On 6 October 2022, the inaugural meeting of the new ‘European Political Community’ (EPC) took place in Prague. Moving from a vague idea, suggested in May by French President Macron, into a real-time meeting with more than 40 European leaders in just a matter of months was a success exceeding early expectations for the EPC. But this very success means that the EPC has been inaugurated before it acquired a clear purpose, agenda or framework. This policy brief traces the evolution of the EPC and illustrates possible models for its future shape to ensure that the EPC will be able to achieve more than just bringing together leaders for yet another photo-op.

On 6 October 2022, the inaugural meeting of the new ‘European Political Community’ (EPC) took place in Prague. Bringing together the heads of state or government of 44 European countries and the Presidents of the European Council and European Commission, its self-proclaimed goals are to

- “foster political dialogue and cooperation to address issues of common interest, and

- strengthen the security, stability and prosperity of the European continent”.

The programme was confined to one day, on the eve of the informal European Council summit on 7 October; it included bilateral meetings, plenary sessions and roundtable discussions on peace and security, as well as on energy, climate and the economic situation. No written conclusions emerged from its deliberations but rather, with stylised symbolism, a joint picture of the continent's leaders.

The EPC has moved from a vague idea, suggested in May by French President Macron, into a real-time meeting in just a matter of months. Bringing together more than 40 European leaders, including then British Prime Minister Liz Truss, an initial skeptic, so swiftly exceeded early expectations for the EPC. But this very success means that the EPC has been inaugurated before it acquired a clear purpose, agenda or framework.

Ensuring that the EPC will continue in being more than a mere symbolic photo-op, this gap needs to be filled in the coming months. This policy brief will explain the evolution of the EPC and illustrate possible models for its future shape.

From family of values to strategic forum

The EPC is the brainchild of French President Macron in direct response to the Russian war in Ukraine. He introduced the idea on 9 May 2022 in his speech celebrating the end of the Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFoE), one of his other brainwaves. Calling it “a historic obligation for Europe”, Macron proposed a new European platform, which would “allow democratic European nations that subscribe to our shared core values to find a new space for political and security cooperation, cooperation in the energy sector, in transport, investments, infrastructures, the free movement of persons and in particular of our youth.”

This idea was not entirely new. Late French President François Mitterrand made a similar proposal in 1989 but it failed to gain traction. In April 2022, Enrico Letta then raised it again, with Macron seizing upon it. After Macron’s speech, it quickly gathered supported by European Council President Charles Michel (albeit under the name ‘European geopolitical community’) in a speech on 18 May 2022, by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in his Prague speech on 29 August 2022 and by Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen in her State of the Union speech on 14 September 2022.

The initial idea

The idea itself underwent a big shift between May and October. The initial conception of the EPC was of an EU-centric organization. Based around the notion of ‘shared values’ and against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, the EPC was to be a way to give EU candidate countries improved perspectives of cooperation more rapidly than could be offered under the accession process, thereby anchoring them closer to the Union. This also explains the reasons behind the need for the new forum in the first place: its objectives were anchored in the wish to create a community with the European Union at its core, a goal that strengthening of the Council of Europe (CoE) framework, for example, would have failed to achieve.

This initial idea of creating the EPC as a concentric circle around the EU also reflected the traditional French preference for pushing ahead with EU integration in smaller inner circles. Creating an outer circle via the EPC would, from a French perspective, follow the same logic: it would offer both non-EU countries wishing to cooperate more with the EU and (ex-)member states seeking, au contraire, less cooperation a venue meeting their own objectives.

A shift in conception

This conception, however, then shifted with the European Council meeting on 23 and 24 June 2022, one preceded that same morning by an EU-Western Balkan Leaders’ summit. The idea moved towards a model less focused on enlargement (or its alternatives) and more geared towards strategic cooperation. The EU candidate countries in particular preferred the EPC to be a forum in which all participating countries could discuss common energy and security issues on the continent on an equal footing. The concept of a strategic cooperation forum was quickly embraced. French Secretary of State for European affairs, Laurence Boone, wrote on 24 August that the EPC was to be centred on cooperation on foreign policy and security plus interconnections in trade, research and education. This focus on cooperation made it also easier for Germany to support the proposition. Boone’s views were duly echoed by German Chancellor Scholz just five days later.

Inviting countries like Turkey or Azerbaijan to join the EPC’s inaugural meeting must similarly be seen against this background. Extending an invitation to (semi-)authoritarian countries was – rightly – met with critical questions as to its compatibility with the previous idea of an initiative based on common values such as democracy. A security-oriented format, however, could more comfortably allow for the strategic decision to include Azerbaijan and Turkey, the latter already a NATO partner.

