The challenges of enforcing sanctions against Russian oligarchs have brought the problem of financial secrecy to the fore. Governments in the EU lack the information necessary to identify, locate and freeze the assets of Vladimir Putin‘s entourage. What is missing is an EU-wide asset register that would not only shed light on the wealth of sanctioned individuals, but also help in Europe‘s fight against financial crime. This policy brief outlines the steps needed to build an interconnected EU asset register based on existing data collection requirements. Such a register could be practically implemented in the context of the ongoing overhaul of the EU anti-money laundering legislation.

In response to Russian president Vladimir Putin’s brutal war against Ukraine, the EU and its partners enacted sanctions against Putin’s entourage and other members of the Russian political and economic elite. The allies agreed to cut off these individuals from the financial system, freeze their assets and block their property from use. However, it is proving difficult to effectively crack down on the assets of Putin’s cronies, who often make use of sophisticated concealment practices that can hide not only the real owner of wealth, but also its location and sometimes even its very existence.

The leaders of the European Commission, France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States therefore committed to launch a transatlantic task force on the implementation of financial sanctions. As a practical proposal to end the wealth secrecy benefiting Russian tycoons, Italian Prime Minister Draghi proposed the creation of an international register of Russian citizens owning assets worth more than ten million euros. A global wealth register would indeed help identify, locate and freeze the assets of Russian elites and their family members – their yachts, safe deposit boxes, company shareholdings and real estate property.

However, Draghi’s proposal has two major drawbacks. First, to make a global register work, all major financial centres in the world would need to participate. Second, the problem of wealth secrecy is much larger than the handful of Russian individuals that Western countries have placed on their sanction lists. Financial opacity is the basis for financial crime more generally, which is estimated to amount to between 117 and 210 billion euros per year in Europe alone. The creation of a wealth register should therefore not be limited to Russian oligarchs.

Launching such a register at the European level would be a realistic undertaking. EU member states have already established national registers for some types of assets. This pre-work could form the basis for an EU asset register. Setting up such a European register would take time and therefore not immediately solve the problem of enforcing the sanctions following Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. But it would give EU governments an effective tool to better enforce sanctions in the future and vastly improve Europe's ability to fight money laundering and terrorism financing.

To pull illicit financial flows out of the dark, this paper proposes an interconnected EU asset register. The ongoing review of EU anti-money laundering legislation offers the chance to close the gaps in the existing national asset registers and link them to build a fully-fledged EU asset register overseen by a European anti-money laundering authority (AMLA), which the Commission has proposed to create.

1 Why we need an EU asset register

The recent Suisse Secrets revelations, the largest-ever leak from a major Swiss bank, have demonstrated once more how ‘offshore’ structures help drug lords, corrupt officials, fraudsters, and sanctioned individuals to hide dirty money or send it around the globe unnoticed. With the aim to remain in the dark, criminals set up complex networks of companies and trusts through which they control their real estate property, financial instruments or luxury goods. They name middlemen as directors of their companies or install nominees as official trust beneficiaries to further disguise their wealth ownership. Finally, they hold their riches outside of their country of residence and establish the intermediate undertakings in a third country.

Cross-border arrangements prove effective in concealing wealth because national police, tax inspectors, and law enforcement bodies only have access to the information they collect for themselves. There are possibilities for exchanging information among different authorities within one country and between authorities from different countries. However, decentralised data storage, incompatible data formats, and overly strict data protection rules hamper the smooth exchange of information. As a result, national authorities trying to freeze the wealth of sanctioned persons or investigate the criminals behind illicit financial flows struggle to track down assets and identify the real owners. Hence, according to Europol, only about 2% of suspicious assets are seized and only 1% are ultimately confiscated.

To put an end to financial opacity, national authorities would need to have access to a central register listing all different types of assets and their respective owners. Such a register would have to cover all EU member states in order to be able to trace ownership across national borders. National authorities would then be in a position to check whether any real estate on their territory belongs to a sanctioned individual, or identify the individual benefiting from the money in a safe deposit box held by a foreign company suspected of drug trafficking. Importantly, an EU asset register would not create new privacy concerns: it would merely pool existing information collected at national level and make it centrally available to competent authorities in all member states, which are already subject to EU data protection rules.

