“Young people are at the heart of our policymaking and political priorities. We vow to listen to them, and we want to work together to shape the future of the European Union”, stated European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen during the celebrations of the 2022 European Year of Youth. Nevertheless, young generations today are underrepresented in European institutions and their interests risk being sidelined. For this reason, we advocate the introduction of youth quotas in the European Parliament. These should take the form of legislated candidate quotas. Our aim is to increase the number of young adults elected to match more closely the share of under-35 in Europe. Only in this way can we ensure that the distinct concerns of younger generations are being adequately heard and discussed in the decision-making arena.

For a full text, including the appendix, please download the PDF above.

Introduction

The ongoing demographic change is aggravating the gap between youth participation and youth representation in the European policy-making process, possibly bringing about systematic disadvantages for the future generations of Europeans. The need for increased youth engagement in elections has already been highlighted to some extent by the electoral law reform currently being discussed in the European Parliament, which also advocates for zipped lists or gender quotas to address female underrepresentation. Although the law reform would entail symbolically setting the voting age at 16, national rules would still apply, and as the age to stand as a candidate is 18, the youth underrepresentation issue has not been adequately addressed in the current debate, thus making it necessary to tackle it in a future round of reforms.

Young Europeans have indeed manifested their desire for increased political participation: the latest elections for the European Parliament have recorded an increased turnout of younger generations. Nevertheless, despite these advancements, there is still room for improvement. In light of the aforementioned electoral debate, it is important to ensure that the decision-makers of the future also have a say in European politics right now and do not get marginalised by politicians.

The youth representation gap must be closed

Although extensive research exists on the composition of national parliaments in terms of gender, economic status and ethnicity, the representation of younger cohorts is often overseen as a topic in the literature. Yet, adequately representing what has been defined as a ‘politically excluded majority’ should be regarded as desirable both from a normative standpoint and from a policy perspective.

The underrepresentation of young people within European institutions is a long-standing issue, with young people constituting only an extremely small percentage of European Parliamentarians. In the 2014 election, only 11,4% of the elected MEPs were under 35, which is far from the percentage of under-35 in the European population (18% in 2020). The age of 35 is not random: political behaviour literature defines being young as being under the 35 threshold.

Today, the average age of MEPs is still 50 years old, with national averages varying from 44 to 60. Denmark has the youngest MEP (21-years-old at election), while for other countries, the youngest MEP is at least 30 years old. This evident mismatch between the percentage of under-35 MEPs and Europeans of the same age cohort implies a gap in descriptive representation, with important policy implications.

Descriptive representation is defined as the extent to which a legislator resembles those being represented in relevant characteristics, shared experiences or common interests. This type of representation not only helps all groups be represented more substantively, but also increases the de facto legitimacy of the decisions being taken, as well as the fairness of the decision-making process. At the individual level, descriptive representation empirically increases the willingness of the public to accept policy decisions, enhancing perceived legitimacy. Thus, having better representation of the younger cohorts would not only make them feel more heard by the European legislators, but also more willing to accept their outcomes. Moreover, introducing youth quotas would contribute to promoting values such as respect for democracy and equality, as well as social equity and solidarity between generations, in line with the Union values enshrined in Articles 1a and 2 of the Treaty of Lisbon.

Extensive research on the policy impacts of descriptive representation in the legislature also shows how representation can translate into better legislation on topics relevant for those being (better) represented. For instance, evidence demonstrates how the number of women in the legislature positively affects the policy outcomes that are deemed to be a greater concern for them (e.g. child care provision). This occurs either because politicians become active advocates of issues that are relevant for the represented group (so-called ‘active’ or ‘substantive representation’) or simply because their mere (increased) presence in the bureaucracy enhances the trust among those being represented (‘symbolic representation’). Therefore, although it is not automatic that younger MEPs would advocate issues of greater concern for young Europeans, evidence suggests that descriptive representation is indeed beneficial to those being represented in terms of legislative action. Increasing the share of under-35 MEPs means increasing the extent to which they can be spokespersons for young Europeans and bring their interests to the political agenda, which would in turn encourage young individuals to participate more actively in the political realm.