Crucially, the security focus removes any sense of rivalry with the Council of Europe, making it more comfortable for the two fora to co-exist. Even though their memberships are almost identical (only Andorra, San Marino and Monaco are part of CoE but not EPC), there is little overlap in their fields of action as has also been pointed out by the President of the CoE Parliamentary Assembly, Tiny Knox. The Council of Europe, which also includes the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), remains the sole pan-European community dedicated to defending human rights, democracy and the rule of law on the continent.

The first meeting

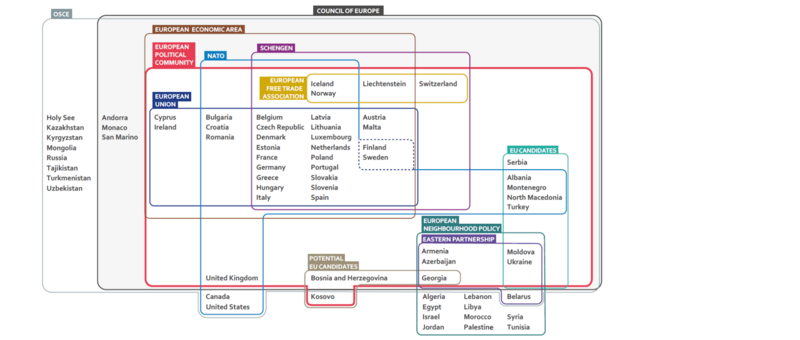

The final participation list in the EPC’s inaugural meeting included the leaders of the 27 EU member states, the four countries of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), the six Western Balkan countries, five Eastern partnership countries (excluding Belarus) and Turkey as well as the Presidents of the European Council and of the European Commission. The graph below shows the composition of the European Political Community and how it relates to the membership clusters of other fora for political cooperation in Europe.

The fact that the first meeting of the EPC took place not even five months after the idea was first floated is largely down to France and the Czech EU Council presidency; as host Prague had a decisive say in how the inaugural event was organized. The meeting on 6 October was finally organized around two roundtable discussions on 1) peace and security, and 2) energy, climate and the economic situation. Each roundtable was jointly facilitated by an EU member state and a non-EU country, following the model of the EU-African Union summit. Perhaps more important, however, is that the meeting’s agenda left space and opportunity for talks outside the plenary sessions. Most notably, a quadrilateral meeting between the President of Azerbaijan and the Prime Minister of Armenia together with the French President and President of the European Council took place, in which the two combatant countries reportedly made progress towards a peace deal.

The EPC will, at least for the next two years, meet twice a year. The next meeting will be hosted by Moldova in spring 2023, followed by Spain and the United Kingdom, thus alternating between an EU member state and a non-EU country. There is hence a framework for biannual meetings. But beyond that, there is no clear idea – and even some opposing visions - of what it is designed to achieve and how. This lack of clarity threatens disappointment instead of unity. In the following, different models for the role that the EPC could play for Europe in the future will be illustrated.

The way forward?

Deciding the EPC's final format depends on which primary goal the EPC is to achieve. The EPC was largely seen as a reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the need for a more geopolitical positioning of the EU on the European continent and beyond. At the same time, its creation reflects the failure of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), the problems associated with the EU accession process, the freezing of Turkey’s accession negotiations, and the uneasy relationship of the EU with the UK post-Brexit. These different issues cannot, however, command the same approach. Instead, different models will set different priorities as their main objective.

A facilitator and anchor for enlargement

The trigger for the EPC was Ukraine’s application to become an EU member, submitted shortly after the Russian invasion in February 2022. Ukraine's application (28 February 2022) was quickly followed by those from Moldova and Georgia (both on 3 March 2022). Ukraine and Moldova received candidate status at the 23/24 June European Council.

The path for aspiring EU member states to join the Union is notoriously long and painful, paved with a long list of reforms as pre-condition for membership. It takes an average of nine years to go from application to accession. This excludes current candidate countries, some of which have been in the EU’s waiting room for decades: Turkey, for example, has been a candidate country since 1999. In addition, by opening the membership door to Ukraine and Moldova, the question of what to do about the six Western Balkan countries resurfaced, where the problems of the accession process had become painstakingly clear. Staggered by a lack of commitment to the region on the Union’s side and a lack of progress on reforms on the EU's part, the decades-long accession processes in the region have essentially grounded to a halt. Disillusionment among the candidate countries led, on the one hand, to a shift in policy away from exclusive focus on EU membership. On the other hand, the EU has equally lost bargaining power and attractiveness in the negotiations with aspiring members.

