Funding remains the Achilles heel of the EU Green Deal. Europe needs to spend an additional €350 billion on climate action every year until the end of this decade. The bulk of sustainable investment is expected to come from the private sector and the InvestEU programme has been established to leverage private investment through the European Investment Bank (EIB) Group and other public financial institutions. However, overly ambitious target volumes backed by only limited public financial support, and the resultant high levels of leverage, prevent InvestEU from delivering its full potential for achieving the green transition. To plug the green investment gap, InvestEU needs to reduce its leverage, increase its transparency on intermediated operations and be complemented by fresh public spending at EU level to finance transformative investments that fall outside the scope of what public de-risking of private investments can achieve.

Funding remains the Achilles heel of the EU Green Deal. Whereas the US and China provide considerable public spending to incentivise clean technologies, the EU fails to match this support. Using temporary exemptions from EU state aid rules, individual member states have been pumping substantial amounts into climate action. However, they do not all have the same budgetary resources to fund green projects and it is an open question whether sustainable investments will win preferential treatment under the reformed EU fiscal rules. At EU level, the pandemic recovery response NextGenerationEU and the EU’s long-term budget together allocate 30% of EU funds to fighting climate change, but the total sum of €2 trillion is stretched over seven years. Later this year, an EU Sovereignty Fund could see the light of day, but its focus is narrower than boosting green investment and reaching a political agreement will not be easy. For the time being, Europe needs to spend an additional €350 billion on climate action every year this decade to reach its 55% greenhouse gas reduction target by 2030.

EU policymakers have been turning to leveraging private money to plug the green investment gap. In the absence of appropriate funding at EU level, governments’ hopes rest on private funding sources, in particular green capital markets. To mobilise as much as €1 trillion green investment over the period 2021-2027, the von der Leyen Commission in January 2020 launched the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan (SEIP). At its heart is the InvestEU Programme initially proposed in June 2018. It uses public funds and guarantees to reduce the costs and risks for private investors willing to invest in net-zero technologies. InvestEU relies on a multitude of actors with a central role for the European Investment Bank (EIB) Group to achieve its objectives. This leveraging approach could gain more importance in the years ahead as the European Commission proposed raising overall funding for InvestEU when presenting its Green Deal Industrial Plan in early 2023.

How to fund the European Green Deal requires a rethink. In this policy brief, we show how the shortcomings of InvestEU in combatting climate change can be addressed and why it is no substitute for fresh public spending at EU level. First, policymakers need to acknowledge the limits of the leveraging approach. Several important transformative projects fall outside the scope of what public de-risking of private investments can achieve, as these are part of public infrastructure or will simply not be commercially viable. Second, you cannot green the European economy on the cheap. By defining ambitious target volumes without matching them with appropriate funding, InvestEU has a high leverage that prevents it from taking the risks necessary to provide truly additional green investment. To maximise its impact on the green transition, InvestEU should get a funding boost and concentrate on those areas where de-risking works. Third, InvestEU success depends not just on how much but also on how public money is spent. Greater transparency and accountability are needed to ensure that investments are in line with EU climate policy.

