Labour shortages are a common challenge for EU member states. Shortages in sectors vital to the green and digital transition risk attaining common objectives of the EU’s industrial strategy. But as much as the need to attract skilled workers is a shared concern, the EU lacks a common labour migration policy that lives up to the challenge. In this Policy Brief, Lucas Rasche argues that the EU’s current labour migration acquis is highly fragmented, underused, and largely detached from other policy areas. Hence the EU needs to structurally re-think its approach to labour migration for it to truly compete in the global race for talent.

1. Introduction

Presenting its New Pact on Asylum and Migration in 2020, the European Commission justified the need for reforming labour migration policy by declaring that “the EU is currently losing the global race for talent”. Doubling down on this assessment, Commission President von der Leyen called for 2023 to be the European Year of Skills. Besides investment in training, upskilling, and better job-matching for the domestic workforce, a crucial aim is to “attract skills and talent from third countries”.

The Commission’s initiative comes at a time when the EU’s labour migration policy evidently requires a re-think. With ageing societies and a decline in the working age population, European labour markets are under severe pressure as employers in all member states struggle to fill vacancies. Labour shortages in key sectors of the EU economy jeopardise common policy objectives. This is most evident with regard to the twin green and digital transition which is hampered by structural labour shortages in the IT and construction sectors. However, the EU’s current legal migration acquis fails to rise to the challenge. It is overly fragmented and complex. Existing Directives remain largely ignored by member states. And the legislative framework operates without clear objectives and largely detached from other EU policy areas.

The more recent recast of individual Directives may help improve their respective functioning. But such incremental changes remain insufficient to address the structural shortcomings of the EU’s labour migration acquis. What is more, proposals for a Talent Pool and Talent Partnerships put forward in the Migration Pact have thus far not gained much traction. For one, because member states have historically been wary to cede competences on labour migration to the European level. And second, because political and financial resources have in recent years almost exclusively been channelled towards reducing irregular arrivals to the EU. As a result, there is the impression that asylum policies are a common European concern, whereas labour migration remains solely a national issue. However, this is misleading. With labour shortages manifesting themselves as a common European challenge, they also require a common response. To that end, a broader reform agenda is needed that ensures economic competitiveness and allows the EU to truly compete in the global race for talent.

2. Labour shortages as a common European challenge

Labour shortages across all member states pose a considerable and growing challenge to the EU economy. Demographic pressures along with a strong – though uneven – economic recovery post-pandemic have increased the pressure on labour markets. Estimates from Eurostat suggest that this pressure will increase drastically in the years ahead: the share of Europe’s working age population is expected to decline from 64% of the total EU population in 2022 to around 54% in 2100. Harnessing the full potential of the domestic labour force, for example by increasing women’s employment as well as by up- and re-skilling are necessary, yet insufficient measures. The EU must then attract migrant workers from third countries. In Germany alone, the country’s employment agency estimates that an additional 400,000 migrant workers are needed each year to mitigate labour market shortages.

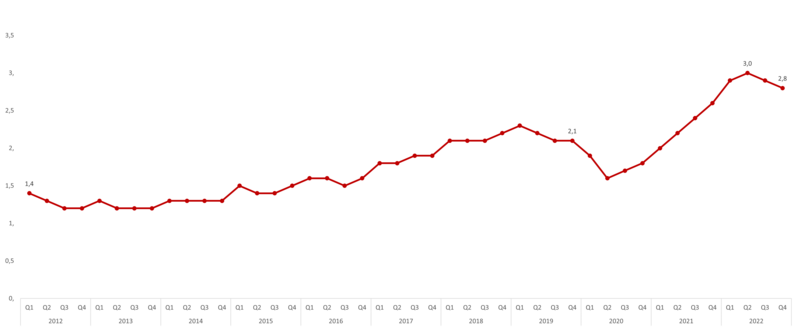

Labour shortages are already jeopardising member states’ economic competitiveness. Indeed, data from Eurostat shows that the EU’s average job vacancy rate has increased significantly, doubling from 1.4% in 2012 to 2.8% at the end of 2022 (see Chart 1). The rate depicts the number of job vacancies expressed as a percentage of total occupied posts and the number of job vacancies. While the rate took a brief dip in 2020 as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, it rose sharply as the EU’s economy started to recover from the pandemic. It went on to reach a historic high of 3% in the first quarter of 2022. Even a slight decrease in the second half of 2022, following the war in Ukraine, has barely reversed the trend. In the fourth quarter of 2022 (2.8%), the vacancy rate still remained 0.7% higher than pre-pandemic (2.1%).

