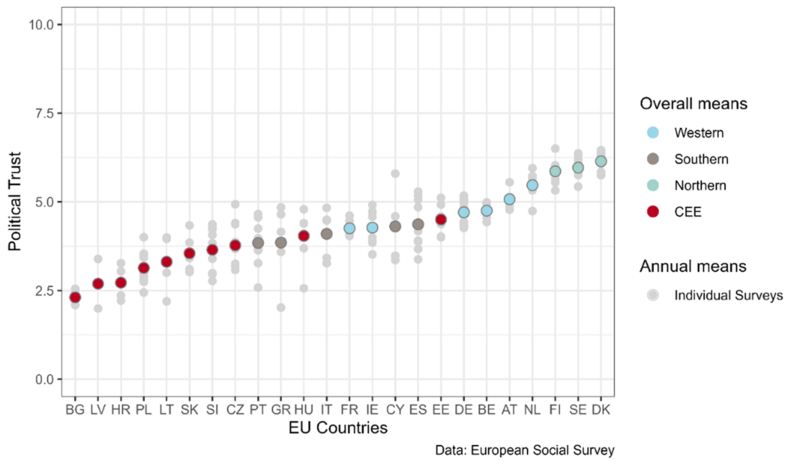

3.1 Political trust differs across member states

Descriptive evidence from the ESS reveals that levels of trust in national parliaments vary significantly across EU countries (see figure 1). However, there is a clear regional pattern: Northern European countries such as Denmark, Finland and Sweden show high and relatively stable levels of trust in their national parliament. They are followed by Western European countries such as the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, and Germany. In contrast to these higher-income EU countries, the data indicates low levels and high volatility of trust in national parliaments in most Central and Eastern European (CEE) and Southern European countries.

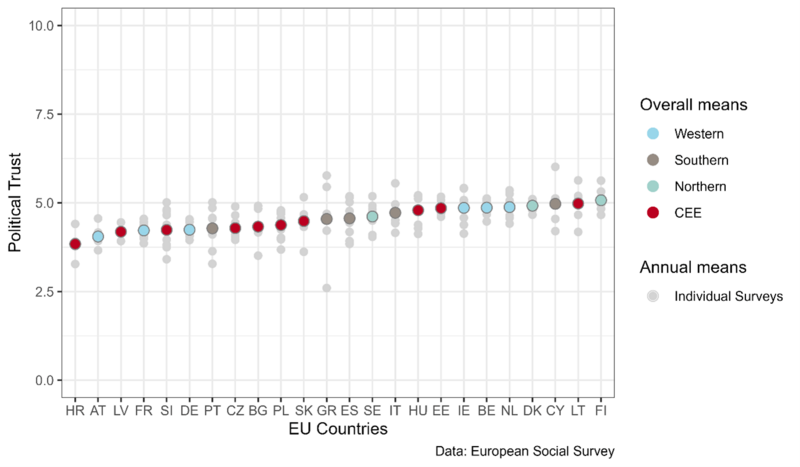

Figure 1: Trust in the national parliament across EU countries, 2002-2020

In comparison, there is considerably less variation in trust in the European Parliament across member states (see figure 2). Strikingly, the European Parliament is on average more trusted than the national parliament in CEE countries. In sharp contrast, those countries with the highest average levels of trust in their national parliament – in Northern and Western Europe - report comparatively lower trust in the European Parliament. It is important to note that Southern European countries such as Greece, Cyprus, and Portugal display greater volatility in average trust levels over the time span. This is likely to reflect the pronounced impact of the Eurozone crisis on these countries.

Figure 2: Trust in the European Parliament across EU countries, 2002-2020

3.2 The Great Recession and political trust

When the global economic and financial crisis hit the EU in 2008, its impact varied significantly between Member States. While most Northern, Western and CEE member states experienced steep but comparatively short-lived recessions, several Southern European countries succumbed to the subsequent sovereign debt crisis, returning to growth paths only in 2014. Accordingly, countries such as Spain, Greece, Cyprus, and Portugal faced a steeper and longer-lasting surge in unemployment than other member states, seeing jobless rates only starting to go down in 2013. Furthermore, these countries had to endure severe austerity measures imposed by the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to consolidate sovereign debt and implement structural reforms.