Finally, closing the gap in youth representation could have several beneficial consequences for the whole European Union. As the literature indicates, the arrangement of political institutions matters for the share of young people in parliaments and influences voting behaviour. Thus, if the younger cohorts are better represented, we can expect even higher turnout in future European elections. Given the greater concern of younger Europeans for climate change-related issues, an increased youth turnout would also contribute to achieving the ‘green’ priorities of the current Presidency of the European Commission.

In conclusion, youth quotas ensure that the European Parliament is socially representative of its citizens and responsive to the demands of young individuals, who would then have equal opportunity to contribute to the decision-making process, fostering democracy and trust in the European institutions.

Higher youth representation entails different policy preferences

As mentioned earlier, increasing youth representation in the European Parliament is crucial not only from a normative point of view but also in terms of policy outcomes. While age is not a characteristic that remains stable across an individual’s life, evidence points to the fact that young people have distinct policy preferences compared to older cohorts, implying that political inclinations can change with age. For example, young Europeans are found to be more supportive of same-sex marriages policy proposals, proving to be less conservative on social issues than their older counterparts.

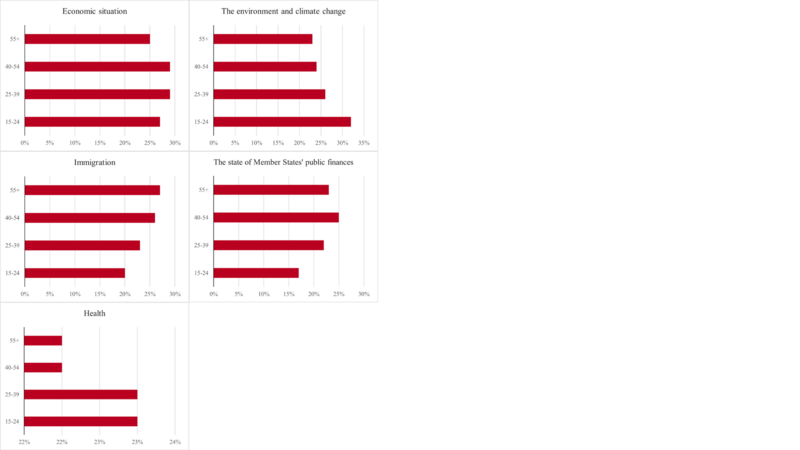

To confirm this, we have looked at the effect of age on citizens’ preferences, taking into account the five most important issues for the EU as identified in the Eurobarometer 95.3, administered between June and July 2021 to 37,214 individuals. When answering the question ‘What do you think are the two most important issues facing the EU at the moment?’, European citizens focused on 1) the economic situation; 2) the environment and climate change; 3) immigration; 4) the state of Member States' public finances; 5) health.

By running a logistic regression of age on each preference, controlling for relevant variables such as gender, income and the educational level, we found a statistically significant effect of age on preferences. For instance, the average probability of choosing the environment and climate change as the most relevant issue decreases with an increase in age (see Appendix). The direction of the effect is alike for preferences regarding the economic situation and health. Conversely, when it comes to the state of Member States' public finances and immigration, older individuals are more likely to regard these as the most important issues. These findings confirm not only that young Europeans have distinct policy preferences, but also that there is a cleavage between young and older generations in terms of political inclinations. This is also noticeable in Figure 1: for instance, among those that consider the environment and climate change as the most relevant issue, the majority is constituted by young people (taking into account the two younger cohorts).

