The EU Military Assistance Mission in Support of Ukraine (EUMAM UA) is designed to support Ukraine’s army in its fight against Russia’s invasion. A two-year mission envisions training 40,000 Ukrainian soldiers on Western weapons systems and aims to maximise the utility of military assistance provided to Ukraine by its international partners. Can EUMAM UA provide Ukraine with a decisive advantage that wins the war? In this policy brief, Sascha Ostanina argues that EUMAM UA requires a longer mandate for Ukrainian troops to overcome real-life constraints. Consequently, the training mission’s cumulative impact can turn EUMAM UA into one of the key components of Ukraine’s battlefield successes. To increase its cumulative impact, the EU should also standardise the content of EUMAM UA courses and merge EUMAM UA with other EU military aid measures set up for Ukraine.

Introduction

The European Union has taken a further step away from its long-favoured soft power approach to foreign policy. In November 2022, nine months after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the EU launched an EU Military Assistance Mission in Support of Ukraine (EUMAM UA). Of all the EU’s contributions to the Ukrainian war effort thus far, this is perhaps the most hands-on. EUMAM UA is also the first EU training mission (EUTM) set up on home territories, marking a new milestone on its ten-year trek to becoming an independent security actor.

A fully-fledged assessment of EUMAM UA is obviously not yet possible, as the training mission is still ongoing. One year into the mission’s launch, this policy brief assesses how the first half of its mandate has gone. The objective is two-fold: First, to identify the current training mission’s shortcomings that limit its ability to provide a decisive battlefield advantage to Ukraine’s army and to make recommendations on how the training could be adjusted to better benefit Ukraine’s army in the coming stages of war. And second, to analyse the EU’s continuing adjustments to its crisis response mechanisms by arguing that it could accommodate domestic military training missions within its existing portfolio of similar measures. This would further strengthen the EU position as an independent security actor.

The Emergence of EU Training Missions

A format for overseas EU missions and operations emerged in the early 2000s. During the Kosovo war of 1998-1999 it became clear that European military capabilities did not suffice to perform necessary humanitarian relief, peace keeping, and peace enforcement. Instead, the EU had to rely heavily on the United States to trigger NATO intervention in the region. As a response, in December 1999, the EU announced its intention of becoming a more robust and credible security actor. To that end, Europe began increasing its competence in crisis prevention, crisis management, and post-crisis rehabilitation. A combination of civil, police, and military instruments, which could be tailor-made to a specific mission’s objectives, was designed to increase Europe’s ability to respond to international crises in partner countries.

Since 2003, the EU has deployed over 40 civilian and military missions or operations in its neighbourhood: in Africa, the Middle East, the Western Balkans, and Eastern Europe. In 2010, the EU established its first training mission (EUTM) in Somalia, followed by EUTMs in Mali (2013), the Central African Republic (CAR) (2016), and Mozambique (2021). These missions are aimed at providing training support in the anti-terrorism fight and promoting reforms of the security sector and armed forces.

In general, EUTMs have had positive effects on security sectors of the hosting countries and the effectiveness of their armed forces. Still, they have struggled to scale up their impact, mostly due to financial shortages. EUTMs are forced to rely on third parties to provide training equipment, as the EU budget cannot be used for EU overseas operations with a military component. As a result, EUTM Somalia had to employ replica weapons made of wood for training light infantry companies in combat. In the CAR, soldiers arrived at the training facility without weapons or ammunition. These problems were not limited to lethal equipment. In Somalia, trainees lacked uniforms, boots, and water, while living at a training camp, with not enough food or beds.

To offset existing legal constraints on EUTM funding, the EU established an off-budget financial instrument, the European Peace Facility (EPF). The EPF was originally allocated €5.7bn for the period 2021-2027, with the option of adding €3.5bn up to 2027. These funds can be used to procure training equipment for EUTMs trainees, including uniforms, weapons, and ammunition. This could contribute to increasing the EU’s influence in such countries as Somalia and the CAR, and to reducing reliance on military training and equipment provided by Turkey and Russia, on one side, and the US and the UK, on the other.

