Despite a broad consensus in the EU on the necessity of enlargement, it is far from a done deal. Especially the financial implications a Ukraine accession pose uncertainties. In our policy paper, Johannes Lindner, Thu Nguyen and Romy Hansum show that the next enlargement round would have less of an impact on the EU budget than is generally assumed. This is largely because the EU’s multiannual financial framework (MFF) has inherent adaptation mechanisms to mitigate significant fluctuations. At the same time, we stress that is impossible to predict precisely what the EU’s MFF, under which accession will happen, will look like as the rules and allocations are subject to political negotiations. Lastly, enlargement is not the only issue adding pressure on the EU budget in a Union that faces huge challenges.

Introduction

On 8 November 2023, the European Commission recommended the opening of accession negotiations with Ukraine and Moldova. At the summit on 14/15 December 2023, the European Council is expected to decide whether to follow this recommendation or not. The accession of Ukraine poses challenges as it is not only a big and poor country but at war. Despite a broad consensus across member states on the necessity of enlargement for geopolitical and security reasons, it is far from a done deal. And support of citizens is equally far from certain posing a possible source of backlash against new members, especially the more costly and financially detrimental enlargement is perceived to be.

Discussions on the EU’s “absorption capacity” and the necessary reforms to prepare for enlargement, both institutionally and policy-wise, are in full gear. In particular, the financial implications of enlargement, and specifically of Ukraine‘s accession, have emerged at the heart of this debate. The accession of a number of poorer member states (and, with Ukraine, a populous one bigger than Poland) will inevitably impact the distribution of funding, in particular within the EU’s common agricultural policy (CAP) and cohesion policy. Specifically, there is the claim of an EU internal study that Ukrainian accession would cost the EU an extra 186 billion Euros over seven years, which would be greater than the EU’s annual budget, and turn a significant number of net beneficiaries into net contributors.

We show that such claims are unfounded for two reasons. First, the EU’s multiannual financial framework (MFF) has inherent adaptation mechanisms to mitigate significant fluctuation in the amounts of funds received by individual member states, including maximum caps on national allocations. According to our calculations, in a hypothetical scenario applying the data and budgetary rules of 2021, no member state would turn from net beneficiary to net contributor if Ukraine joined. The accession of Ukraine, Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Albania, and Serbia would result in total annual additional spending of about 19 billion Euros, i.e. a bit more than 10% of the current budget which would still lie under the EU’s current own resource ceiling of 1.40 percent of EU GNI.

Second, it is impossible to predict what the MFF, under which accession will happen, will look like as the rules and allocations are subject to political negotiations. In the past, during such negotiations, bespoke arrangements were always found, which took into account the distributive interests of both incumbent and future member states, even though more often than not bargaining power was clearly tilted in favour of the former. At the same time, these marginal adjustments happened within the existing budget without any fundamental alterations.

Moreover, this time, enlargement is not the only issue adding pressure on the EU budget. There is growing demand on EU funding in areas such as energy and decarbonisation, digital and research, and defence and security, which will be run into a cliff in 2026 when the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) expires. At the same time, the debt issued under the NextGenerationEU (NGEU) programme will have to start being repaid as of 2028, with interest payments already in train. It is fair to assume that, in the next MFF negotiations, the key method of settling conflicts, namely through incremental adjustments, will face greater challenges than in previous rounds.

Against this background, this policy paper has two objectives: First, in the context of the European Council meeting, we aim to inform the debate surrounding the financial implications of enlargement. Second, we argue that the next MFF will come under substantial pressure, even without enlargement. The upcoming negotiations should therefore not be dominated by talk of the costs and benefits for old and new members. Instead, what is needed is a fundamental rethink of the size, structure and priorities of EU fiscal policy if it is to cope with the demands of a bigger Union facing huge challenges.