Chart 1. Job vacancy rate in EU27 (2012 – 2022)

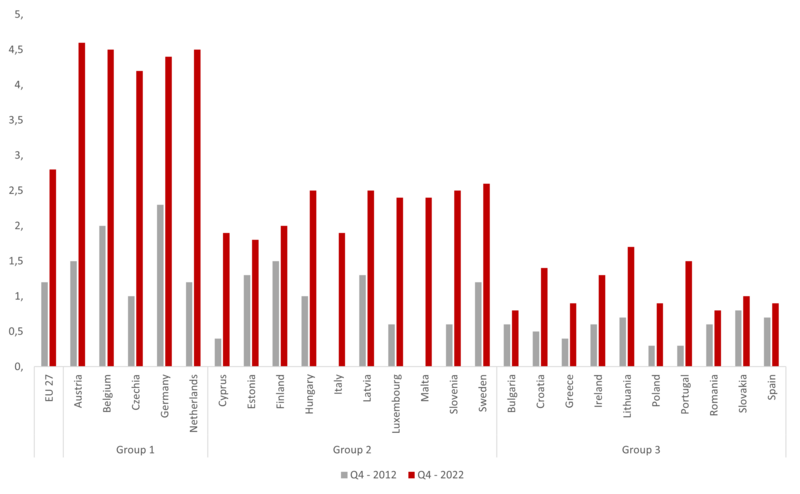

Labour shortages are thus very much a common European challenge. This is illustrated by the fact that the upward trajectory of the average EU job vacancy rate does not just reflect the position in a handful of countries Indeed, comparing the rate in individual EU member states for 2012 and 2022 shows that difficulties to fill vacant positions have gradually worsened in all EU countries (see Chart 2).

Some EU countries are harder hit by labour shortages than others. Broadly speaking, three groups of member states can be identified. First, there is a group most severely affected. These countries have witnessed a steep increase in their job vacancy rate over the past decade. At end of 2022, the unmet demand for labour was most pronounced in Austria, with a vacancy rate of 4.6% compared to merely 1.5% in 2012. In both Belgium and the Netherlands, the rate was 4.5% in 2022 – up from 2% and 1.2% respectively. Similarly high numbers were recorded in Germany (4.4% in 2022 versus 2% in 2012) and the Czech Republic (4.2% in 2022 v 1% in 2012).

A second group (Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, Slovenia and Sweden) is experiencing a vacancy rate similar to the EU average of 2.8%. Although none of these countries has a rate more than 1% below the EU average in 2022, they are all confronted greater difficulties in filling vacant positions when compared to 2012. The third group consists of member states whose job vacancy rate remains below the EU average, hence not exceeding 1.8% (Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain). Nevertheless, the job vacancy rate has increased considerably in some of these countries. For example, it has more than doubled in Poland (from 0.3% to 0.9%) and Lithuania (from 0.7% to 1.7%). It even increased fivefold in Portugal, from 0.3% in 2012 to 1.5% in 2022.

Chart 2: Job vacancy rate per member state (Q4 2012 & Q4 2022)

A similar pattern is evident in a 2022 study by the European Labour Authority (ELA) which finds that countries in the EU’s north-west have particular difficulties meeting demand for labour. EU countries submitting the highest number of shortage occupations were Italy (205), the Netherlands (166), Belgium (164), Slovenia (107), Denmark (106), Estonia (97), France (77) and Finland (60). As research from Eurofound shows, recruitment difficulties had been a major obstacle to production in the industry, services and construction sectors. Again, this phenomenon was particularly recognisable in north-west as well as central and eastern European countries whilst the economic output of firms in southern European countries appeared less affected.