Against this changed geopolitical backdrop, it was clear that a new approach was needed to anchor the EU’s nearer neighbours in greater proximity. One very common suggestion in the debate has therefore been that the European Political Community could serve as an additional anchor of stability and facilitator for enlargement. Here it would become a forum to assist candidate countries in their path towards membership, without differentiating among them and without giving each a sense that they will be able to accede faster than the others. One idea mooted is that EPC membership could automatically constitute the first step towards EU membership, unless a country decides otherwise. Within the EPC itself, the accession process could then be built up more gradually and based on equality and mutual trust rather than the bottom-down, take-it-or-leave-it approach currently defining the process.

This model does not seem very likely. The EPC’s proposed objectives have, as we have seen, shifted away from this concept. But even the EU candidate countries, the supposed beneficiaries of such a model, are not keen on it. And indeed, there is a risk that it could undermine the principle of equal footing: Even with the best of intentions, it cannot be ruled out that, in an EU-centric model, different tiers of members would emerge as already in several EU differentiated integration formats. On the one hand, non-EU countries would find it hard to push back against the will of the EU-27 bloc. On the other hand, countries wanting to join the EU would be under much more pressure to implement reforms or follow decisions taken by the EU-majority within the EPC than countries that have no desire to join. In such a format, the UK, Norway or Turkey could arguably object to suggested common projects much more easily than Ukraine or Moldova, thereby undermining the very idea of a joint community based on an equal footing among partners.

A bridge to the UK

The question of the future EU-UK relationship post-Brexit remains unsolved. To date, no regular European forum exists for the EU and the UK to exchange views, risking an even greater alienation between the two sides over time. Discussions between them remain dominated by the difficult trade-related negotiations. More political aspects of the relationship, such as security and defence, have in turn been marginalised.

The EPC could change this. It could serve as a bridge between the two by providing a platform for discussions on issues of common concern. While ex-premier Liz Truss was skeptical at first about joining the EPC, not only did she show up but the UK will also be the host of the fourth EPC summit after offering to stage the second. This was interpreted by many as a possible turning point in EU-UK relations. The less strictly formal nature of the EPC arguably also made it easier for the European Commission to accept the UK's inclusion even though the Northern Ireland Protocol impasse had not yet been settled.

If this model is to work, however, the EPC can neither become too EU-centric nor can it have a high degree of institutionalization. This has been made abundantly clear by the UK government, which has also suggested a name change into “European Political Forum” so as to avoid any resemblance to the EU’s forerunner, the European Community. Critically, the mere objective of bringing the UK back to the European table would be too narrow: It can and should be one goal of the EPC going forward, but only one of several.

An OSCE without Russia

The move away from a purely values-based forum for political cooperation to a security-focused one brings the EPC closer to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). The OSCE began life in the early 1970s and served as a multilateral forum for dialogue during the Cold War. It is based on a non-binding constitutive charter, which allows for flexible cooperation between all partners without opening up disputes over implementation. As a rule, the OSCE meets once a year at ministerial level. The heads of state or government of the participating countries meet on a less regular basis: since its inception in 1973, there have been just seven summits at the leaders’ level, the last one in 2010, at which the OSCE’s priorities are set. These summits only happen if convened by one of the leaders.

There are overlaps between the issues dealt with by the OSCE and by the EPC, which raises the question of whether it could be a model for the latter but without Russia and with a reduced range of topics, as the OSCE’s scope of activity also includes human rights and election observations for example. This would mean that the EPC would, at some point in the future, also include field missions in the participating states for e.g. data collection, capacity building or crisis management purposes. This model does not seem likely. Starting out as a forum for political dialogue, the OSCE is now more geared towards missions on the ground as opposed to high-level meetings for discussions on broader political topics. It also embraces a secretariat and its own parliamentary. All of these points can be ruled out as options for the EPC, for now at least.

A European Security Council without the US

The need to improve the EU’s capacity to act as a geopolitical player in security and foreign policy is not a new one. In this regard, France and Germany advocated for the creation of a “European Security Council” (ESC) already in 2018. While the idea never took concrete shape, one thought was to create a body consisting of rotating EU member states, which would act in close coordination with the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the European members in the UN Security Council (UNSC).

The EPC could serve as a way to implement Macron’s initial ideas of an ESC but with a wider regional focus, all the while excluding the United States. The absence of the US (unlike with NATO) is important in that it signals the intent for the EPC to be a way for Europe to acknowledge its own responsibilities. In fact, the EPC is considered by some to be a successor to the ESC idea, in particular when it comes to the goal of bringing the UK to the table. The aim behind the ESC was to facilitate faster common responses by participating states in security policy where there is broad political alignment. This means that in order for the ESC model to work for the EPC, sufficient agreement between all 44 EPC partners on the common threats facing Europe would be a pre-condition. It is far from clear, however, that this condition is met.

