Following the activation of the Temporary Protection Directive, Lucas Rasche argues in this Policy Brief that member states must urgently transition from crisis-response to developing a longer-term strategy for implementing temporary protection. This requires member states to shift from a reactive to a forward-looking policy. The Brief outlines four areas that will require particular attention in the months ahead: the disproportionate allocation of refugees across EU countries (i), the long-term financial costs of hosting refugees (ii), devising a tailored integration strategy (iii) and preparing for beneficiaries of temporary protection to transit into a durable protection status (iv). The Policy Brief then concludes by discussing the potential spill-over of activating the Temporary Protection Directive to the wider EU asylum policy.

Introduction

Four months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent displacement of more than seven million refugees, it is now time for the EU and its member states to transition from a humanitarian response to a longer-term strategy. The EU’s initial response to the arrival of 5.1m Ukrainian refugees was characterised by an unusual mix of openness and pragmatism. Activating the Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) - for the first time since its adoption in 2001 - has in particular proven to be politically apt. That decision has helped ensure immediate and comprehensive access to protection without putting too much of a strain on national asylum systems. Even more so, it shows that the EU and its member states do have the capacity to take in and accommodate large numbers of refugees – if the political will exists.

The Temporary Protection Directive has often been dubbed the “sleeping beauty” of EU asylum policy. Yet, the EU’s sudden love for the TPD must not blind it to the fact that the true value of activating it will be determined by outcomes. Hence, EU heads of governments should not rest on their laurels. Instead, they should acknowledge that activating the TPD is just the opening shot in a longer-term challenge to receive and integrate Ukrainian refugees – not another crisis response completed. Member states should now focus on addressing the challenges that have emerged from the decision to activate the Directive. They will further have to devise a forward-looking policy for making real the rights and entitlements that come with temporary protection status. This will require the EU’s migration and asylum policy to shift from reactive to proactive.

Four aspects will need particular attention by member states in the months ahead. These concern the envisioned balance of efforts in hosting Ukrainian refugees (i), the long-term financial costs (ii), devising a tailored integration strategy for Ukrainian refugees (iii) whilst preparing for beneficiaries of temporary protection to transit towards a durable protection status (iv). Recent progress in negotiations on the Commission’s new Pact on Asylum and Migration mean member states should also reflect on lessons to be learned from granting temporary protection for the wider EU asylum and migration policy.

This Policy Brief first discusses why the EU’s response towards Ukrainian refugees needs to shift from crisis response to longer-term strategy. It then analyses four areas of policy-making that will require attention by member states and the Commission when implementing temporary protection. Finally, the Brief discusses the potential impact of activating the Temporary Protection Directive on negotiations to reform the Common European Asylum System (CEAS).

1. Shifting from crisis mitigation to a forward-looking policy

Member states’ decision to activate the Temporary Protection Directive on 4 March 2022 had two main objectives. First, it sought to prevent national asylum systems from being overburdened. Contrary to the regular asylum system, the TPD does not require an individual asylum assessment before issuing protection status. Hence, it alleviates member state authorities of the onerous task of individually processing the asylum applications of more than 5m Ukrainian refugees. Second, the Directive grants those fleeing the war in Ukraine immediate protection. While it often takes months before an asylum decision is issued, beneficiaries of temporary protection can directly make use of rights associated with their status, including access to the labour market, education, healthcare and the right to family reunification.