2.1 The case for a common EU response

A closer look at the types of occupations with shortages identified by member states shows that such shortages risk the attainment of common EU objectives. Based on research from the European Labour Authority (ELA), these can be ascribed to four main sectors. Most shortage occupations were registered in the construction sector. Of the 29 countries (EU27 plus Switzerland and Norway) analysed by the ELA, 19 registered bricklayers and related tasks as shortage occupations. Some 18 countries lacked carpenters, welders and plumbers. Shortages are also prevalent in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) professions. This is particularly the case for software developers and engineers, one characterised by many EU+ countries as “severe shortages”. Both the services and healthcare sectors have also come under the cosh from labour shortages, most obviously during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Shortages in the construction and IT sectors are particularly problematic for common objectives as they risk undermining EU industrial strategy and its ambition to steer member states through the twin green and digital transitions. Between 2014 and 2022, the job vacancy rate in the IT sector rose in all European countries, with the exception of Croatia, Greece and Ireland. Over this period, the unmet demand for labour increased particularly in Belgium (+5.1%), the Netherlands (+4.6%) and Austria (+4.0%). Although overall employment in the IT sector has risen over recent years, the European Commission estimates that member states will lack 20 million experts in areas like cybersecurity and data analysis by 2030.

Labour shortages may also negatively impact upon implementation of the EU’s climate policy and the green transition. The Commission’s Fit for 55 Package, for example, is expected to result in a “structural shift in employment away from carbon-intensive sectors and to increase the demand for jobs in sectors contributing to the greening of the economy”. One of the sectors relevant to the EU’s green transition is construction. Estimates by vocational training agency Cedefop predict the sector will require 3-4m more workers to meet the targets set by the green transition. The Commission expects that its envisioned “Renovation Wave Strategy” alone could require an additional 160,000 new jobs in the EU construction sector.

Left unaddressed, current structural labour shortages in both the construction and the IT sectors can hence have a detrimental impact on the Union’s green and digital transition. There is thus a case for EU industrial strategy to be complemented with a labour migration component. So far, member states are responding to the shortages challenge largely by adjusting their national schemes. The German government, for example, has put forward a series of legislative initiatives that are supposed to facilitate labour migration from third countries and make the country more attractive to foreign workers. Spain also adapted its immigration policy to ease the labour market integration of foreign workers and make the processes of issuing work permits more flexible. Similarly, the French government presented a new bill that would allow for the naturalisation of undocumented migrants working in sectors characterised by labour shortages. Both Slovakia and Romania recently lifted restrictions on migrants from third countries with a view to simplifying their labour market integration. And even Hungary, otherwise known for its hard-line resistance to immigration, has opened up to labour migrants who help ease pressure on the country’s service sector.

However, relying solely on national solutions comes at the risk of further fragmentation and economic divergence. Some member states are in a better position to attract migrant workers from third countries than others. This may be the result of language and cultural ties stemming from colonial history. Another crucial factor is the size of national labour markets, which puts smaller EU countries at a natural disadvantage in attracting foreign talent. Larger labour markets offer more employment opportunities thus giving migrants the chance to better match their qualifications with vacancies and thereby avoid work in underqualified occupations. Considering the three groups of EU member states mentioned above, the job vacancy rate is particularly high in economically strong countries (Germany, Netherlands, Austria). Given the size and attractiveness of their labour markets as well as their acute needs to fill vacancies, these countries may well out-compete others in bidding for qualified workers. A coordinated European labour migration policy should thus aim at offsetting internal competition to ensure that all member states are capable of attracting the migrant workers necessary to manage the green and digital transition. Harnessing the potential of a single EU labour market, instead of operating as 27 separate labour markets, would also put the EU in a better position to compete for migrant workers internationally with the United States, Canada or Australia.