The ESC model could therefore better constitute a long-term goal towards which the EPC can move in the further future. But even then, there remain fundamental questions, not least as to its rotating membership and whether, for example, large EU member states would be ready to accept a membership composed of only small and non-EU member states, for example.

A European G20

This is the most likely main model, while potentially including elements of the others. France clearly considers the EPC to be something akin to the G7 or G20 summits but with a broader focus beyond the economic lens. It sees it as an intergovernmental political forum where central topics are discussed at the level of heads of state or government. The Group of Seven (G7) brings together the leaders, and ministers, of seven industrialized countries with advanced economies to discuss common positions on global political questions. The Group of 20 (G20) is composed of 19 of the world’s largest economies, including industrialized nations and emerging markets, and the EU. Both are informal intergovernmental fora without an own administration or permanent representation. The annual summits are organized by the rotating presidencies, which are responsible for the agenda setting and preparations. Summit outcomes can include declarations, reports or work plans.

The meeting of 6 October in many ways already points towards the G7/G20 model for the European Political Community. French and German officials have stated that they have no interest in creating a format with a standing secretariat. That goes for the UK as well. Any suggestion of turning the European Commission into such a secretariat, for example, seems rather unrealistic as does a formalization of the EPC through an EU-EPC treaty as has been proposed. EPC meetings are planned to take place biannually. They are organized and held by a rotating host, alternating between EU country and non-EU country, similar to the G7/G20 summits, but linked with the rotating EU Council presidency.

In the end, it seems likely that in due course the EPC will indeed become a European version of G20, not least because it is the model preferred by France, which has been very assertive in pushing its own ideas. It is also a suitable way to continue to offer what has been lauded as the main achievement of the first meeting, i.e. an opportunity for the attending leaders to engage in frank and open dialogue on politics – and not policy. In addition, a European G20 could absorb some elements of the other models. It can give EU candidate countries a place to discuss common concerns on an equal footing with the rest of the continent while working towards EU accession, but also serve as a forum to bring the UK back to the table in Europe.

This integrated model would, however, not be without challenges. On the one hand, there is the question of whether the EPC could weaken EU authority and EU actions where the areas of activities overlap– something that the EU institutions would not readily accept. On the other hand, the heterogeneity of the EPC’s members as well as the continued existence of other, more relevant fora such as NATO, the ‘real’ G7/G20 or, at a global level, the Conference of the Parties (COP) might make it difficult for the EPC to prevail and survive in the long-term. This risk would further be reinforced if, for example, France loses interest in the project and/or Moldova becomes overwhelmed with the hosting of the second meeting in spring 2023.

Conclusion: from family photo to 'strategic intimacy'

“At the Prague Summit, the family photo is the message,” wrote Kribbe and Van Middelaar on the day before the inaugural meeting of the European Political Community. But a photo with no substance behind it is just an image. If it is to become a meaningful layer of political cooperation in the European security landscape, the EPC has to prove that it can achieve more than just bringing together leaders for yet another photo-op. That means not least which concrete policy outputs it is supposed to bring about. The leaders agreed on a number of priority areas for cooperation (including energy, infrastructure, cybersecurity, regional cooperation in the Black, Baltic and North Seas, and youth) but how these priorities will be funded and their follow-up handled remains to be defined. In Prague, Macron pitched the idea of ‘strategic intimacy’ as an overall goal for the EPC. It now remains to be seen whether this can be achieved in the long-term or indeed whether it is just a vacuous phrase.

It also still remains to be clarified to what extent, in the EPC’s new conception, the EU should be involved considering that the proximity to the bloc remains, as was also demonstrated by the attendance of the Presidents of the European Council and the European Commission. It seems that, in the very least, the EU institutions could play a role – in lieu of a standing secretariat – in assisting in particular small countries with little resources in organizing and hosting the meetings. At the same time, it is clear that the existence of the EPC should not side-line other points on the European agenda such as EU enlargement or the question of how to offer Ukraine access to the single market as was suggested by Commission President von der Leyen in her State of the Union speech. Neither should it encroach upon the competences and fields of action of the Council of Europe, which is and should remain the main defender of human rights on the continent. Instead, if anything, the EU enlargement process should continue with priority while CoE activities should be stepped up given the rising threat to human and civil rights across the continent.