1 InvestEU and the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan

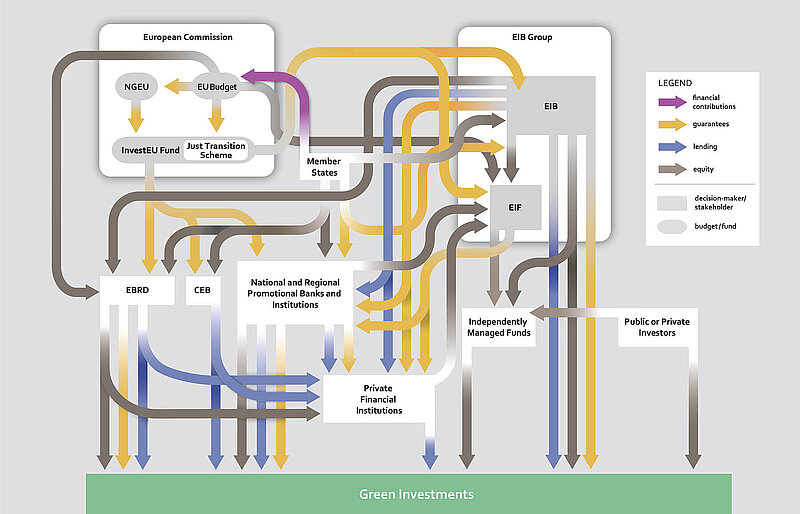

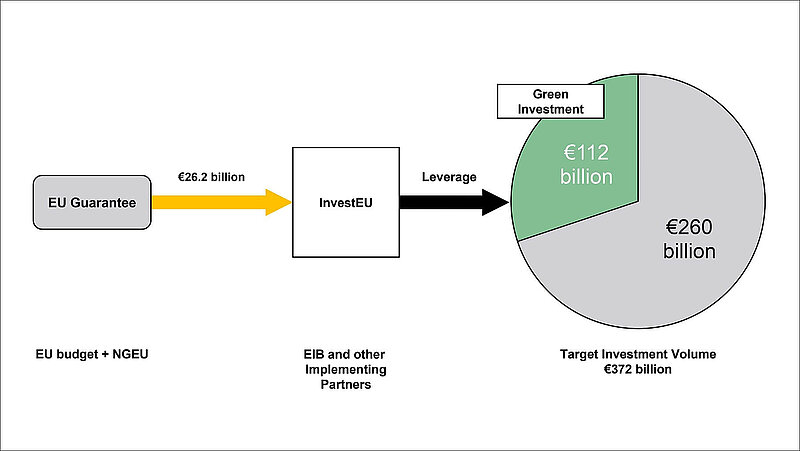

InvestEU is the cornerstone of the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan, the investment pillar of the European green transition. Consolidating several EU financing programs and instruments, InvestEU aims to mobilize more than €372 billion of public and private investments through a €26.2 billion guarantee from the EU budget, which is operationalized by the EIB Group and other public financial institutions. With the overarching goal of supporting “economic recovery, green growth, employment and well-being”, InvestEU supports investments in four policy areas: a) sustainable infrastructure b) research, innovation, and digitalization c) SMEs, and d) social investment and skills. Its financial architecture is complemented by the InvestEU Advisory Hub, a technical expertise facility that helps private and public project promoters prepare their projects and access public financial support. At the time of writing, InvestEU is not yet fully operational, as the European Commission is still in the process of signing guarantee agreements with the so-called InvestEU Implementing partners (see below). Figure 1 shows the sheer complexity of the EU leveraging landscape under InvestEU with the EIB Group at its heart.

Figure 1: The EU leveraging landscape under InvestEU

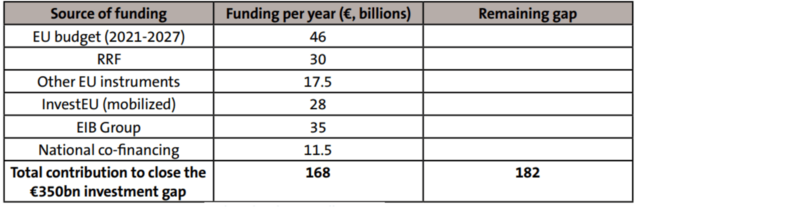

The Sustainable Europe Investment Plan (SEIP) recognizes the massive investment needs of the European Green Deal. Unveiled by the European Commission in January 2020, the SEIP is designed to mobilize €1 trillion of sustainability investments from public and private sources by 2030 and support cohesion territories in realizing the green transition. It bundles together several EU spending programs and instruments dedicated to environmental priorities, but with no overarching governance framework. To assume the role of the SEIP’s main implementation partner and further support the European Green Deal, the EIB Group announced in 2019 it would become the EU's climate bank and double its climate action and sustainability lending by 2025 as well as aligning its financing operations with the goals of the 2015 Paris Accords. The Bank expects this transition to mobilize €1 trillion on top of SEIP. The Commission and the EIB Group, however, underline that the SEIP falls short of closing Europe’s green investment gap. In early 2021, the European Commission and the EIB Group estimated that the SEIP met less than half of the Green Deal’s additional investment needs of €350bn a year. Table 1 shows an outstanding gap of around €182 billion per year.