An inherent ability of the MFF to adapt to enlargement

The MFF has general adaptation mechanisms to mitigate significant fluctuation in the funding amounts received by individual member states which are negotiated and agreed upon for each MFF period. The Common Provisions Regulation (CPR) hence stipulates caps for cohesion policy funds under the 2021-2027 MFF, setting a cap on the amount a member state can receive equal to a fixed percentage of their GDP. The exact percentage differs according to each country’s economic strength, but no member state can receive more than 2.3% of their GDP in cohesion policy funds. Equally, national allocations may not exceed 107% of what the member state has received in the previous programming period. The CPR also provides for a 24% cap on cuts in cohesion policy funds for current beneficiaries, meaning that national allocations under the 2021-2027 period cannot be less than 76% of what member states have received in the previous programming period. So, even in the case of accession by several poorer countries, there is a cap on both how much new member states can receive and how much current member states, even with the new members, can lose on the previous period. In addition, as cohesion policy funds are allocated based on regions’ level of GNI per capita in relation to the EU average, the overall costs of regional funds may also be reduced as some regions will lose their current eligibility status once the EU’s overall average is reduced through the accession of poorer countries. Similarly, the accession of poorer countries will reduce average GNI per capita in the EU, affecting the number of member states eligible for Cohesion Fund disbursements, i.e. those whose GNI is less than 90% of the EU average.

Moreover, the EU has adaptation mechanisms to deal with the financial implications of enlargement specifically. During the last enlargement round, the new member states did not immediately receive full amounts of direct payments under the EU’s common agricultural policy (CAP). Rather, there was a phase-in period, during which they received only 40% of the level of direct payments allocated to the incumbents, rising subsequently by 10% every year. This phase-in mitigates the financial impact of enlargement by prolonging it. At the same time, candidate countries already receive financial assistance to implement reforms before accession under the EU’s Instrument for Pre-Accession assistance (IPA). For the period 2021-2027, the IPA‘s financial envelope was 14.2 billion Euros, with Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iceland, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey as beneficiaries. Once the candidate countries become EU member states, there will be a netting out effect, as IPA payments will end.

Financial implications of the next enlargement

While the financial implications per se may not determine the decision on the next enlargement, since this is above all driven by geostrategic and security concerns, they will influence it. When it comes to budgetary impact, a distinction can be made between the accession of Ukraine on the one hand and that of the Western Balkan countries and Moldova on the other. The latter group‘s entry has less budgetary relevance due to their smaller economic and demographic size via-à-vis Ukraine. Ukraine has by far the biggest population of the candidate countries and a large agricultural sector with very fertile soil. Assuming it had been an EU member at the start of the current MFF in 2021, its population would have represented nine percent of an enlarged EU, and its utilised agricultural area would have been larger than that of Germany and Poland combined. At the same time, its GDP would have accounted for just 1%. The war obviously poses further challenges. Next to the uncertainties surrounding how it progresses when it comes to timeline, damage and outcome – including contested borders and security concerns both pre- and postaccession –, the country will also require special financial assistance for development and reconstruction. Given the EU’s international commitments and geopolitical interests, a large part of these costs will arise irrespective of Ukrainian membership.

Speculation about the potential financial impact of the Ukraine accession on the EU budget abounds, including over which current member states will turn from net beneficiary to net contributor. But any negative net balance for the EU budget must be balanced against the economic benefits that come with a larger internal market. Crucially, any calculation of the

financial impact of enlargement can only be hypothetical. It is difficult to predict how the specific MFF under which enlargement will happen will turn out as it may well reflect the special circumstances of the entry of new members. During the 2004 enlargement round, the Agenda 2000, which included the Financial Perspective 2000-2006, followed a modular approach, which allowed for the entry of the eight new member states and the switch from pre-accession payments to the inclusion within the MFF during the cycle. In the negotiations, net contributor states were by and large successful in preventing an increase in cohesion policy spending and the overall size of the budget, while incumbent net beneficiaries were able to prevent a too severe loss in what they received.

The MFF‘s political nature does not prevent us making estimates as to the possible financial implications of enlargement by relying on the current MFF 2021-2021 and making use of a range of assumptions and specifications. On the contrary, it is important to start talks on the budget early and constructively on the basis of scenarios, as long as there is an understanding that any result will be heavily influenced by the assumptions underlying the calculations. In the following, we make a first step in contributing to that discussion by providing an estimate as to what would happen if the current candidate countries were all to have become full EU members under the current MFF 2021-2027.