Arguably, some parties have begun to take these different preferences into account to some extent, as demonstrated by the rise of the Green party in recent years. Yet, having more young people in the European Parliament would lead to a substantial and faster shift in policy priorities, given the different perceptions of the urgency of the above-mentioned matters. Therefore, the lack of adequate youth representation matters not only for normative arguments, but also for its important policy implications: underrepresentation implies that the distinct political preferences of young Europeans are not sufficiently being taken into account at the decision-making level.

Fig. 1 Importance of the five most relevant issues (% of respondents by age)

Barriers to youth representation

The implementation of youth quotas within the European Parliament becomes even more pressing when one considers the barriers, both formal and informal, that young politicians encounter when trying to enter the institution. In particular, young cohorts face systematic challenges that make it more difficult for them to run as candidates and be elected, such as national eligibility rules and the hefty costs of campaigning, in addition to informal barriers to youth engagement.

National eligibility rules

The eligibility rule embedded in national electoral systems often hinders the active participation of younger candidates: age limits prevent young people from accessing the European Parliament directly and signal that politics is neither made for nor by young people. 18-year-olds can currently run as candidates in only fourteen out of twenty-seven Member States, while in the remaining thirteen they have to be at least 21, 23, or even 25 in the case of Italy and Greece.

Campaign financing

Although less costly than for general national elections, running for European elections requires significant funding. This represents an evident entry barrier to the political arena for all young politicians who are yet to be included in well-established networks and may struggle to collect the necessary resources. When there are no regulations on funding in place, the likelihood of the election of a newcomer decreases, benefitting the incumbent. Indeed, the great majority of Member States have low or medium limitations to party donations, entailing a systematic disadvantage for newcomers.

Informal barriers

Lastly, there are also informal barriers to youth political participation, such as lack of political literacy and experience, the difficulty of entering well-established networks and the struggle of young elected representatives to reach top positions (currently, the average age of EP committee chairs is 50.9 years).

Overcoming the barriers

Overcoming each of the aforementioned barriers would have beneficial effects on youth representation in the European Parliament.

With regards to strict eligibility rules, allowing younger politicians to be candidates implies giving them a chance to gather the much-needed experience: if all young Europeans were to be eligible at 18, they would ideally have the possibility to run in two European elections by the time they turned 23.

Moreover, aligning candidate eligibility with the age of voter enfranchisement is shown to increase participation and youth turnout, while contributing to overcoming the apathy and disengagement that some younger individuals may feel towards European institutions.

Considering campaign financing efforts, introducing caps and limitations to donations to political parties fosters competitive elections, levelling the playing field for all candidates. Hence, introducing international standards on the financing of political parties and election campaigns is considered desirable.

Lastly, the need for strengthening youth party wings is motivated by the fact that these groups have proven to be valuable organisations to recruit and train young aspiring leaders, equipping them with the expertise they need to enter political institutions at a young age. Strong youth wings can further nudge political parties into embracing youth concerns, thus contributing to achieving the objective of the quotas.

Overall, all these improvements would contribute to eliminating the aforementioned systemic barriers. However, only together with standardised youth quotas will they constitute a holistic and comprehensive way to encourage youth participation and enhance representation.

Legislated candidate quotas as the way forward

The European Parliament has been calling on EU member states to adopt proactive measures to increase the representation of underrepresented groups at the supranational level. One solution to ensure that young people’s interests are adequately promoted in European political fora is the enactment of youth quotas in the European Parliament. These, like other quota regimes, help to address issues of underrepresentation of a specific group, such as the younger generations. Specifically, we recommend that the European Parliament commits to reaching a flexible percentage target of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) under the age of 35 (who have not yet turned 35 on the day of the election) that is reflecting the share of under-35 in the EU population at the time. Furthermore, youth quotas would apply on top of the already existing gender quota specifications, where in place. In fact, it is believed that these two types of quotas can reinforce each other in a positive manner and that their simultaneous enforcement can promote the idea of youth and gender as cross-cutting identities.