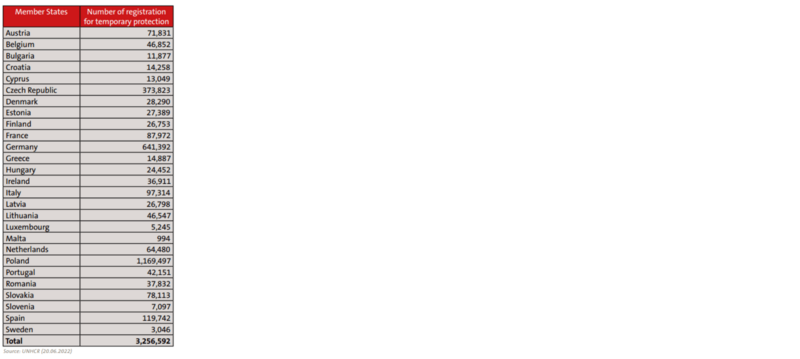

The EU’s swift and pragmatic response has so far proven to work. Of the estimated 5.1m Ukrainian refugees who arrived in Europe in recent months, 3.2m have so far registered for temporary protection in one of the EU member states (see table 1). The fact that some 1.9m people are still to claim protection shows that there remain immediate challenges that require attention. Yet, member states should equally start to address the longerterm challenges that arise from activating the Directive. The 2.5m Ukrainians who have returned home according to UNHCR should thereby not delude EU leaders into thinking that the bulk of their work is already accomplished. For one thing, these returnees are most likely to travel back and forth, visiting family members and friends, rather than permanently returning to their war-torn home. And more importantly, because effective implementation of temporary protection requires adding a longer-term strategy for taking in and integrating Ukrainian refugees.

Such long-term planning has been absent from much of the EU’s asylum and migration policy in recent years. Instead, the EU has been operating in constant crisis mode. Ever since the arrival of more than one million refugees in 2015, onward movement across EU countries has become synonymous with a perceived loss of control, while the objective of reducing the number of irregular arrivals continues to shape negotiations about reforming the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). Trying to prevent a repeat of 2015 has thus led EU asylum and migration policy to be characterised by short-term thinking, ad hoc measures and the gradual externalisation of asylum responsibilities to third countries.

Yet, the absence of a crisis narrative in the EU’s initial response to those fleeing the war in Ukraine has now broadened the spectrum of political options. It has also bought member states time to mitigate the absence of a blueprint for implementing the Temporary Protection Directive. EU member states must now use their swift response to devise a strategy that takes into account experiences made in recent weeks, whilst equally accounting for the uncertainty deriving from the unclear trajectory of the war in Ukraine. The lack of experience in implementing temporary protection thereby requires EU countries to anticipate challenges rather than managing them as and when they arise. The following section explores four areas of policy making that demand particular attention.

2. Implementing temporary protection: four issues that require attention

2.1. The (im)balance of efforts to host Ukrainian refugees

So far, the uneven distribution of Ukrainian refugees across EU countries has been of little concern to member states. However, the disproportionate pressure put on the reception and integration capacity of a handful of EU countries may become a crucial challenge for implementing temporary protection in the months ahead. Poland (1,169,497), Germany (641,392) and the Czech Republic (373,823) have so far registered the most refugees for temporary protection (see table 1). Even though the data suggests that other member states neighbouring Ukraine, such as Hungary (24,452), Romania (37,832) or Slovakia (78,113) received fewer Ukrainian refugees, slower registration processes are likely to misrepresent the burden on these countries. Given the presence of a Ukrainian diaspora within these countries, as well as the scope for relatively easy back-and-forth travel due to their geographic proximity with Ukraine, it would be unrealistic to assume that Ukrainians will eventually disperse evenly across EU member states.

However, pressure on reception and integration capacities in many of these countries is likely to increase as refugees are unable to return home on a permanent basis. The deliberate dismantling of national asylum systems in Poland or Hungary further makes it harder to provide adequate reception and integration in countries of first refuge. The absence of state facilities to take in those fleeing the war thereby risks permanently outsourcing responsibility to civil society actors, who may feel overburdened, exploited or simply left to fend for themselves. More importantly, it could prevent Ukrainian refugees from making full use of their rights under the Temporary Protection Directive.

It therefore remains important that EU member states work towards establishing a better “balance of efforts” as envisioned in the Temporary Protection Directive. Instead of a formal relocation scheme, member states confirmed the right to free movement for Ukrainian refugees across EU countries and agreed not to apply Article 11 of the TPD, hence pledging not to return a person if they had already registered for protection in another EU country. Moreover, transport hubs were established to inform refugees of their rights and possibilities for (free) onward travel, while a dedicated Solidarity Platform is sought to centralise work to organise bilateral transfers and match reception capacities in individual EU countries.

These measures form the basis on which member states must build when transitioning from crisis response to longer-term strategy. Two objectives should guide this strategy. First, the EU should increase its support for civil society organisations that have helped with hosting Ukrainian refugees. Research shows that public sentiment towards refugees can easily change over time as people start to care less about the reasons for displacement, but instead worry about the domestic economic costs of hosting refugees. Reports about “refugee fatigue” highlight the need to go beyond financial compensation for civil society organisations and invest in state capacity to provide adequate housing, schooling, language training and employment opportunities for refugees.