Status quo of available information on asset ownership

In the EU, there is no central register of who owns which asset. At the national level, however, the fifth EU Anti-money Laundering Directive (AMLD5) forces each member state to create ‘transparency registers’ for companies and trusts established on their territory. These transparency registers show the beneficial owner, i.e. the person(s) who ultimately owns or controls a company or a trust. It is not the member states who collect the information, but companies and trusts who must provide information on their beneficial owners to the registers. The transparency registers not only help to identify the real owners of a company or a trust, but they also allow for the tracing of the final beneficiary of a bank account or any other asset held by a company or a trust. Member states are free to build one register for both companies and trusts, or to set up two separate registers, one for companies and one for trusts. The European Commission has recently set up the dedicated Beneficial Ownership Registers Interconnection System (BORIS) to interconnect the national transparency registers. The interconnection allows authorities in one member state to search assets or beneficial owners recorded in the register of another member state through a joint interface.

In addition to the transparency registers for companies and trusts, each member state is obliged to create a national bank account register detailing which person owns which bank account. Banks and other financial institutions must provide this information to their domestic register. If the bank account holder is a company or a trust registered in the EU, the relevant national authority can turn to the transparency registers to identify the person behind the company or trust that ultimately controls the bank account. The 27 national bank account registers have not yet been interconnected, but the European Commission has proposed a bank account register (BAR) single-access point to link them in the future.

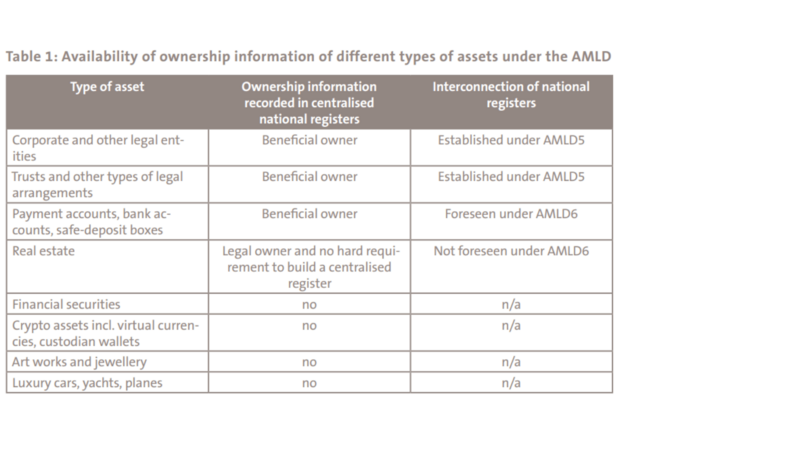

Furthermore, member states are asked to ensure that their national competent authorities have access to information on the legal owners – not the beneficial owners – of real estate within their territory. There is no obligation to build national centralised real estate registers where they do not exist. Any means “which allows the identification in a timely manner” is permitted, so it is sufficient for competent authorities to be able to manually retrieve land register entries. As central real estate registers do not exist in all member states, the future legislation proposed by the European Commission (AMLD6) does not foresee an interlinkage of the information collected at the national level. Table 1 gives an overview of the ownership information collected for different types of assets under the current and future AMLD.

Source: Own Research

Significant gaps in financial transparency

All this means that there are significant gaps in the transparency of who owns which assets in the EU. First, several member states have not set up national transparency registers yet, although the EU obligation to establish registers for companies and trusts has been in place since January and March 2020, respectively.

Second, the transparency registers for companies and trusts do not include all companies and trusts active in the EU. In the company register, member states must record only companies incorporated within their territory. As a result, the beneficial owners of a non-EU company holding for example a bank account within the EU cannot be traced. In the trust register, member states must also record trusts from outside the EU, but only if they have bought real estate in the EU or started a new business relationship with an EU client after March 2020, when member states were required to launch their trust registers. Consequently, non-EU trusts that acquired real estate in the EU or established a business relationship before March 2020 are missing from the national trust registers.