The EU Military Assistance Mission in Support of Ukraine (EUMAM UA)

Even before Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, Ukraine called upon EUTMs. In October 2021, Ukraine and a few EU member states, particularly Eastern European countries, Sweden, and Finland, lobbied to set-up an EU advisory and training mission for Ukraine. The need was obvious: Since 2014, Ukraine’s armed forces have been fighting Russia-backed separatists in the country’s east. On top of that, Russia was repeatedly amassing its military forces near the Ukrainian border. In early November 2021, Russia’s Defence Ministry left some 90,000 troops near Ukraine, after completing a series of large-scale drills, including with airborne troops. By early 2022, the number of Russian soldiers stationed on the border reportedly grew up to 190,000.

Ukraine and its EU allies were not alone in ringing alarm bells. As early as October 2021, US intelligence briefed the White House on a prepared Russian multi-axis attack on Ukraine in the upcoming winter. Subsequently, US representatives crossed the Atlantic to convince their European allies, Germany and France in the first place, of the immanence of a Russian invasion. But EU leaders, fearing ‘unnecessary provocations’ towards Moscow, were reluctant to launch Ukraine’s military training mission.

EUMAM UA. Status: Confirmed

It took eight months of full-scale invasion for the EU to complete its negotiations on the training of Ukrainian troops. In November 2022, the EU launched the EU Military Assistance Mission in Support of Ukraine (EUMAM UA). The reasons behind it were two-fold: first, the EU mission helped NATO distance itself from the Russo-Ukrainian War. This countered Russia’s ‘NATO expansion’ narrative, despite significant membership overlap in the two organisations. Second, the coordinated EU-level mission stopped member resources from being allocated to earlier established, non-EU programmes.

Notably, EUMAM UA is the first military training mission organised on EU territory. Run by the EU’s Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) HQ in Brussels, EUMAM UA has two coordination centres: Special Training Command (ST-C) in Germany’s Strausberg, coordinating training in Germany, and Combined Arms Training Command (CAT-C) in Poland’s Zagan, in charge of pan-European coordination. The two-year training mission, worth €107m out of the European Peace Facility, envisions training 40,000 Ukrainian soldiers by mid-November 2024. In addition to the two host countries, 24 EU member states, as well as Norway, the US, and the UK, have complemented EUMAM UA with training modules, military equipment for lethal and non-lethal purposes, and trainers.

EUMAM UA links Ukraine’s war-time combat skills needs with EU training capabilities. On the Ukrainian side, appropriately trained personnel is required to maximise the effectiveness of Western-made weapons systems. The availability of such personnel also ensures that equipment supplies are not minimised under the pretext of Ukraine lacking trained weapons operators. EUMAM UA weapons systems training includes courses on tactical use, repairs, and maintenance of weapons systems, already delivered to Ukraine, such as the Patriot air defence system, the PzH 2000 self-propelled howitzer, the Marder infantry fighting vehicle, IRIS-T missile systems, MARS II rocket launchers, and the Leopard 1 and Leopard 2 main battle tanks.

On the European side, the goal is to train Ukraine’s soldiers in line with the Western approach of ‘uniform combined arms training focusing on mission command from the brigade level down’. This means that Ukrainian military personnel should not only learn how to operate Western-provided military systems, individually and in units of varying sizes. They should also be able to combine army ‘capabilities in a simultaneous manner to prevail’. Ukrainian troops are being trained to execute such tasks as integrating different types of troops, weapons systems, and arms to achieve mutually complementary effects; synchronising, and not sequencing, phases of military operations; and delegating decision-making. Training courses designed to address these needs include combined arms combat in open terrain, night and urban warfare, offensive and breaching operations, UAV integration, de-mining operations, air defence, artillery, infantry combat, cyber, and medical support.

Challenges of EUMAM UA’s first year

A fully-fledged analysis of EUMAM UA is not yet possible, as the training mission is still ongoing. Still, an initial assessment of the mission – relying on feedback from trainers and trainees, field research, and analysis of battlefield developments – is useful to identify shortcomings and to make recommendations to improve the mission.