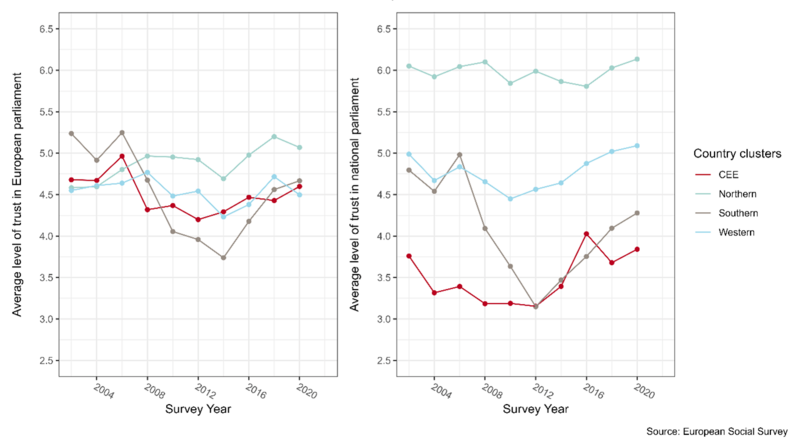

The steepest decline in political trust during the last two decades coincided with the Great Recession, but the decrease has been very asymmetric across Europe. What we can see is that the heterogeneous economic impact of the crisis is reflected in the trends in trust in European and national parliaments (see figure 3). Whereas average trust levels remained relatively stable in Northern and Western European countries and only declined temporarily in CEE, Southern Europe experienced a sharp decline. As such, average trust levels in the national parliament in Southern Europe decreased by more than one-third from 2008 to 2012. The drop in trust in the European Parliament in Southern European countries has been similar in size but was also prolonged until 2014. The austerity programs during the Eurozone crisis may well have triggered feelings of distrust towards EU institutions, as people partially blamed them for the protracted crisis.

Figure 3: Trends in political trust across country clusters, 2002-2020

There has been a notable if gradual recovery in average trust levels in national and European parliaments during the post-crisis period. Accordingly, average levels of political trust in Southern European countries have constantly risen since the end of the Eurozone crisis. Generally, all European regions seem to have experienced a period of increasing trust until 2018. In this light, it is unsurprising that warnings of a trust crisis in Europe have been muted.

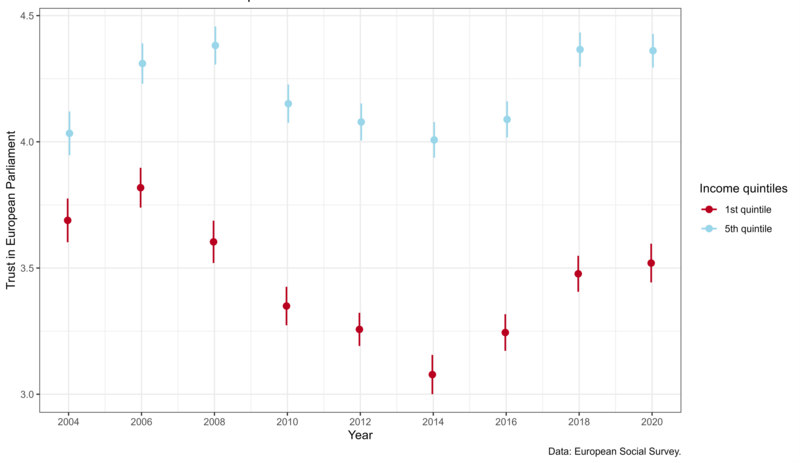

3.3 Trends in political trust among the most disadvantaged

Whereas political trust has seemingly recovered on average, this is not the case for everyone. In fact, the findings indicate that those at the lower end of the income distribution are persistently more distrustful towards the European Parliament than those at the upper end of the spectrum (see figure 4). This difference in trust substantially increased over the course of the Great Recession and the consequent Eurozone crisis, when low-income households in almost all EU countries were disproportionately affected by income losses. Alarmingly, this trust gap remains above its pre-crisis level even now. This is due to the slow recovery of trust in the European Parliament among low-income citizens. In contrast, those on the highest incomes reached pre-crisis trust levels in 2018.