Although youth quotas have been adopted by a few countries so far, they have already been implemented in some national parliaments, mainly on the African continent (e.g., Morocco, Rwanda, Tunisia), but also in Asia (e.g., Kyrgyzstan, Sri Lanka) and Europe (e.g., Sweden, Cyprus). The quotas vary according to the age group, the percentage chosen, and to the type adopted. There are three possible types: reserved seats, party quota, or legislated candidate quota. Literature shows that countries utilising reserved seats and legislated youth quotas tend to have higher levels of youth representation than party quotas, when looking at the percentages of young parliamentarians under 40.

In Europe, party youth quotas have been adopted in Sweden and Germany by some national parties. For instance, the German Green Party has set a ‘newcomer quota‘ in several state-level party statutes, with the goal of increasing young people’s representation by limiting incumbency advantages: one out of every three consecutive places on the party’s list must be filled by a candidate who has not served in a state, federal, or European parliament.

The three quota designs, reserved seats, voluntary party quotas, and legislated candidate quotas, have different implications.

1. Reserved seats

Reserved seats fix the number of young MEPs to be elected within the Parliament. This type of quota inevitably achieves the goal of increasing representation; nevertheless, it is the least-used globally as it raises legitimacy concerns. Indeed, given that it is agreed upon that a certain number of seats is assigned to the underrepresented group, young candidates would undergo a less competitive election compared to the other groups’ contestants. Hence, this would advance the idea that anyone would be suitable as long as they fit the age requirement, overall undermining the image of young people in politics. Reserved seats can be found in Kenya, Morocco, Rwanda, Uganda for example.

2. Voluntary party quotas

Voluntary party candidate quotas refer to internal targets set by political parties to include a certain percentage of young politicians as candidates, without it being required by law. They can be enshrined in party rules or informally adopted. However, this quota regime is considered to lead to a gradual change, which will only delay the achievement of the final aim, namely, increasing the representation of European youth at the institutional and decision-making level. Therefore, given the urgency to enhance representation and reach significant results in the early phase of this policy proposal, this type of quota would represent a track that is too slow for accomplishing the goals set. Forms of voluntary party quotas have been implemented in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Cyprus, Germany, Pakistan, Senegal, Sweden, Zimbabwe for example.

3. Legislated candidate quota

Considering the pitfalls of the previously mentioned proposals, the implementation of legislated candidate quotas represents the optimal alternative. This consists in the adoption of a binding form of candidate quota for all parties that intend to run in European Parliament elections. While the latter are largely governed by national electoral laws, our proposed legislated candidate quotas would be mandated, legally embedded within the framework of articles 20, 22 and 223 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), and part of the common EU rules regulating European elections, as prescribed in the Electoral Act of 1976.

Other than the design of the quota regime, there are two factors that should be taken into account to increase the chances of policy success: the rank and order rule and sanctions for non-compliance. With regards to the rank and order rule, which provides the guidelines concerning the placement of candidates on the list and according to winnable seats, it is necessary to consider that MEPs are elected according to national electoral systems. Although for European elections proportional representation (PR) is mandated by EU law, there are three different PR electoral system types that are currently in place in the different European Member States: preferential voting, single transferable voting (STV) and PR with closed lists. Youth quotas should therefore adapt to these different systems. Nevertheless, it is relevant to highlight that a merely symbolic representation in which young candidates are placed at the bottom of electoral lists just to fill in the spots should be avoided. Young candidates ought to be given an actual chance to fight for the seat and be elected. For this, the quota regime should require the presence of a young contestant in the first positions of each party list in the national constituencies where the party foresees to run during European elections. As an example, in preferential voting systems, the rule could establish that among the four choices, at least one must be for an under-35 candidate. This would also allow not to interfere with gender quotas that mandate the same number of preferences for women and men.