Lack of Time

Forming a cohesive military formation, both in personnel and equipment, can provide a decisive advantage in battles, even against a numerically superior opponent. But this requires time. In peacetime, creating a cohesive brigade of professional soldiers takes between one and two years. A UK infantryman has 28 weeks to complete one basic and one specialised training bout; an army officer would receive three years of training before stepping into a war zone. War-time reality does not operate on such a time scale. In the first EUMAM UA year, Ukraine could only send its soldiers away from the frontline for 4-6 weeks of training. Any longer absence from the frontline reduces Ukraine’s troop density, thereby increasing risk of tactical failures. But even such time-bound vocational training puts a strain on its battlefield stability. The ongoing counter-offensive is a case in point. To train its soldiers in the EU for this military operation, Ukraine had to keep its frontline brigades on minimal rotation over winter 2022 and spring 2023. One such trade-off was the Donbas city of Bakhmut, where soldiers faced a worse attrition ratio.

Moreover, Ukraine’s pool of professional soldiers is diminishing. In the course of Russia’s invasion, Ukraine increased its army from 300,000 to some 1mn people by mobilising reservists and civilians. These two groups of soldiers, aged between 19 and 71, comprise two-thirds of the Ukrainian trainees sent to EUMAM UA training. The high number of (relatively) inexperienced soldiers necessitates a stronger focus on basic training of individual skills to the detriment of collective training. It also increases personnel demands on the training side. To train one battalion of Ukrainian soldiers requires one battalion of German trainers. Language barriers create additional hurdles: the Bunderswehr uses 300 translators per day on average to train Ukrainians 12 hours a day, six days a week.

The EU objective of training a mix of civilians and Soviet-style educated soldiers into cohesive Western-equipped military brigades in just a few weeks is impossible. Ukraine is stuck in the dilemma. Extending the training time of Ukrainian troops is not feasible during the current counter-offensive, as it would reduce Ukraine’s troop density to dangerously low levels. Ukraine’s only possibility to extradite itself from this dilemma is to plan as far in the future as possible in an attempt to identify potential opportunities for efficiency. At the current time, there is no significant efficiency to be gained between now and the EUMAM UA‘s expiration in mid-November 2024.

Shifting Training Needs To Adjustment to War Realities

Ukraine’s 2023 counter-offensive has demonstrated Russia’s ability to successfully introduce battlefield adjustments. Some of these are context specific, such as the increased density of minefields from 120m to 500m. Others will have more impact on Russia’s doctrinal development, such as the dispersal of electronic warfare systems and relying on more precise targeting. Ukraine will have to counter these changed battlefield approaches for as long as it takes to secure the complete liberation of all of its territories.

The Russo-Ukrainian War’s dynamic tactical situation poses a challenge for EUMAM UA, because its training must reflect the changes on the battlefield. Current attempts to adapt EUMAM UA training seem limited in their success. Ukrainian soldiers, interviewed for this policy brief, repeatedly praised training courses teaching operation of Western-produced weapons systems or basic soldiering. However, tactical and strategic training proved to be out of context on the Ukrainian battlefield. For example, Western trainers suggested simply bypassing Russian minefields, not realising that these minefields can be dozens of kilometers wide. Additionally, current safety regulations in the EU and NATO, designed to prevent training accidents, prohibit the creation of effective crash courses. Ukrainian troops, limited to a maximum of six weeks of EU training, cannot learn basic and advanced skills at the same time. As a result, troops return to Ukraine not fully prepared to fight against artillery weapons and uncrewed aerial vehicles.

On the one hand, it is Ukraine’s military command making executive decisions on the type and duration of Western training courses. Hence, one way to alleviate this problem would be for the country’s armed forces to consider involving lower-level commanders with fresh battlefield experience in training design processes.