Second, member states must increase their efforts to better facilitate the onward travel of Ukrainian refugees. This is certainly the case for the transfer of Ukrainian refugees from Moldova. While member states like Germany (2,500), France (2,500) and Austria (2,000) all pledged to provide reception capacities, the small number of flights that took off from Moldova indicates that few refugees have benefitted from these offers. Lengthy registration and screening procedures, bureaucratic processes as well as poor communication to refugees have so far hampered an efficient implementation of such transfers. Disinformation about reception conditions may also (negatively) impact peoples’ decision whether to agree to a transfer. In the absence of efficient and easily accessible transfers, refugees are likely to organise their own onward travel, which may increase the risk of trafficking – especially for women and children. The EU should hence work towards streamlining registration and matching procedures involving IOM, UNHCR, local authorities and the relevant member states, while also taking refugees’ aspirations to stay or to move on into account.

These efforts should be complemented with measures that guarantee the free movement of Ukrainian refugees between EU member states in the months ahead. This would include ensuring that a person does not lose their status as a beneficiary of temporary protection when re-entering the EU from Ukraine after a residence permit has been issued in one of the member states. It also requires the Commission to ensure member states keep their borders open to Ukrainian refugees. In 2015, the perception of migration as a potential security threat eventually led six Schengen countries (Germany, France, Austria, Denmark, Norway and Sweden) to introduce – and uphold – internal border controls. A recent judgment by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) considered these as contrary to EU law. The clear limits on the possibility of reintroducing and extending border controls set out in the judgement should serve as benchmarks for the Commission to approach any attempts by member states to curtail the right to free movement under the TPD.

2.2. Financing the long-term costs to integrate refugees

The Commission was quick to set up a financial support scheme for member states particularly affected by the arrival of Ukrainian refugees. In total, some 17 billion Euros were mobilised, mainly by re-organising previously unused EU cohesion policy funds through the CARE and CARE+ initiatives and by permitting member states to make use of the 2022 REACT-EU tranche to finance support measures for Ukrainian refugees. So far, the Commission has paid nearly 3.5 billion Euros in advance to member states as part of REACTEU. Among those EU countries particularly affected by the arrival of Ukrainian refugees, Poland received the largest amount of additional pre-financing (560m), with Romania (450m), Hungary (299m), Czech Republic (283m), Bulgaria (148m) receiving slightly less.

These funds were predominantly used to cover the costs arising from member states’ immediate humanitarian support to Ukrainian refugees. When transitioning from crisis response to implementing temporary protection, the Commission will therefore need to prepare for longer-term support for member states’ efforts to host Ukrainian refugees, as these will likely remain disproportionally dispersed across EU countries (see 2.1) and require comprehensive integration support (see 2.3 below). A challenge in this regard is to determine the precise costs of receiving and integrating Ukrainian refugees. Some estimates predict up to 43 billion euros in the first year alone. However, these calculations are largely based on experiences with the reception, accommodation and integration of people who went through a regular asylum procedure. Both the scale of current arrivals, as well as the different operational and legal framework of the TPD, hence make such numbers only partially useful.

Another challenge is the fact that the current resources available to member states under the EU budget do not constitute fresh monies. This includes the potential use of AMIF funding for the 2021-2027 period, which is limited to 9.9 billion euros in total, with 60% already being pre-allocated to member states. Moreover, AMIF funding is technically foreseen only in support of short-term integration, while longer-term integration is supposed to rely on EU social and regional funds. Similar difficulties arise with regard to options discussed by Rubio, which include tapping into the 2021-2027 cohesion funds or re-allocating RRF funding to the objective of Ukrainian refugees’ longer-term integration. Hence, member states and the Commission will have to discuss whether they are willing once more to reallocate considerable amounts from other parts of the EU budget, or whether they are able to mobilise fresh financial resources for the longer-term integration of Ukrainian refugees.

Regardless of the funding instrument, the Commission faces a particular challenge in ensuring money is in fact dispersed in the way initially intended. Under the ESF+, for example, no money is ringfenced for the specific objective of socio-economic integration of migrants and refugees. Without amending the funding rules of the ESF+, the Commission retains limited control when it comes to ensuring that member states unwilling to prioritise integration of Ukrainian refugees do use these funds correctly. To that end, the Commission should also ensure that funds are more easily available to local community and civil society actors, who often find it hard to deal with the administrative process of applying for EU (co-)funding.