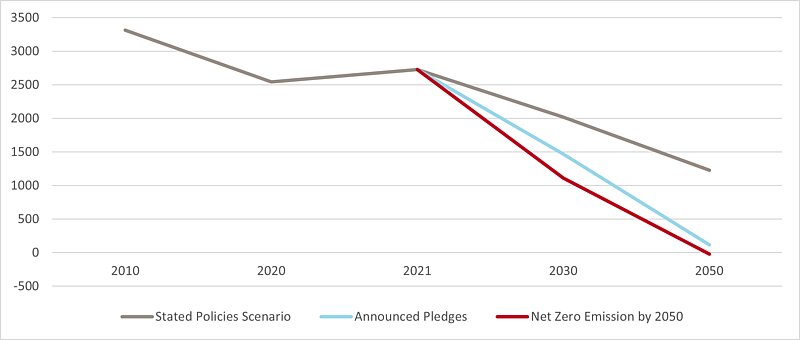

The EU is not on track to fulfil the Paris Agreement. Proclaiming the ambition to become the world’s first climate-neutral region, the EU adopted a legally binding target of carbon neutrality by 2050. However, Figure 2 shows that the measures adopted by the end of September 2022 are not sufficient to achieve this goal and that even the pledges made so far fall short of the Paris Accord commitments. The recent agreement on key pieces of the “Fit-for-55” package, including a reformed emissions trading system (ETS) and a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), represent an important milestone on the EU path to reducing net greenhouse gas emissions. However, investments in Europe’s net zero economy remain an unresolved issue.

Figure 2: EU Total CO2 emissions (Mt CO2) by scenario

To bridge the Green Deal Investment Gap, European policymakers contemplate expanding on the idea of leveraging the financial system through the EIB Group and public financial institutions. This consists in using limited contributions from the EU budget to share risks and unlock co-investments from public and private actors. The Commission mainstreamed this approach with the 2014 European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), which served as a blueprint for InvestEU. EFSI was co-designed with the EIB Group to mobilize capital markets for growth-enhancing investments after the Eurozone crisis and given high levels of debt in several member states. As negotiations for the 2014-2020 Multiannual Financial Framework had already been concluded, the European Commission back then had to find ways to invest without big spending commitments. EFSI differed from traditional lending and public finance in that it relied on complex financial instruments to share risks with public and private investors and create contingent liabilities that did not weigh on the EU budget. In a memorable phrase, then Commission president Juncker explained: "We will have to do more with less. We need to get the best out of the budget and spend money smartly”. InvestEU sets out to replicate this approach.

Leverage under InvestEU is realized in two steps as shown in Figure 3. Leverage refers to the sum total of public and private co-investments crowded in with the EU guarantee or the difference between investment targets and EU budget support. First, notwithstanding meaningful differences between the EIB Group and other financial institutions, the EIB Group raises funds on international capital markets backstopped by the EU guarantee support. In a second step, the Bank deploys these funds either via direct instruments, co-investing with private and public actors in individual projects. An example would be the EIB Group extending a loan to an infrastructure project promoter, performing due diligence on their project preparation and financial structure. Or it relies on indirect instruments that share financial risks with public and private financial intermediaries, such as loan portfolio guarantees, on-lending, or securitizations. The more the Bank relies on indirect instruments the more leverage it can realize, as these blend the EIB Group’s resources with the capacities of public and private banks and private investments.

Figure 3: Leveraging through InvestEU

In a major departure from EFSI, InvestEU brings promotional banks and International Financial Institutions directly into the European financial support and advisory framework. InvestEU provides 75% of its guarantee support to the EIB Group and the remaining 25% to other financial institutions, collectively referred to as InvestEU implementing partners. At the time of writing, the Nordic Investment Bank, Italy’s Cassa Depositi e Presititi, France’s Caisse des Dépôts, and Spain’s Instituto de Crédito Oficial, alongside the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB) had passed a so-called seven-pillar assessment to become implementing partners. InvestEU can sign up other partners at any given point. This assessment process reviews the compatibility of financial institutions’ organizational setups and audit and control procedures with European standards. Further, the project preparation and advisory support complementing InvestEU, the InvestEU Advisory Hub, is open to partnerships with national promotional banks that are not implementing partners. This partnership framework in financing and project preparation is an innovation vis-à-vis EFSI, which had supported EIB Group operations alone and whose advisory services (the European Investment Advisory Hub and the European Investment Project Portal) were and are managed only within and by the EIB Group.

InvestEU is governed by the European Commission. Whereas EFSI gave full operational control to the EIB Group with the EFSI steering board located within the Bank, the Commission oversees InvestEU and its investment decisions through its steering and policy boards, which tailor and approve financial assistance, and assesses the economic viability and policy alignment of support applications through the Brussels-based InvestEU secretariat. Once approved by the secretariat, InvestEU implementing partners review the structuring and risk profile of the application and refer these to the independent investment committee. Partners cannot assess applications they have themselves submitted. The InvestEU Regulation requires the European Commission to show InvestEU's contribution to the Green Deal and climate tracking information now also covers SME-related investments that make up 45 % of the portfolio. Taken together, the standards for accountability and transparency have substantially improved compared to EFSI.