On the other hand, divergences between Western training and Ukraine’s frontline realities stem from changes in European armies’ profiling of their potential enemies. In the post-Cold War era, a likely military conflict profile has shifted from a classical armed invasion into guerrilla-type, low-to mid-intensity warfare against poorly equipped insurgent forces or terrorists. Such ‘out of area’ interventions, i.e., operations beyond the EU borders, gave European militaries equipment, information and air superiority advantages, as well as NATO and US back-ups. Fighting Russia’s army, even in its current state of disarray, means sustaining a full-scale conventional war at home against a near-peer enemy with a considerable manpower advantage. Throughout its war in Ukraine, Russian forces have relied heavily on overwhelming fire power of cannon and rocket artillery, greatly enhanced by the employment of uncrewed aerial vehicles and other high-tech surveillance assets. For European armies, this necessitates re-evaluation of doctrines, weaponry, tactics, and training, as the latter’s profile has also shifted to anti-insurgent fighting. This rendered the initial process of designing the training mission for Ukraine far more complex. France, for instance, even declined to host EUMAM UA on its territory, citing its fighting specialisation in the Sahel and the Middle East.

Inherited and Exported Defence Stocks Fragmentation

EUMAM UA trains Ukrainian soldiers on a few Western weapons systems, primarily those produced by German manufacturers. It makes EUMAM UA training more efficient and streamlined, but does not match the variety of weapons systems in use by Ukraine’s armed forces. Ukraine did request Germany’s ST-C training command to focus on raising the interoperability of its troops. But Germany’s efforts are limited to those troops that made it to EU-based training. This means that EUMAM UA-trained and equipped troops will be severely diluted with Ukrainian servicemen who were unable to practice Western-style fighting in the EU and/or do not know how to operate matching equipment. This creates two major questions for Ukraine’s battlefield replication of Western training. First, what is the optimal frontline combination of Western-trained and -equipped brigades with military units equipped with Soviet-era legacy weapons systems? Second, how to satisfy logistical needs of this ‘military zoo’, in the words of Ukraine’s former Defence Minister Reznikov?

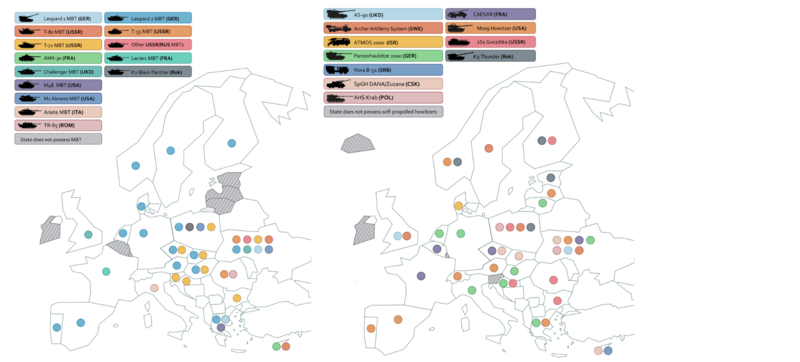

These two problems were largely exported to Ukraine from the EU. Despite decades-long efforts of NATO’s EU member states to improve the interoperability of their troops, this task remains on the Union’s defence to-do list. In 2016, the diversity of Europe’s major weapon systems, deployed in service of their ground, air, and naval forces, surpassed the US’ by a factor of six. In regards to European ground forces, the sheer diversity of main battle tanks, armoured infantry fighting vehicles, and howitzers surpasses that of the US by a factor of 13. With its military assistance to Ukraine, EU member states have also exported this fragmented array of equipment to Ukraine’s armed forces. Since February 2022, only EU countries donated Ukraine five different types of main battle tanks.