Whereas national labour markets differ in structure, three common threads can be identified that shape EU demand for labour. First, labour shortages are a shared European challenge as we've seen. The scale of unfilled vacancies may vary, but all EU countries have witnessed an increase in vacancy rates over the past ten years. Second, current shortage occupations can be categorised into four main sectors (construction, STEM, healthcare and services). But a closer look at the type of shortage occupations indicates that EU member states don't just need high-skilled workers. In the construction and services sectors the EU must find ways to facilitate the entry of lower- and medium-skilled migrant workers. Third, shortages in construction and IT related professions risk jeopardising common European policy objectives, most notably those of the twin green and digital transition. Relying on national solutions won't address the challenge, as intra-EU competition is likely to result in divergences between member states’ ability to fulfil EU industrial strategy objectives.

3. The EU’s labour migration policy: Hardly a common response

The EU’s mandate to legislate on legal migration is based on Article 79 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU) which states that the Union “shall develop a common immigration policy aimed at ensuring, at all stages, the efficient management of migration flows”. To that end, the EU may define “the rights of third country nationals residing legally in a member state, including the conditions governing freedom of movement and of residence in other member states”. However, Article 79 TFEU also sets very clear limits on EU competences in the field of labour migration. EU legislation “shall not affect the right of Member States to determine volumes of admission of third-country nationals”. While the wording of the EU mandate as regards labour migration policy is hence framed rather vaguely, full harmonisation is clearly not the objective. Without that, the Commission therefore opted to pursue a sectoral approach towards harmonising third country nationals’ admission and residence status.

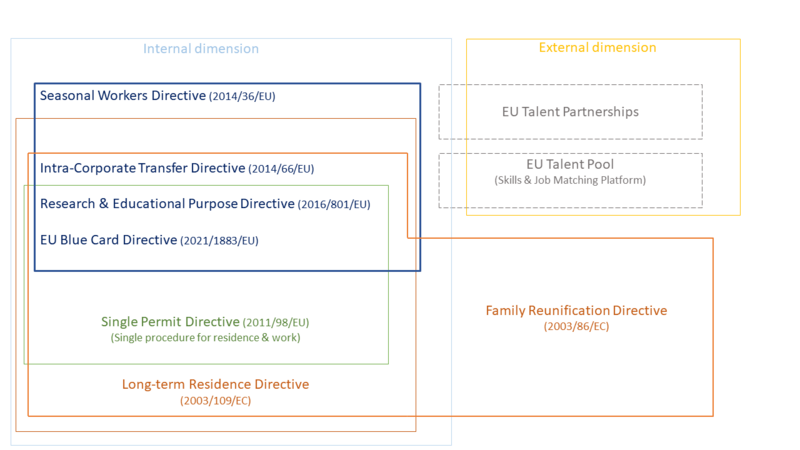

The result is a highly fragmented and overly complex framework that consists of a patchwork of several EU Directives and co-existing national legislation. Different categories of migrant workers are regulated by different Directives, each covering different aspects and stages of the migration process. To date there are seven pieces of EU legislation that regulate labour migration of third country nationals. These include four Directives governing the admission and associated rights of different categories of migrant workers: The EU Blue Card Directive for highly skilled migrants, the Seasonal Workers Directive, the Intra-Corporate Transfer Directive, and a Directive on the conditions of entry and residence for students and researchers from third countries (see Chart 3).

In addition, the Single Permit Directive aims at streamlining the residence and work permit procedures of applicants, as well as the rights associated with their eventual status. However, it only applies to the EU Blue Card and Research and Educational Purposes Directives – not to the intra-corporate Directive or seasonal workers Directive. The latter is also excluded from the scope of the Long-term Residence Directive, which regulates the necessary conditions and rights for obtaining that status. Yet another Directive further sets out common rules on the right to family reunification of third country nationals who lawfully reside in the EU. It applies to Blue Card holders, as well as to intra-corporate transferees and researchers.