Assumptions and approach

For the purposes of our calculations, we assume a hypothetical scenario in which all candidate countries are full EU members in 2021, i.e., from the start of the current MFF. For both the new and current member states, the economy and population data of 2021 serve as the basis. After the escalation of the war in Ukraine in February 2022 the availability of data has become less reliable. Compared to 2020, data from 2021 also appears less heavily biased by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Our calculations follow the rules and budget allocations of the regular MFF and spending programmes for the 2021-2027 period, while excluding positions outside the regular budget, such as NGEU. In the same vein, the calculations do not consider current and future spending on reconstruction or military aid for Ukraine. For simplicity‘s sake, we determine the expenditures as commitments without any phase-in. This is, admittedly, a stark assumption as a phase-in period would reduce the overall result, especially for the CAP to which it was applied during the 2004 accession round as we have seen.

For current member states, national revenues and allocations are calculated as an average of the 2021 and 2022 EU budget. For new member states, revenues include traditional own resources (projected based on the extra-EU import share and traditional own revenues (TOR) share of current member states) and contributions based on VAT (calculated as uniform call rate based on 50 percent of GDP) and on GNI (calculated as GDP contributions to cover the spending after all other revenues and current country rebates are deducted).

Expenditures for new member states encompass primarily cohesion policy spending (capped at 2.3% of GDP) and CAP spending, including direct payments and rural developments (projected based on CAP allocations per hectare of utilised agricultural area (UAA) and GDP per capita of current member states), as well as spending on market measures (average of CAP allocations per UAA in post-2004 member states) and fishery funds (average of CAP allocations per capita in maritime member states). Except for Heading 1 competitiveness (projected based on GDP per capita and allocations 2021 and 2022 of current member states) and Heading 6 neighbourhood (not increased), all other MFF headings, for which no clear attribution to one specific economic variable is evident, are calculated as average allocation per capita in 2021 and 2022.

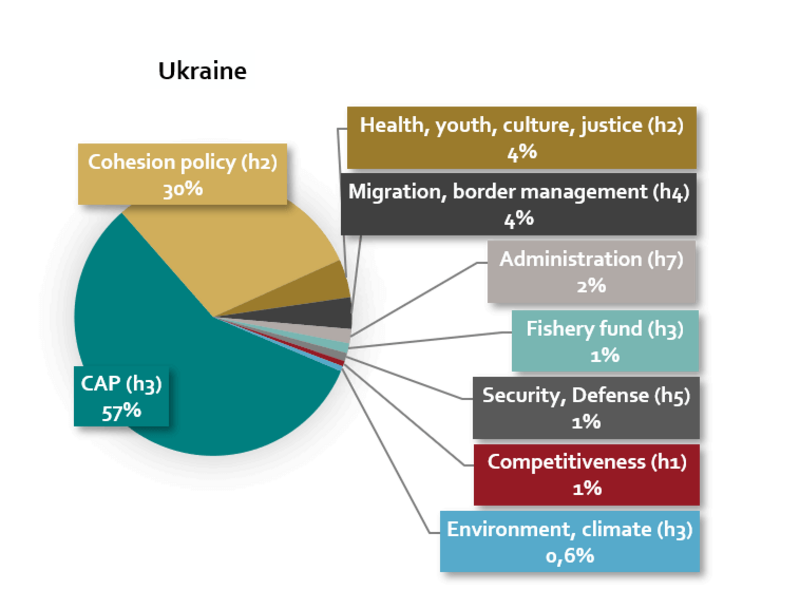

Financial implications of the accession of Ukraine

In a hypothetical scenario in which Ukraine becomes a full member by applying the data and MFF rules in 2021 and under the assumptions described above, the annual additional spending for the EU under a Ukrainian accession would amount to 13.2 billion Euros. As shown in Figure 1, almost 90% of this sum would be allocated through CAP (as no phase-in is applied) with 7.6 billion Euros (57% of the additional expenditure) and cohesion policy with 4 billion Euros (30% of the additional expenditure).