Types of main battle tanks (left) and self-propelled artillery (right) in use or ordered in the 27 EU states, the UK, EFTA states, and Ukraine

The second, logistical, problem is a consequence of weapons systems fragmentation. To proper organise their logistics, modern armies seek to maintain a ratio between combat units and support units, or the so-called tooth-to-tail ratio, of up to 1:10 or 1:15. In other words, an army requires 10-15 support personnel for every soldier fighting the enemy. Ukraine’s hot front line is running through five regions for over 1,200km. This distance is longer and has a more peculiar terrain than, say, a stretch between Berlin and Paris. Every frontline-based military unit requires a reliable supply of often incompatible ammunition, spare parts, and fuel. Some of these components, such as Soviet-era weapons systems, are no longer in production or produced in Russia and its partners. When it comes to maintenance, not all specialists are interchangeable among differently-equipped troops. Hence, a fragmented fleet of advanced weapon systems forces Ukraine to maintain a similarly fragmented pool of specialised fighting forces, exponentially increasing the army’s tooth-to-tail ratio. The need to maintain combat and support units, using an inherently incompatible range of weapons systems, further dilutes EUMAM UA training insights along the Ukrainian frontline.

How to Increase EUMAM UA‘s Impact

The first year of the EUMAM UA training mission will not change the outcome of Ukraine’s current counter-offensive. Still, its cumulative impact, as well as adjustments on both the trainers‘ and trainees‘ sides, will still count for its troops. To increase its long-term impact, the EU should commit to funding and running EUMAM UA not just until its current due date in November 2024, but well beyond that time frame. This should coincide with ramping up European production of ammunition and equipment for the related weapons systems.

Extending EUMAM UA

The EU should extend EUMAM UA by closing the 2025-2027 funding gap. Contrary to EU claims of supporting Ukraine ‘as long as it takes’, the Union keeps running into last-minute aid allocation hurdles. Hungary’s refusals to greenlight aid for Ukraine is a case in point. Repeated disruptions of timely funds allocation hamper Ukraine’s military planning ability and add fuel to claims of alleged Western aid fatigue.

Ukraine must better prepare for the upcoming stages of war by planning longer term with the planning horizon currently limited to just the EUMAM UA expiration in mid-November 2024. As the ongoing counter-offensive demonstrates, Ukraine needed at least five months to prepare this operation, largely to train its troops in the EU. By extending the EUMAM UA training mandate, the EU will lengthen Ukraine’s planning horizon and allow the country’s armed forces to send their troops away from the frontline for longer periods. The mandate extension will also facilitate creating more tailor-made training formats for various Ukrainian troops. For instance, Ukraine can lengthen the duration of training for specific military units, instead of setting the training length via a default version of a maximum of six weeks.

The EU should extend the current EUMAM UA mandate as soon as possible. The European External Action Service has already proposed this exact measure in a draft plan of multi-year security commitments to Ukraine. To implement this recommendation, the EU will need to top-up the European Peace Facility (EPF) budget, one of the key sources of the EUMAM UA funding. EU member states have been reportedly discussing a corresponding measure to establish a €20bn EPF fund to aid Ukraine for the next four years. As of now, the EU is unlikely to finalise the EPF top-up decision until after the European Council summit in December 2023 at least. Speeding up the EUMAM UA extension negotiations is also required for national governments, the other major EUMAM UA funder, to allocate money for the mission extension.

The training mission is likely to be initially extended until the end of the current long-term European budget Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), i.e., until the end of 2027, due to existing EU long-term budget constraints. This would be a good first step. Still, the EU should simultaneously articulate its readiness to fund EUMAM UA beyond the current MFF, if this necessity remains.

Standardising the content of EUMAM UA courses

Bringing Western training closer to Ukraine’s battlefield realities requires adjustments on the side of the EU and hosting countries. The solution to this problem is two-fold. The EU Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) should standardise the content of EUMAM UA courses across EU countries, while providing more freedom to select a set of courses tailored to the needs of a specific batch of trainees.

The EUMAM UA mandate extension should come in conjunction with adjustments to training playbooks. In general, EUMAM UA requires standardisation of the content of EUMAM UA courses, ideally complemented by post-training standardisation assessment. Currently, only national requirements for training exist, what risks reducing a cumulative training impact on Ukraine’s military unit cohesion. The EU Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) should designate a specialist to coordinate standardisation of EUMAM UA training, in close coordination with Germany’s Special Training Command and Poland’s Combined Arms Training Command, across all involved armies. This training standardisation should also ensure larger involvement of Ukrainian soldiers in training design. Ukraine possesses a unique first-hand experience in fighting conventional peer-to-peer war at home. Europe’s ability to integrate these skills into training routines means preparing fresh Ukrainian soldiers to match the on-the-ground conflict profile fought in Ukraine.