2.3. A tailored integration strategy

Another crucial test for the EU’s longer-term strategy towards Ukrainian refugees regards integration. Unlike people undergoing a regular asylum procedure, Article 12 of the Temporary Protection Directive grants its beneficiaries direct access to the labour market after registration. Theoretically, this should allow for a smoother integration process as gainful employment is considered crucial for status and self-reliance, as well as access to social networks. In practice, however, member states must start devising integration strategies that account for these refugees’ specific characteristics.

So far there is no comprehensive overview of the exact demographic composition of refugee flows from Ukraine or of refugees’ educational level and professional qualifications. According to the UNHCR, 90% of those fleeing the war are women and children. The OECD estimates that more than 80% are of working age. Generally, Ukrainians have high educational levels, with 83% of the population having completed tertiary education. Whereas the overall employment rate of Ukrainian women (44%) before the war in Ukraine is slightly lower than that of men (57%), most women are employed in the service sector (75%) while another 14% work in industrial jobs. High educational levels, professional experience and cultural proximity of Ukrainians may well aid their labour market integration.

When drafting integration policies, a major challenge for member states will be to ensure these skills can be applied to the domestic labour market. Most migrants and refugees face difficulties in matching their experience and skills to the conditions of their host country’s labour market. Refugees in particular run the risk of working beneath their qualifications. The Commission addressed this issue by proposing a Recommendation to organise how professional qualifications should be recognised in the case of beneficiaries of temporary protection and called on member states to “reduce the formalities for recognition of professional qualifications to a minimum”. Still, member states should complement a simplified recognition of formal qualifications with measures to assess and validate informal but transferable skills. Such competence checks were developed in several member states following the 2015 refugee arrival and can serve as helpful starting points to better facilitate the labour market integration of Ukrainian refugees. Based on the assessment of refugees’ existing skills and needs, member states should then provide tailored support through vocational education and training (VET) programmes, language courses and social support from day one.

Another issue member states must take on board is the need for comprehensive childcare offers. As many displaced persons have caring responsibilities, adequate day care for minors is an essential prerequisite for them to make use of language courses or vocational and educational training. This is particularly relevant for refugee women, who face distinct challenges arising from the general gender pay gap as well as from an employment gap when compared to their local peers. Further, member states should step up mental health services provision to address many refugees’ need for psychological counselling in order to deal with potential anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Lastly, a particular challenge arising from the situation of Ukrainian refugees regards the war’s uncertain trajectory. Member states will therefore need to devise an integration strategy which deals with the possibility of refugees’ indefinite stay whilst equally preparing them for a potential return. Such “dual intent” integration should aim at keeping refugees’ skills alive not just to help them integrate into the host society, but also to prepare them for a potential reintegration back home. Ensuring refugees’ skills are put to use is crucial for successful economic integration. This in turn can help facilitate refugees’ ability to join in the future rebuilding of Ukraine, either through sending remittances or by contributing their skill-set upon return.

2.4. From temporary protection to durable solution

By activating the Temporary Protection Directive, member states agreed to initially grant those coming under its scope immediate protection for one year until March 4, 2023. Should the reasons for displacement persist, that status is automatically extended up to twice for a period of six months each. After March 4, 2024, the Council can then extend temporary protection for a further year. By 4 March 2025, the current temporary protection regime thus expires. While three years may seem like a long time, member states are well advised to start planning how beneficiaries of temporary protection can transition into a more durable protection status.

In principle, giving the duration of temporary protection an expiry date was a good decision. Experience from applying temporary protection in Turkey shows that indefinitely prolonging temporary protection can in due course hamper beneficiaries’ socio-economic integration. The Turkish government’s initial expectation that Syrian refugees would swiftly be able to return home has led to inadequate long-term planning, leaving beneficiaries of temporary protection with neither the perspective of permanent residence nor safe return.

While the EU’s current temporary protection scheme should remain time limited, drafting a long-term perspective requires that the Commission and member states accept the possibility that many Ukrainian refugees will need protection beyond 2025. The grim perspective of a war of attrition in eastern Ukraine renders a safe return to this part of the country impossible in the near future. Whereas other parts of Ukraine could become relatively stable, the sheer scale of the destruction caused by heavy artillery shelling might nevertheless make a return for many Ukrainians a remote possibility. In fact, most forced displacements tend to become protracted – meaning those affected remain in a precarious situation for at least five years. On average, displacement for refugees can even last 20 years and more than ten years for those internally displaced.