2 The limits of InvestEU and the leveraging approach

InvestEU learns important lessons from EFSI, but its high leverage risks misaligning European financial support with the implementation of the European Green Deal. InvestEU steps up collaboration between the European Commission, EIB Group, member states, and promotional banks to expand access to the financial and advisory opportunities provided with European resources. The limited public funds undergirding InvestEU, however, create a tradeoff with its capacity to crowd in transformative investments and share risks and rewards between private investors and the European public.

2.1 InvestEU should be complemented by fresh public EU spending

Some sectors and projects that are critical to the green transition are not suitable for InvestEU financing. InvestEU and its implementing partners can crowd in private finance for low-risk green projects at scale, including for those projects that on their own would be too small and bespoke to attract private investments. However, there is infrastructure that is important to the green transition but that is in public hands. To give an example, the power grid in Europe is largely public and state-owned companies dominate EU railway markets. What’s more, there are projects that are important to the green transition but that will not generate any monetary profit at all. Since these projects will never be commercially viable, private investors will not finance them even if supported by InvestEU. Therefore, leveraging private investment with public money will not suffice to fund investment in all areas needed for a clean energy economy. Here, direct public funding is required.

InvestEU should be complemented by fresh public EU spending. Policymakers need to acknowledge the limits of the leveraging approach. InvestEU is no substitute for fresh public spending at EU level. The Sustainable Europe Investment Plan should be based on a realistic assessment of the contribution that InvestEU and private finance can make to the green transition. All projects that cannot be financed by InvestEU and the private sector require direct public funding. InvestEU should, therefore, be complemented by fresh public spending at EU level to finance the transformative investments that fall outside the scope of what public de-risking of private investments can achieve. Only then the EU has a chance to reach its climate targets.

2.2 Reduce leverage through more funding for InvestEU

InvestEU’s high leverage delimits its ability to mobilize the transformative investments envisioned by the Green Deal Industrial Plan. As currently designed, InvestEU is effective in unlocking investments for projects with a lower risk profile, such as energy efficiency retrofits of real estate, as it shares financial risks with investors and deploys advisory capacities to support project promoters with structuring their projects and feeding these into a broader green pipeline. This capacity is in line with EFSI, which proved highly successful in unlocking green investments and creating a pipeline of bankable projects. However, InvestEU shares also EFSI’s flipside of a high leverage that it will mostly support projects that yield sufficient cash flows in the short-to-medium term. This is because implementing partners are likely to prioritize indirect instruments to realize InvestEU’s target volume such as loan guarantees, which increase the balance sheet and lending capacities of private intermediaries. Indirect instruments, however, depend on cooperation from private intermediaries and investors for implementation and lengthening investment chains limit the Commission’s ability to tie financial support to conditionalities or performance criteria. These instruments contrast with (green) industrial policy instruments, such as grant funding for innovative low-carbon technologies from the EU’s Innovation Fund, as these give the Commission direct control over funding decisions, performance-related conditionalities, and the sharing of risks and rewards.

Future-oriented sustainability investments as envisioned by the European Green Industrial Plan are commercially viable only in the longer run as they are surrounded by high technological uncertainties, including construction risks. These include research, development and innovation in battery technologies, critical raw materials refining and recycling, demonstration plants for manufacturing materials in the supply chain of electric vehicle batteries, hydrogen propulsion technologies, innovative advanced biofuels plants, or advanced manufacturing technology equipment in steel processing. InvestEU can help mobilizing private investments for these types of projects but this will require equity investment from InvestEU implementing partners to share risks and rewards and enforce performance-related conditionalities. And a different class of transformative projects, importantly climate adaptation projects, will require grant support accompanied by loans as these are commercially unviable on their own in the longer term. InvestEU’s high leverage, in short, limits Implementing Partners’ capacity to turn innovative projects with transformative potential into propositions for private and market-based finance as it limits their capacity to provide direct and balance-sheet-intense support.