Figure 1: Composition of additional spending for Ukraine as new EU member state

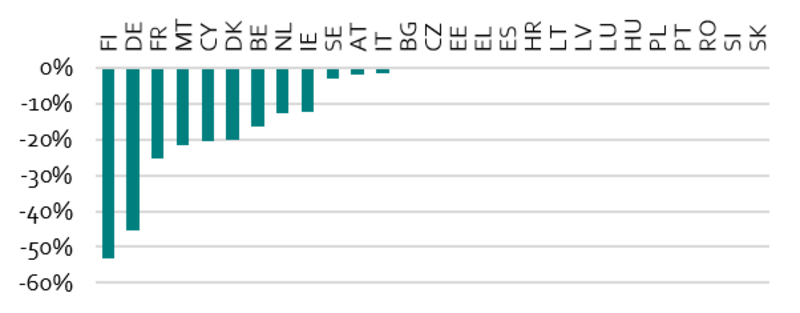

In this context, it is worth zooming into the allocation of the cohesion policy funds to demonstrate how the adaptation mechanisms inherent in the MFF function. In case of a Ukraine accession, the total seven-year funding through Cohesion Fund, ESF+ and ERDF for current member states would be reduced by 13.6 billion Euros – but only if no threshold for a maximum reduction is applied and no regions are downgraded. Figure 2 shows that allocations for Finland, Germany, France, Malta, Cyprus, Denmark, Belgium, Netherlands, Ireland, Sweden, Austria and Italy would be reduced. The reductions for Finland, Germany and France would, however, exceed the cap of 24% which member states can lose at maximum in cohesion policy funds 2021-2027 as compared to 2014-2020. This would thus be an example where the adaptation mechanisms of the MFF would take hold.

Figure 2: Changes in ESF+/ERDF/Cohesion Fund allocations with Ukraine as new EU member state if no thresholds are applied

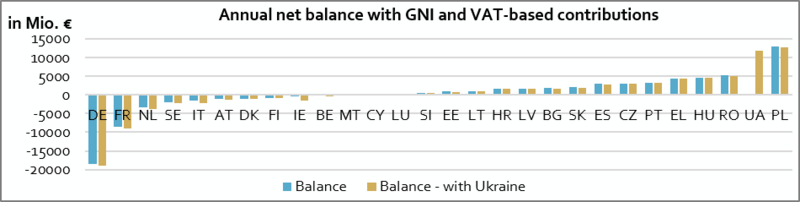

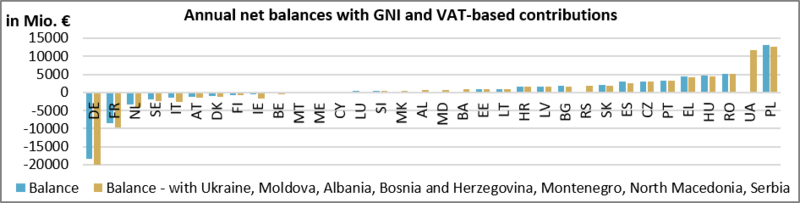

New member states not only receive EU funding but also contribute to the EU budget. Taking into account national GDP and VAT contributions as well as all expenditures except administration, the annual net balance of Ukraine would be -11.4 billion Euros, meaning that Ukraine would receive 11.4 billion Euros more from the EU budget than it pays in. To offset the negative net balance of Ukraine, national GNI contributions to the EU budget of current member states would have to be adjusted. Figure 3 shows the adjusted net balances once the additional spending for Ukraine is included in the EU budget (administration excluded in the expenditure). No current member state would change from being net recipient to being net contributor in case of a Ukraine accession.

Figure 3: Annual net balances with Ukraine as new EU member state

Financial implications of the accession of the Western Balkan countries and Moldova

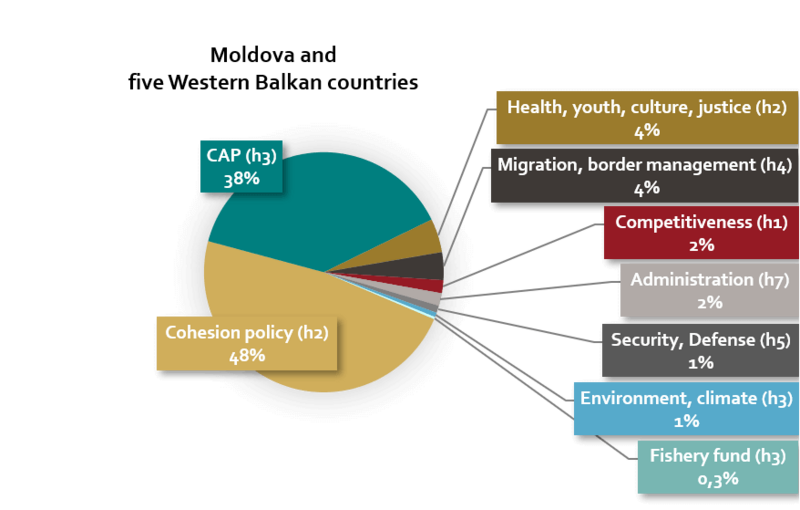

If Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Albania, and Serbia became full members on the basis of the data and MFF rules pertaining in 2021, under the assumptions described above, the annual additional spending for the EU would in total amount to 5.8 billion Euros for them. Unlike for Ukraine and as shown in Figure 4, cohesion policy would be the largest budgetary position at 48% of the additional expenditure, while CAP would play a lesser role.