In parallel, European trainers should exercise more freedom in selecting courses tailored to the needs of a specific batch of trainees. In the first year of EUMAM UA, Ukraine’s military command made executive decisions on the type and duration of Western training courses. This should remain so, complemented by the involvement of Ukrainian lower-level servicemen in training design. However, EUMAM UA should proactively offer Ukraine courses that go beyond its explicit wishlist. The Special Training Command in Germany, for instance, is about to introduce such an adjustment: Ukraine will be given prearranged bundles of courses to choose from for the second year of EUMAM UA. The EU’s Military Staff and Poland’s Combined Arms Training Command should also adopt this approach. Or even take a step further: Ukrainian soldiers, for instance, could receive basic training on weapons systems which have not been yet approved for transferring to Ukraine. As EUMAM UA courses do not envision full-scale recreation of combat conditions, Ukrainian soldiers can already train on complex weapons systems, such as missile systems. This step might help reduce a time gap between obtaining approval for specific weapons systems and their battlefield use.

Merging EUMAM UA With Other EU Military Aid Measures

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU established two military aid mechanisms to assist Ukraine in addition to EUMAM UA: The Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP), which mobilises €500mn to ramp up the production of ground-to-ground and artillery ammunition and missiles, and The European Defence Industry Reinforcement through common Procurement Act (EDIRPA), a €300mn package aimed at incentivising EU-level cooperation in defence procurement. All three support mechanisms will expire in succession: EUMAM UA in mid-November 2024, ASAP in July 2025, and EDIRPA in December 2025. The result is that EU military aid for Ukraine is at risk of ‘defence shutdown’.

Running these three aid mechanisms separately risks misaligning which weapons systems are trained and which are procured for Ukraine. The EU should combine EUMAM UA with other two EU military aid measures under unified or single administrative supervision. The EU is already discussing a potential integration of some of its support measures. ASAP and EDIRPA are to evolve into a long-term European Defence Investment Programme (EDIP) aimed to incentivise joint defence development and procurement. The EU should add a training component to this package.

In the short-term, combining all three EU measures under unified administrative supervision will help bridge Ukraine’s training courses on Western equipment with weapons systems and ammunition procured for Ukraine’s armed forces. Initially, the EU could just set up communications channels between the departments overseeing these three aid mechanisms. In parallel, European countries should focus on consolidating a more limited range of weapons systems at greater scale to reduce their fragmentation along Ukraine’s frontline.

In the long-term, bringing three EU military aid mechanisms under unified or single administrative supervision will contribute to gradual alignment of EU training missions with EU joint procurement projects. If EU training missions are to remain the key approach to crisis prevention, crisis management, and post-crisis rehabilitation, this administrative merger of training and procurement mechanisms can further strengthen the EU position of an independent security actor.

Conclusion

The EU Training Mission in support of Ukraine (EUMAM UA) allows Ukrainian troops to maximise the utility of Western weapons systems and battlefield tactics in its fight against Russia’s invasion. One year into its life, its positive effects are marked, although the room for improvement to maximise its impact is considerable. Irrespective of the outcomes of Ukraine’s counter-offensive, EUMAM UA-provided competencies will remain relevant for the future liberation of Ukrainian territories. In turn, European armies will benefit by gaining insights from the only country with unique first-hand experience in fighting conventional peer-to-peer war on its own soil.

With the introduction of a domestic military training mission, the EU has made yet another step towards becoming an independent security actor. This widening of EU crisis response mechanisms is evidently in demand: Moldova, for instance, has expressed its wish to improve its defence and security, particularly by undergoing military training with Western partners. By further adjusting its training missions to serve the longer-term needs of its partners’ armed forces, the EU can be better prepared for future conflicts. Only this way can the EU remain a credible peace actor capable of teaching how to fight.

Photo: CC Multinational Special Training-Command (MN ST-C).