When preparing for the long-term stay of Ukrainian refugees, member states will need to clarify whether these are to remain based on a protection status, or whether they should acquire regular residence status. Most temporary protection beneficiaries are likely to qualify for international protection, either through refugee status or subsidiary protection. Preparing to grant Ukrainians a long-term status that accounts for their protection needs would therefore be the ideal scenario. Yet, this would require member states to continue issuing protection through a group-based status definition rather than via individual asylum assessments. Otherwise, national asylum authorities would likely be overwhelmed by the task to transfer people from temporary protection to a refugee status on a case-by-case basis.

Another option to establish a longer-term perspective for Ukrainians regards the possibility of a so-called “lane change” into regular residence status. Currently, long-term residence status is granted to persons who have legally and continuously resided in a member state for five years. However, the Long-term Residence Directive excludes beneficiaries of temporary protection from its scope. In order to make a ”lane change” possible for Ukrainians, the Commission would thus have to revise its recently proposed amendment to the Long-term Residence Directive by waiving the exemption for those benefitting from temporary protection.

3. Learning the lessons of temporary protection: What impact on the CEAS?

Beyond devising a strategy for implementation of the Temporary Protection Directive, there is a need for member states and the Commission to reflect upon how experiences made from granting temporary protection can be transferred to the EU’s wider asylum policy. Benefits from swift access to protection and integration services are one thing to consider in this regard. Providing refugees with the agency to decide on their country of residence, as opposed to the rigid but often dysfunctional Dublin rules, is another. Moreover, the role played by civil society in creating the capacity and political leadership to take in refugees is something member states should build on when devising future asylum and integration policies. The way in which EU member states responded to the arrival of 5.1m Ukrainian refugees showed that mobilising the capacity and financial means to cope with a mass inflow of refugees is less an issue of resources, but political choice. In particular, the absence of a “crisis narrative” has broadened the spectrum of policy options and helped frame the welcoming of those fleeing the war in Ukraine as a measure of solidarity rather than an unwanted repeat of 2015.

However, activating the Temporary Protection Directive has also exposed the inherent double standards of EU asylum policy, as well as highlighting member states’ different treatment of asylum seekers dependent on the geopolitical context of their arrival. This is most evident in Poland, where the country’s border with Ukraine remains open, while asylum seekers crossing from Belarus are denied the possibility of lodging an asylum claim – often by use of force. Negotiations on the (recently agreed) solidarity mechanism also underline that member states’ apparent unity, on show in activating the Temporary Protection Directive, is unlikely to last. Rather than having all member states commit to receive asylum seekers, the mechanism merely foresees voluntary relocations by a coalition of willing member states. EU countries can even issue preferences as to the nationality and vulnerability of migrants who are then relocated, hence manifesting the highly variegated treatment of different groups of protection seekers. Resurfaced discussions about externalising asylum responsibilities to third countries by replicating the United Kingdom’s deal with Rwanda further illustrate that deterrence remains a major objective of EU asylum policy.

Activating the Temporary Protection Directive was a historic decision. In the months ahead, member states must decide whether this decision will remain a singular event, or whether the benefits of temporary protection can create spill-over effects to other areas of EU asylum and migration policy. If anything, member states should resist the temptation to use their welcome for Ukrainian refugees as an excuse for increased deterrence against other groups of asylum seekers.

Conclusion

So far, the EU and its member states have successfully coped with the largest refugee movement since the Second World War. The pace and volume of arrivals in the first few weeks following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine naturally prompted a series of ad hoc measures. Now that the first phase of responses is well underway, the EU must shift from crisis response to developing a forward-looking policy for integrating Ukrainian refugees. The lack of experience with implementing temporary protection thereby poses a number of challenges for EU member states. The disproportionate allocation of Ukrainian refugees across EU countries (i), the longterm financial costs of hosting refugees (ii), devising a “dual intent” integration strategy for Ukrainian refugees (iii) and preparing for beneficiaries of temporary protection to transit into a durable protection status (iv) will require member states’ particular attention in the months ahead. Activating the Temporary Protection Directive for the first time since its adoption in 2001 has been a bold decision. Yet, it will be member states’ ability to turn that immediate achievement into an effective, long-term strategy that is now the acid test.