Third, the national transparency registers do not display beneficial owners for all companies and trusts included in the registers. The reasons for this are twofold. First, the current legislation limits beneficial ownership to persons controlling more than 25% of the shares or voting rights. Thus, a company with four shareholders or a trust with four trustees which each hold a quarter of the voting rights has no beneficial owner, as no single person has a share exceeding 25%. Second, member states often neglect their obligation to keep the information recorded in the transparency registers up to date and do not regularly check whether the information provided by companies and trusts is accurate and complete. As a result, many entries in national transparency registers are lacking information on beneficial owners.

Fourth, for real estate, member states are not obliged to build national centralised registers and the information made available to competent authorities includes only the legal owners and not the beneficial owners. The requirements for real estate property fall short of the EU standard established for bank accounts, where member states must put in place centralised automated mechanisms that directly provide information on the beneficial owner. Given the importance of real estate for money laundering, the possibility for beneficial owners of real estate to hide behind legal owners and the lack of directly available information constitute a tremendous shortcoming.

Fifth, for several types of assets, the national registers are not interconnected across borders. Through the BORIS interface, national authorities can access data recorded in the transparency registers of any EU member state and thus look up the beneficial owners of companies and trusts. However, the national bank account registers are not interconnected, and the European Commission has only suggested concrete measures to do so in its proposal for the AMLD6. Linking the national real estate registers is not foreseen at all by the Commission since member states do not all have centralised registers in place. Voluntary projects to make real estate ownership information available across the EU have not delivered the much hoped-for results. Consequently, authorities in one member state cannot directly access the information stored in the bank account and real estate registers of another member state, but must send requests for information and wait for a reply. This situation unduly complicates law enforcement investigations and asset seizures.

Sixth, national registers do not cover all relevant assets. Although financial assets are a key component of households’ overall wealth, national registers include only bank accounts, and not securities nor crypto assets. National registers are also missing for artwork, jewellery, luxury cars, yachts and planes. The latter must be registered according to national law, but member states are not required to collect beneficial ownership information.

2 How to establish an EU asset register

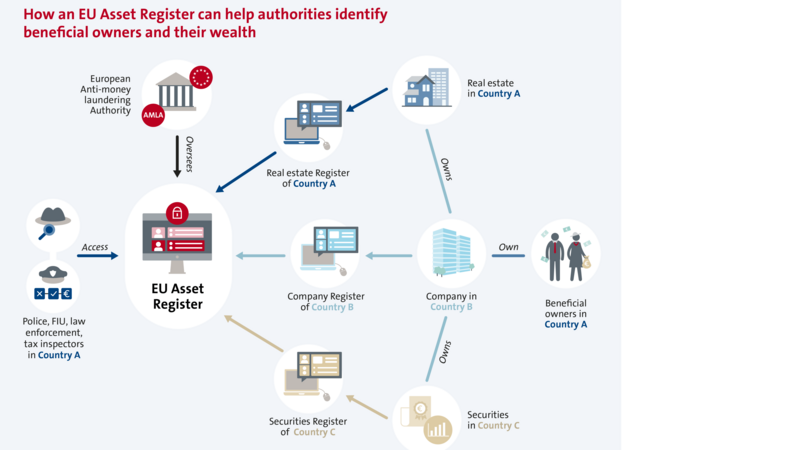

On July 20, 2021, the European Commission presented the latest package of amendments to the EU’s anti-money laundering legislation. The European Parliament and the Council are currently discussing the Commission’s proposals. The ongoing review provides the unique chance to now adopt the changes necessary to establish a comprehensive EU asset register. Importantly, the necessary steps do not require setting up an entirely new register at the European level, but only a doable extension of existing data collection requirements at the level of EU member states. An EU asset register can be built relatively easy by plugging the gaps in member states’ national asset registers and then linking them together. Figure 1 shows how this would allow competent authorities such as police, financial intelligence units (FIU), law enforcement and tax inspectors throughout the EU to quickly find the beneficial owner behind a specific asset, or the assets that a specific person owns.

Source: Own illustration.

Creating an effective EU asset register requires four steps that should be taken in parallel:

- Every asset recorded in the national register should be assigned to a beneficial owner.

- There should be national registers for all relevant assets located in the EU.

- The national asset registers for the different types of assets should be linked to each other so that ownership information is accessible by responsible authorities across the EU.