Figure 4: Composition of additional spending for Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Albania and Serbia as new member states

Figure 5 shows the adjusted net balances once the additional spending for Ukraine, the five Western Balkan countries and Moldova is included in the EU budget (administration excluded in the expenditure). Again, in this scenario no current member state would shift from being net recipient to net contributor.

Figure 5: Annual net balances with Ukraine, Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Albania and Serbia as new member states

Overall, the accession of Ukraine, Moldova and the Western Balkan countries would lead to total annual additional spending for the EU of 19 billion Euros. Keeping the annual expenditures for all existing member states and adding the additional expenditure for the accession countries, this would amount to an overall annual EU budget of 194 billion Euros (175 billion Euros in EU budget, calculated as an average of 2021 and 2022 plus 19 billion Euros extra for the new member states), or 1.3% of the EU’s and accession countries’ combined GDP. This would still be within the EU’s own resources ceiling of 1.40% of EU GNI, i.e. the maximum level of resources that can be called from member states, for the 2021- 2027 period.

Total additional EU spending: NGEU repayment and Ukraine reconstruction

However, the accession of new member states will not be the only additional cost factor in the next MFF or the one after if enlargement were delayed until the MFF for the period of 2035-2041. The costs of enlargement cannot be considered in isolation. Starting with the new MFF, the EU will have to include provisions on repaying the debt issued under the NGEU, which will add significant pressure on EU finances. This comes on top of interest payments, which are significantly higher than expected when the programme was set up in 2020 – an issue now being discussed within the mid-term MFF review. By 2058, when the debt will have to be repaid, these interest costs alone could amount to a total of 222 billion Euros. Together with the reimbursement of the non-repayable parts of NGEU that were disbursed to member states in the form of grants, the EU could end up having to spend between 582 and 715 billion Euros over a period of 30 years. At the time of its adoption, the EU increased (up to 2058) the own resources ceiling by 0.6% to 2.0% GNI and also made a commitment to introduce new own resources. The Commission has in the meantime followed up with proposals which the Council has, however, yet to agree upon. If one desregards the question of how these would be repaid and add it to the EU budget, this would mean an annual additional expenditure of between 19.4 and 23.8 billion Euros.

Adding up both the additional spending for Ukraine, Moldova and the five Western Balkan countries and the additional spending required for NGEU repayment, the total EU budget would amount to 1.45% of an enlarged EU’s GDP. This would exceed the own resources ceiling of 1.40% of EU GNI but stay below the temporarily extended 2.00% GNI ceiling.

Moreover, the reconstruction of Ukraine will require considerable financial support from the EU and its member states. Between January 2022 and July 2023, EU countries and institutions have already committed 132 billion Euros of government support, both financially and in-kind transfers, to Ukraine. In autumn 2023, the European Commission proposed a new Ukraine Facility, under which 50 billion Euros would be provided in grants and loans between 2024 and 2027. Estimates foresee that aid for the reconstruction and recovery of Ukraine could amount to another 383 billion Euros over the next decade. At the same time, depending on the severity of war-induced damage and destruction, reconstruction costs could be covered through pre-accession support and, upon membership, expenditure from the EU policies. And eventual increases in Ukraine’s GDP beyond 2021 levels will raise its contributions to the EU budget.

A growing pressure to reform

There is growing pressure in the system to reform the MFF. In the past and in a Union that was largely about market integration (and regulation), the EU budget served a compensation function that had enabled the various steps towards integration to take place. Yet, the Union has evolved and so have the challenges it faces. The Covid-19 pandemic stands for an external shock for which collective responsibility and, with NGEU, a common response was accepted, despite its redistributive character. In a similar manner, the shock of war in Ukraine has led to the re-emergence of defence and security as a priority in all member states. The next MFF 2028-2034 will come under considerable pressure, even in the absence of enlargement. Next to servicing pandemic-related debt, the EU faces a growing demand in areas such as energy and decarbonisation, digital and research, and defence and security, which have created additional pressure on EU funding. With the expiry of the RRF in 2026, member states will at the same time also run into a cliff in their receipt of EU funding in particular for European climate and digital goals. There is thus an inherent pressure for MFF reform, even in the absence of enlargement. This has two implications for the negotiations.