Figure 4: Predicted values of trust in European Parliament by income quintiles, 2004-2020

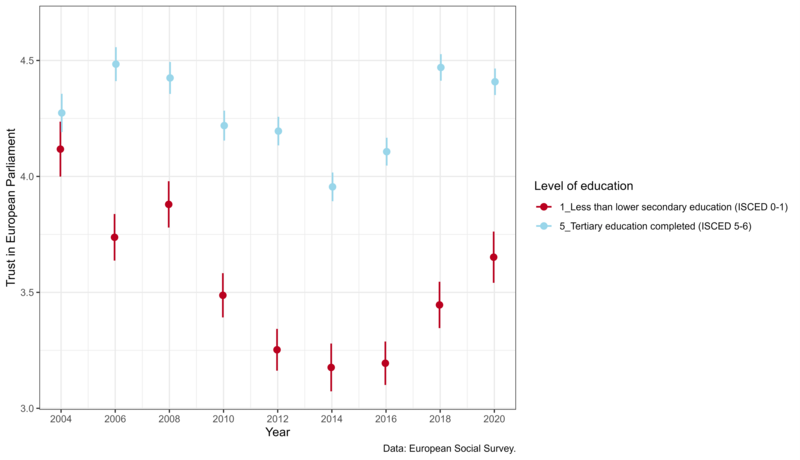

The recovery in political trust among people with lower levels of education lags behind compared to highly educated individuals. While educational attainment seems to have played a negligible role regarding trust in the European Parliament in 2004, this has clearly changed. People with lower level than secondary education show consistently lower levels of trust in the European Parliament than those holding a university degree (see figure 5). While both educational groups show a substantive decline in trust from 2008 to 2014, the drop has been more pronounced among those with lower levels of education. This reflects the concentration of employment losses among low-skilled workers during the Great Recession. As with trust among income groups, the enhanced gap among educational groups did not drop to its pre-crisis level, suggesting longer-lasting damage to trust in the European Parliament among the least advantaged in society.

Figure 5: Predicted values of trust in European Parliament by levels of education, 2004-2020

4. Outlook: The distributional impact of recent economic crises

The finding that political trust among the most disadvantaged has not recovered fully from the Great Recession should be a warning signal to policymakers given more recent economic havoc. The COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing cost-of-living crisis have affected lower social strata disproportionately. This distributional impact will almost certainly reinforce current social inequalities and is likely to make the persistent political trust gap wider still.

4.1 The COVID-19 pandemic

The pandemic left the most disadvantaged even further behind. It delivered a profound external shock that affected all countries within the European Union simultaneously. In contrast to previous crises, the EU was quick to implement a decisive common response. The design and implementation of NextGenerationEU played a crucial role in mitigating the adverse economic impact in fiscally constrained EU countries, as policymakers recognized that substantial divergence in economic performance would ultimately be detrimental to all Member States. This unprecedented policy reaction helped to contain the economic impact of the pandemic. However, it did not prevent the crisis from hitting vulnerable groups especially hard.