- The new European anti-money laundering authority (AMLA) should oversee the EU asset register to ensure the quality and protection of the data collected by member states.

2.1 Provide complete beneficial ownership information

Knowing the beneficial owner of an asset is the prerequisite for a meaningful asset register. However, the current threshold of more than 25% for the identification of beneficial owners makes it too easy for criminals to escape sanctions, taxation and criminal prosecution. The EU should therefore follow best practice and lower the threshold for the identification of beneficial owners to 10%. Furthermore, member states should record in their real estate registers not only the legal owners but also the beneficial owners. Providing beneficial ownership information should become the standard for any asset recorded in a register. Last but not least, member states should be obliged to ensure that every registered asset is assigned to a beneficial owner. Member states should be required to provide the financial, human and technical resources necessary to regularly check the registers, investigate missing information on beneficial owners and sanction entities that do not comply with their reporting obligations.

2.2 Cover all relevant assets

A comprehensive asset register should be an inventory of all assets known to be misused for financial crime purposes. Instead of registering all assets held in the EU, it is sufficient to cover the ones that are most relevant from a money laundering perspective. This includes financial assets and expensive goods purchased to introduce illegal profits into the financial system, then companies, trusts and investment vehicles used to disguise the source of wealth, and finally the real estate, luxury assets and business ventures where dirty money eventually ends up.

Recording all relevant information in the EU requires two things. First, the transparency registers for companies and trusts should also cover foreign entities with EU-relevance. Non-EU companies should be included in the national company register of every EU member state where they are active. Member states’ national trust registers should include non-EU trusts where they hold real estate or do business. The inclusion of foreign entities would reflect recent recommendations by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog.

Second, member states should be required to establish national registers for all relevant assets that are not yet registered. Regarding financial assets, member states should create additional registers for securities and crypto assets. Furthermore, they should register expensive artwork and jewellery as well as luxury cars, yachts and planes where their prices exceed certain thresholds.

2.3 Link national asset registers

The beneficial ownership information recorded in national asset registers will only support police and law enforcement across the EU if the information collected in one member state can be easily accessed by the responsible authorities in all member states. The technical conditions for the interconnection of the national transparency registers for companies and trusts exist and the European Commission has also proposed to interlink member states’ bank account registers. Going forward, interconnection of national registers should become mandatory for all types of assets recorded in national registers, including real estate. If filled with machine-readable data, interconnected registers would allow for cross-checks, analysis, and the application of big data techniques to identify patterns. Linking all national registers would create a database where competent authorities can search the assets owned by a specific person and vice versa. This would enable asset identification, location, freezing and confiscation where warranted.

2.4 Ensure oversight at the EU level

Since EU member states collect the beneficial ownership data for assets located on their territory, they should remain the owners of the data. However, a comprehensive EU asset register connecting national asset registers from 27 member states requires some form of management at the EU level. The European Commission provides the technical details and conditions for linking the existing registers on companies, trusts and bank accounts. On top of this, there should be an EU body ensuring the quality and protection of the data gathered at the national level. A natural candidate for European oversight of the EU asset register would be the new European anti-money laundering authority (AMLA) proposed by the European Commission. The AMLA is meant to improve cooperation among member states’ financial intelligence units and to coordinate national anti-money laundering authorities. As the centrepiece of an integrated system of national supervisory authorities, the AMLA should also ensure that information member states share through the interconnection of registers is accurate, regularly updated and safe from unauthorised access.

3 Conclusion

Financial secrecy is the breeding ground for financial crime and currently prevents authorities from freezing the assets of sanctioned Russian individuals. Italian Prime Minister Draghi is therefore right to call for a register of assets that would reveal who owns what, but he is wrong to limit it to Russian oligarchs. Authorities should be able to identify, locate and seize the wealth of kleptocrats regardless of their nationality. By making ownership information available to all relevant authorities, an EU asset register would substantially dismantle financial secrecy and thus reduce the blind spots that enable financial crime in the first place. Last but not least, EU governments should ensure that public authorities have the financial and human resources necessary to make use of the financial transparency measures proposed in this paper. If complemented with an increase in police and law enforcement resources at the national and EU level, an EU asset register has the potential to drain the swamp of financial crime in Europe.