The implementation of EFSI highlighted the difficulties of unlocking transformative investments with indirect financial instruments. In mobilizing investments, the EIB Group had to reconcile EFSI’s investment targets with the limited guarantee support it received and its own corporate governance. This led the Bank to rely on complex financial instruments and risk-sharing with financial intermediaries to maximize public and private co-investments. If the tradeoff between investment volume and economic risk-sharing was less of a problem in earlier years—EFSI was conceived as a countercyclical response to the financial and Eurozone crises—, it constrained EFSI’s ability to support higher-risk investments and the implementation of the 2015 Paris Accords. Many commentators, including the European Court of Auditors, have criticized the limited additionality of EFSI, its inability to unlock projects that were too risky from a private finance perspective. The issue was compounded by the political pressure the EIB Group was under to reach EFSI’s targets. As the pipeline for higher-risk investments remained limited, the Bank used EFSI-supported instruments for high-risk investments, such as first-loss tranches, and also for enhancing the financial conditions for mature infrastructure projects. This led member states and national promotional banks to raise concerns about the EIB Group encroaching on national promotion.

The Sustainable Europe Investment Plan should reduce leverage by providing more guarantee support and capitalization to InvestEU Implementing Partners, while continuing to pursue ambitious climate policy objectives. The EU’s public promotional bank field provides one of the strongest institutional frameworks for guiding private investments towards mission-oriented and transformative policies. More support would allow the EIB Group to make more direct investments and harness its risk management and project preparation expertise. And more funding for InvestEU would create more scope for implementing partner and promotional banks to blend EIB Group capacities, including in member states with limited experience in public investment banking. At the same time, increased capitalization would help promotional banks green their portfolios and manage the losses associated with fossil fuel disinvestment. While member-state contributions to national promotional banks and InvestEU instruments will play an important role, more funding for InvestEU will increase Europe’s opportunities scope for making transformative investments. This would also hedge against the risk that member states further diverge economically carried by of state-aid and member-state solutions, as proposed by the Net-Zero Industry Act.

2.3 Improve accountability on InvestEU’s climate impact

A lack of transparency makes it difficult to track whether investments are in line with EU climate policy. The InvestEU Regulation requires the European Commission to show its contribution to the Green Deal. However, as criticised by the European Court of Auditors, the reporting arrangements for InvestEU do not include the actual climate and environmental results of any projects it supports. Furthermore, the amounts of InvestEU financing tracked in accordance with the EU green taxonomy are not disclosed. Beyond these conceptual weaknesses, the European Commission in practice has so far failed to publish data through its climate tracking system as required by law. What’s more, many documents are kept confidential and even the published ones rigorously protect clients’ commercial confidentiality. As a result, it is difficult to verify InvestEU’s climate impact and to scrutinise where the intermediated money ends up — let alone establish whether or not the EU lives up to the climate policy leadership role it lays claim to.

InvestEU must become transparent on benefits delivered. To ensure that public funding is conducive to the public good, the institutions involved in InvestEU need to raise the bar on transparency. In concrete terms, the Commission should disclose how much InvestEU financing is tracked using the EU Taxonomy and report on the climate-related results, such as actual cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, of its financing operations. As for the EIB Group, a detailed set of recommendations endorsed by 53 organisations point to some immediate steps that could be taken.

3 Conclusion

InvestEU deserves an overhaul to maximise its potential for financing the European Green Deal. Under the Green Deal Industrial Plan, the European Commission proposed increasing funding for InvestEU. As shown in this Policy Brief, funding is not the only shortcoming that should be addressed to better deliver on EU climate goals, but it is an important one. With the aim of preserving the public sector’s role as a catalyst for the green transition, it is vital to de-leverage InvestEU to allow for direct financial instruments such as grant funding for innovative low-carbon technologies that are not bankable. This requires additional funding for InvestEU as proposed by the Commission. However, to ensure that InvestEU provides extra value added for European taxpayers and supports the green transition, the institutions involved need to raise the bar on transparency. Since certain investments that are important for a clean energy economy lie outside the scope of private finance, InvestEU should be complemented with fresh public spending at EU level.

The investment pillar of the European Green Deal should leverage the full potential of Europe’s promotional banking field for the green transition. For more than a decade, green investment enjoyed very low lending rates via an accommodative monetary policy. As the era of extremely low interest rates has come to an end, the role of public support for sustainable investment is growing in importance. The EU should therefore expand collaborations with national and subnational promotional banks to support the implementation of the European Green Deal. And the investment pillar’s architecture should be streamlined as recommended by the European Court of Auditors. In this way the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan could expand support for cohesion regions and provision against member state divergence. Once first data about InvestEU investments become available, it will be the right moment to make a holistic assessment of the EU’s public investment landscape and investigate how to improve it.