Chart 3: EU framework on labour migration

These Directives are complemented by various national schemes that often operate in parallel to EU legislation. They explicitly grant member states the possibility to establish their own more favourable rules, which de facto means EU legislation merely sets minimum standards. Several “may” clauses within existing EU Directives further allow for much leeway in implementation. This adds to the internal incoherence of the EU’s legal framework on labour migration and creates “an overly complex landscape of rules, statuses and procedures”. In a 2019 Fitness Check, the Commission hence concluded that the sectoral approach was a key reason for the overall fragmentation of its legal migration acquis. The document also found that “more efficient interaction and synergies” with the EU’s overall growth and external policies are required.

3.1. EU legislation: Underused & not catering to needs.

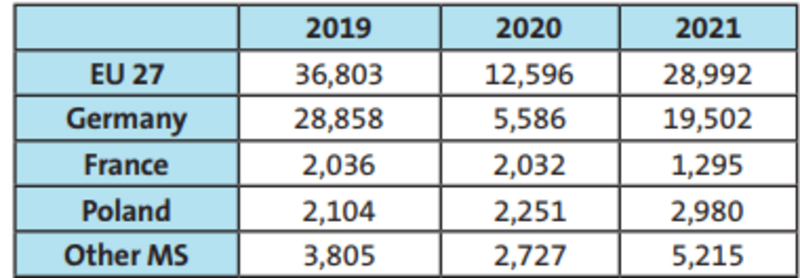

Given its complexity and fragmentation, there are few indications that – in its current shape – the EU’s legislative framework can add much value to mitigating labour shortages in the Union. Two examples illustrate why. First, relevant Directives are underused and do not sufficiently fulfil their purpose. The EU Blue Card is a case in point, as it has proven to be largely irrelevant to most member states. Out of 1.3 million permits issued for employment purposes in the EU in 2021, some 29,000 were Blue Cards, with the vast majority issued by Germany (19,502). That same year, German authorities issued almost twice as many Blue Cards as all other EU countries combined. In fact, only three member states (Germany, France and Poland) have issued considerable numbers of Blue Cards between 2019 and 2021, (see Table 2). A high threshold for eligibility, more favourable national schemes for high-skilled migrants, and failure to promote the Blue Card’s benefits have contributed to the directive's lack of attractiveness.

Table 1: Number of EU Blue Cards issued per year

Another example is the Single Permit, which is supposed to simplify the procedure for third country nationals to work and reside in the EU. In 2021 some 2.9 million single permits were issued across all 27 EU member states. Similar to the Blue Card, the modest number of single permits issued is partially because only a few member states have made any use of the Directive. 69.7% of single permits in the EU in 2021 were issued by France (1.1 million), Italy (443,000), Spain (325,000) and Portugal (208,000). The small number of single permits granted by other EU countries is emblematic of governments giving priority to national schemes and dodging away from EU migration legislation. Moreover, 65.9 % of single permits were issued to extend a current residence permit (62.6% for a renewal and 3.3% for change of status). Contrary to its initial purpose, the Single Permit has therefore done little to facilitate the entry of third country workers and failed to attract migrants to work in the EU.

Member states' hesitance to make use of EU legislation is certainly a result of the fact that EU rules allow for more favourable provisions to be made in national law. Hence the EU’s legislative acquis on labour migration reinforces rather than challenges or complements national preferences. Previous plans by the Commission to harmonise rules on the admission and residence status of migrant workers, as well as the initiative for an EU “immigration code” that would consolidate and extend existing legislation, have not materialised. The main reason for their collapse has been resistance from member states, which view labour mobility – and decisions over who enters and resides – as the preserve of national sovereignty.

Second, the existing legislative framework on labour migration is ill-equipped to cater to the needs of the green and digital transition. Current shortage occupations – in particular difficulties in filling vacancies in the IT and construction sectors – risk undermining objectives of the EU’s industrial strategy. IT-related occupations are more likely to be granted the EU Blue Card. For example, the average annual income for an IT specialist in Germany is 55,000 Euro, which would match the annual income of at least 43,992 Euros necessary for an applicant to qualify for a Blue Card in Germany. Yet, its meagre use historically casts doubt on whether the Blue Card can really provide much added value. Moreover, the EU’s current legislative framework provides no real opportunity for lower- and medium skilled migrants to enter the EU labour market even though they are urgently needed to fill vacancies in the construction and services sectors. Current EU legislation on labour migration appears to operate largely detached from wider policy objectives and lacks clearly defined objectives.