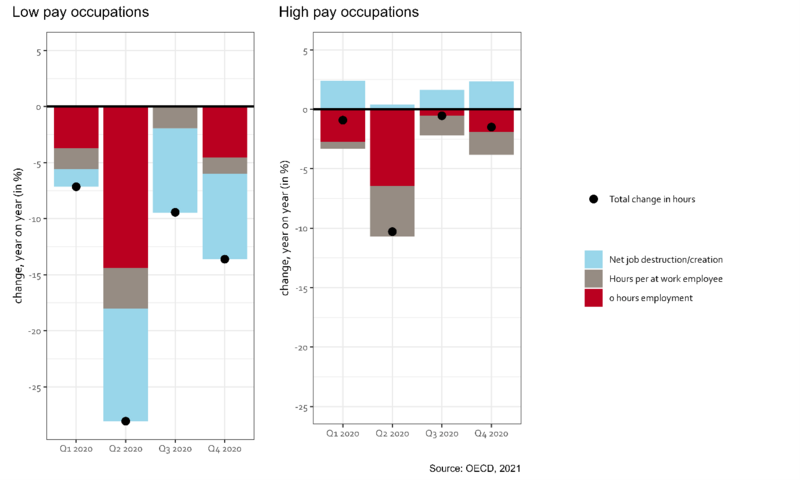

COVID-19 intensified inequalities in the labor market. As such, workers in low-paying occupations have been particularly vulnerable to income and job loss during the pandemic. Figure 6 illustrates the steeper decline in total hours worked among low-paid workers compared to their higher-paid counterparts. NB: a substantial share of the reduced hours among low-income workers was due to job destruction, whereas net job creation remained positive for higher-paid occupations throughout 2020. This is likely the result of a higher proportion of low-paid workers on temporary contracts. Furthermore, low-income workers are over-represented in sectors particularly affected by the pandemic (e.g., tourism, gastronomy, transport, or retail). This is reflected by research estimating that around three-quarters of those in jobs in the highest-paying quintile can adjust through telework, whereas only 3% among those in the lowest income quintile have the possibility to work remotely.

Figure 6: Trends in hours worked among high and low paying occupations during 2020, OECD countries

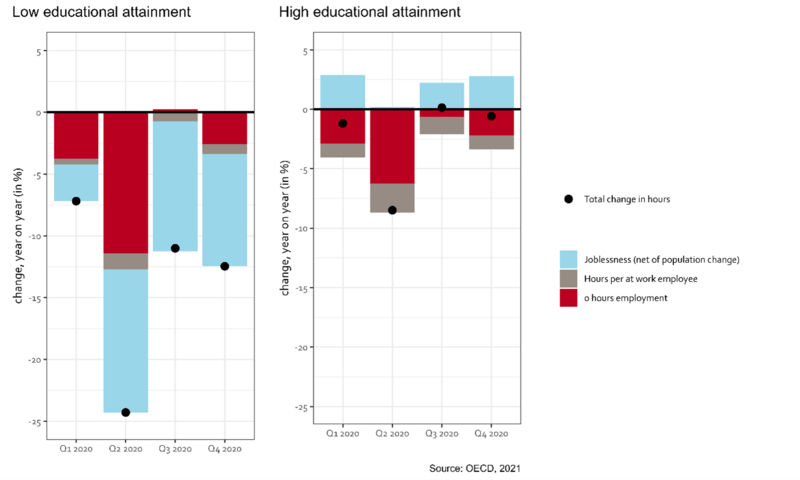

Similarly, workers with lower levels of education have been hit harder by the pandemic than more highly qualified workers. The contraction of total hours worked was more pronounced among less educated workers, whose average hours went down by up to a quarter in Q2 2020 (see figure 7). This was more than double the rate compared to workers with higher levels of education. Notably, about half of the drop in their hours came through joblessness. Alarmingly, this job destruction proved to be persistent in the second half of 2020, while highly educated individuals were able to return to full-time work from reduced hours. Even at the beginning of 2022, the employment rate among the less educated remained below its pre-crisis level in many EU countries.

Figure 7: Trends in hours worked among lower and higher educational groups during 2020, OECD countries

4.2 The cost-of-living crisis

In 2022, Europe faced the highest inflation in half a century, confronting many EU member states with double-digit inflation rates. While inflation across Europe started to decrease at the end of 2021, it is expected that Euro area inflation will stay well above the European Central Bank’s target (“close to but not exceeding 2%”) for the foreseeable future. Accordingly, Euro area annual inflation is expected to be 6.1% in May 2023. Persistently elevated price levels have exacerbated financial pressures on disadvantaged socio-economic groups already hit hardest by the pandemic-induced recession.