Regarding the second factor for success, differently from voluntary party quotas, it would be necessary to include penalties for those parties that do not abide by the standards set by the youth quota regime. Considering the instances in which such quota regimes are in place, it seems feasible to restrict access to public funding for non-compliers, or, in the most severe cases, even reject the party list. Similarly, this also happens when gender quotas are not complied with. In France, for instance, nonconformity with the gender quota regime results in a financial penalty: the public funding provided to parties based on the number of votes they receive in the first round of elections is decreased ‘by a percentage equivalent to three-quarters of the difference between the total number of candidates of each sex, out of the total number of candidates’. Egypt, Peru, Sri Lanka, and Tunisia have already enforced legislated candidate quotas.

Implementation of the proposal

It can be challenging to assess the feasibility of our proposal given the very few instances in which youth quotas have been implemented in the world so far. However, based on these existing examples, they can indeed be introduced in a variety of institutions, both at the subnational and at the national level. As mentioned earlier, in fact, some European countries are already adopting some forms of youth quotas. Nevertheless, since our idea focuses on the European level, specifically on the European Parliament, the comparison with gender quotas becomes handy once again to strengthen the feasibility argument. Indeed, from a purely technical point of view, the two quota regimes find a common ground as they share the same objective, namely the quest for equal participation. Thus, considering that the text on the proposed changes to the European electoral law which includes gender quotas has recently been adopted by the European Parliament plenary, there seems to be no issue in claiming the feasibility of establishing an analogous youth quota regime.

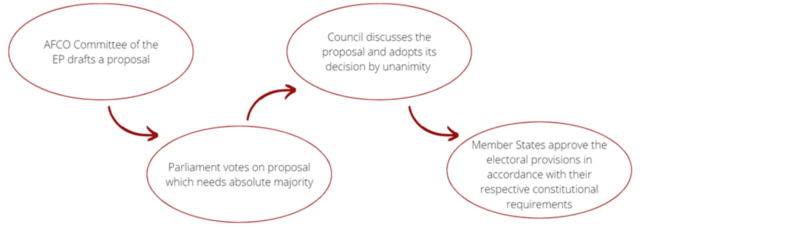

When it comes to the implementation of the proposal, it is worth mentioning that while the European Parliament has no formal right of legislative initiative with the Ordinary Legislative Procedure, the Treaties of the EU grant it such right in specific matters, such as electoral law. Figure 2 illustrates the procedure for changes to the electoral law of the EP. As previously stated, the proposal regarding the reform of the electoral law for the 2024 elections is already ongoing, therefore discussions on introducing youth quotas should take place as part of the next electoral reform, which would eventually lead to their debut in the 2029 elections. For this to be achieved, decision-makers ought to understand the relevance of the policy problem during the evaluation phase of the electoral law after the 2024 elections. Thus, after lobbying for the policy to reach the top of the MEPs’ agendas, the Parliament should initiate an electoral law reform including youth quotas.

Fig. 2 Procedure for changes to the electoral law of the European Parliament

Conclusion

Overall, mirroring the literature on gender quotas, the introduction of youth quotas can be seen as a participatory mechanism that quickly help to reach a more equal and substantive representation of the young population in institutions. It represents an easy way to address the gap in representation as well as promote cultural change. Moreover, the adoption of this quota regime does not prevent the implementation of meritocratic selection, since candidates are still subject to fierce competition to win a seat in the Parliament.

The first step to ensuring that younger generations have a say in European politics is to guarantee they can find a seat at the table. The implementation of youth quotas would firstly lead to more young voices in the Parliament and would eventually engage more young people in politics. In light of their institutional ripple effect, they would lead to a more age-diverse Parliament, better able to represent the various range of concerns that European constituents might have and better prepared to address present and future challenges, bringing benefits to society as a whole.

The authors are the winners of second edition of the futurEU Competition. The students in the competition were given carte blanche to present one visionary reform of the European Union. Their proposal to introduce youth quotas to the European Parliament to increase youth representation triumphed over an array of other interesting ideas. The futurEU Competition focuses on student voices for the EU of tomorrow; for more information read here: https://www.futureu-initiative.org/