3.2. Reforms do not address structural shortcomings

In its Communication accompanying the New Pact on Asylum and Migration (2020), the Commission highlighted “the potential of migrant workers to contribute to the green and digital transitions by providing the European labour market with the skills it needs”. Despite this nod to the relevance of labour migration, the Pact does little to change the structural shortcomings in the EU’s legal migration acquis. Although some of the reforms and initiatives that ensued have the right intention, their overall ambition remains modest at best. That is certainly the case as regards proposals for establishing a so-called EU Talent Pool and Talent Partnerships with third countries. The initial idea for the Talent Pool was to match candidates in third countries more efficiently to job vacancies in the EU. Yet, lack of clarity on how to vet candidates, as well as uncertainty about the added value of any such Talent Pool and how it relates to the legal migration acquis have impeded implementation of the proposal. So far, only a pilot has been launched for refugees fleeing the war in Ukraine. The "Talent Partnerships" have so far none of the two evolved past the pilot project stage. Both initiatives are designed to bridge the divide between the internal and external dimensions of EU migration policy by tapping into the workforce of third countries and matching them to EU employment needs (see chart 3). Yet, recent discussions at the European Council have skewed their objectives away from serving as instruments to equip the EU with qualified labour migration. Rather than aligning Talent Pool and Talent Partnerships with, for example, the EU’s industrial strategy, they are increasingly thought of as leverage to pursue returns and deterrence policies which shows the EU has not yet heard the signs of the times.

Instead, such Partnerships are conceived as leverage to increase the number of returns and push through migration management objectives vis a vis third countries. These initiatives are misaligned with the objectives of EU labour migration policy.

Recently concluded revisions of the EU Blue Card Directive, as well as ongoing reforms of the Long-term Residence Permit and the Single Permit Directives, may help to improve their functioning. Lower and more flexible eligibility thresholds for the Blue Card, for example, can widen its scope, while the European Parliament’s proposal for a revised Long-term Residence Permit would make it easier for migrants to apply. The proposed recast of the Single Permit Directive aimed at simplifying and clarifying its scope may make it more effective – albeit without addressing entry conditions for lower- and medium-skilled migrants. Moreover, the Commission’s latest initiative on establishing a dedicated Labour Migration Platform may help coordinate member state policies.

4. Conclusion

Labour shortages are a common European challenge. Despite difference between national labour markets, all EU member states have experienced an increase in the job vacancy rate over the past decade. What is more, labour shortages in key sectors jeopardise common EU policy objectives. This is most evident with regard to the EU’s industrial policy where shortages in the IT and construction sectors hamper the twin green and digital transition. Left unaddressed, these shortages risk resulting in economic divergences between member states and undermining the EU’s economic competitiveness.

A common challenge hence requires a common response. However, the EU’s existing legislative framework on labour migration falls short of meeting the challenge for three reasons. First, the EU’s sectoral approach to harmonisation has rendered the current acquis fragmented and overly complex. Second, allowing member states to devise more favourable national rules and the sensibilities over national sovereignty as regards immigration policy has left EU legislation widely underused. Third, the existing framework on labour migration remains largely detached from objectives in other policy areas. This can be seen in the lack of Directives addressing the need for lower- and medium skilled migrant workers and the use of Talent Partnerships to push through migration management goals.

Recent reform proposals under the Migration Pact may improve the functioning of individual files. Yet, such incremental adjustments fail to address the structural shortcomings in EU policy. Moving forward, the EU must fundamentally rethink its policymaking in the area of legal migration. To that end, it must reconsider how best to harness the potential of a common labour market. A short-term option could include extending the current sectoral approach with legislation that specifically targets sectors relevant to industrial policy, most notably with regard to the green and digital transition. Yet, longer-term thinking is ineluctable. The EU must pursue and implement a common labour migration policy that avoids internal competition, clearly defines common objectives and aligns instruments to their end thereby putting the EU in a better position to compete in the “global race for talent”.