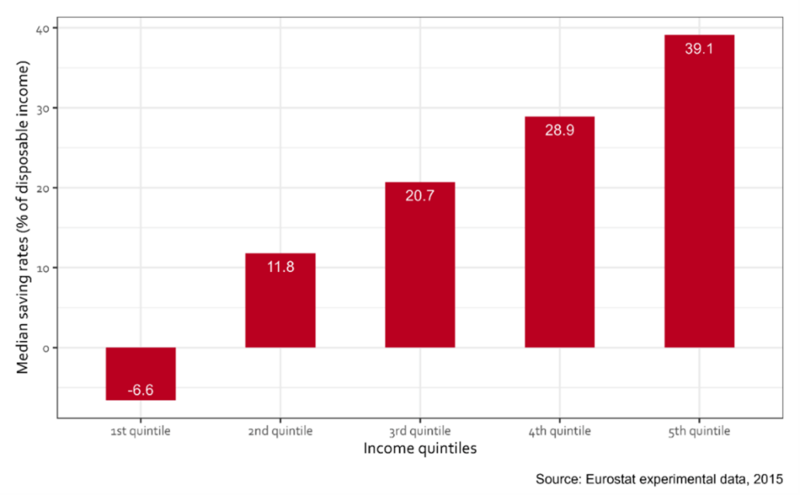

Figure 8: Median saving rates by income quintiles

High inflation rates come with important distributional implications. While all citizens can observe the impact of higher inflation on their weekly grocery bills, not everyone is equally prepared or able to cope with sharp increases in their cost-of-living. While households at the upper end of the income distribution can postpone consumption or make use of their savings, low-income household have fewer financial assets and tend to spend most of their disposable income outright. For example, those in the highest income quintile save almost 40% of their income, whereas households in the lowest income quintile effectively experience negative savings (see figure 8).

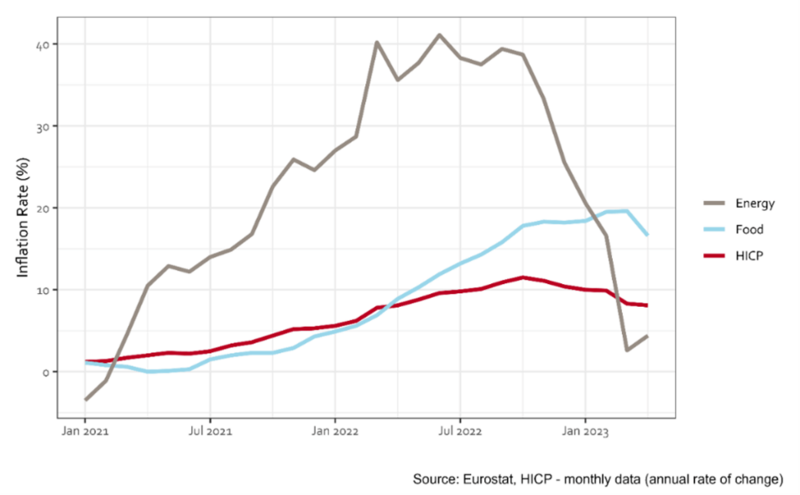

Figure 9: Inflation in the European Union, 2021-2023

Moreover, varying consumption patterns across income groups lead to differences in effective inflation rates between high- and low-income households. Low-income households spend far more relatively on necessities such as food, electricity, gas, and heating. The rise in headline inflation has been significantly driven precisely by the spike in prices for energy and food (see figure 9) - a clear indication of the disproportionate impact on low-income households in Europe.

5. Summary and Implications

The state of political trust in the EU might be worse than we think. In view of the recovery of average levels of political trust across EU member states since the Great Recession and the concomitant Eurozone crisis, the impression that those previous warnings of a “trust crisis” in Europe have been exaggerated. However, while it is true that trust in those countries that saw its steepest decline during the Great Recession has partially recovered on average, the trust gap between lower and higher social strata has not closed. In fact, this political trust gap had widened during the crisis, not only in Southern Europe, but rather across the whole EU.

History might repeat itself. Given the highly unequal impact of the pandemic-induced recession and the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, slowly increasing trust among those on lower incomes and/or with lower educational attainment levels might be stretched once again. Any divergence in trust in central EU institutions such as the European Parliament poses an imminent threat to their legitimacy. Citizens may shun political participation or, even worse, be attracted by the claims of populist and anti-democratic parties.

European policymakers need to make good their promise of leaving no one behind. To prevent long-lasting loss of trust by those hit hardest by the impact of recent crises, policymakers need to focus more on targeted support measures to cushion their effects on the already-disadvantaged. EU institutions have learnt from experiences with austerity policies during the Great Recession and instead implemented swift pan-European measures to avoid vast economic divergences between countries. However, those measures have only partly been able to shield the least advantaged in society from economic hardship. National governments and EU institutions should aim to devise a more effective policy approach to support those at the bottom of the social ladder for maintaining social and political cohesion within Europe.