First, a discussion about the size of the budget will be needed. Otherwise, the response to these challenges might come at the expense of delivering true European policies and public goods. Some hopes are being pinned on new own resources for generating further revenues for the Union and potentially loosening the focus of member states on their net balance (the so-called juste retour approach). But the reality is that there has been little progress made on the commitment to introduce new own resources linked to plastics and residual profits from multinationals at European level to off-set the additional spending. These proposals largely stay within the rationale of national contributions. They only alter the distributional key among what member states have to transfer from their national budgets. New own resources in the form of taxes or revenues that are established at European level, such as the Emissions Trading System (ETS) or Cross Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), could move away from national contributions. Yet, under its current disposition, ETS receipts are largely attributed to national budgets and there is high pressure from member states to do the same for any extension of the ETS to new sectors. In the absence of a break-through on truly new own resources, there are thus only two options to off-set the required additional spending at EU level: higher national contributions, or more common European debt, within the legal constraints of the current Treaties.

Second, there will need to be a review of the MFF‘s composition to ensure that its structure reflects the new challenges, which the EU faces. This is inevitably linked to the first question of how a bigger budget can or should be redirected. There has long been a call to redirect EU expenditure away from the two dominant expenditure groups, CAP and cohesion policy, towards projects at a European level, which could generate beneficial effects for all member states by being allocated on the basis of excellence criteria rather than geographical or distributional balance. Industrial policy and innovation funds are examples. The Versailles Summit in March 2022 at the very start of the war in Ukraine made a first comprehensive stab at linking MFF reform to the new challenges that the EU faces.

Here, enlargement can present an opportunity to break decades-old gridlocks on CAP and cohesion policy, while further accentuating pressure for reform. The accession of new and poorer countries, and in particular that of Ukraine, means that in the medium-term economic divergences remain increased in a Union with a lower average GDP. Despite MFF capacity to adjust to enlargement, greater redistribution of funds will go to the Eastern and Southern parts of the Union, thereby reducing the number of incumbent regions and member states benefiting from cohesion policy-related spending. Moreover, Ukraine with its large productive farms alongside very small (subsistence) farms may impact the debate on CAP reform. It provides ammunition to those that question the current focus on smaller (family) farms, predominant in Western Europe, and argue for structural changes to raise economic efficiency and accelerate greening of the agricultural sector. Finally, the relevance of common spending on defense, foreign and security policies, and border controls will only grow even more with enlargement. In other words, enlargement will increase pressure for a root-and-branch review.

Conclusion

The next enlargement round will have financial implications for the EU and its member states but they are less significant than according to some calculations. This is because the MFF has inherent mechanisms to adapt to new members and to prevent excessive losses for incumbent member states. At the same time, the accession of a number of poorer countries will increase medium-term economic divergences in the EU and require an adjustment of the contributions to the EU budget by the incumbent member states to compensate. These additional expenditures add to an already existing pressure on the MFF, rendering its reform increasingly relevant if enlargement is not to come at the expense of European policies and common goods, just when the EU faces increasing supranational challenges requiring European solutions.

It will be important to avoid getting bogged down in rows about budgetary losers and winners within an enlarged EU. Instead, we need a fundamental debate on the size, structure and political priorities of the next MFF to deal with the challenges ahead. Timing will also be vital considering that the negotiations on the MFF 2028-2034 will have to start in 2025, bringing structure to a debate that might otherwise block the enlargement process as well. The European Council will need to recognise this in the form of a roadmap linking enlargement with reform when opening accession negotiations with Ukraine and Moldova.

For this paper, an expert workshop was held in November 2023. We thank participants for their time and insights, as well as other experts and decision-makers from EU institutions and member states that we talked to. We thank in particular Eulalia Rubio und Jörg Haas for their comments and feedback on an earlier draft. The views and opinions expressed in this policy paper are solely those of the authors.