The European audit market has been broken for far too long. After glaring audit failures in the recent past, the legislation is once more under review. Fixing the persistent shortcomings will require serious reforms in three areas. To increase competition and rein in the dominant position of the Big Four, joint audits including at least one challenger firm should become mandatory. Auditors should be prohibited from providing their audit clients with consulting services to eliminate conflicts of interest. And the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) should directly supervise the biggest audit firms to ensure effective oversight. With bold and binding tools, European decision-makers can finish the job and finally turn the EU audit market around.

For the full text including citations, download the PDF above.

Executive summary

The European audit market is broken. When the global financial crisis revealed substantial weaknesses at some large financial institutions, also the audit firms that had provided them with ‚clean‘ bills of health were pilloried. The subsequent EU reforms targeting the financial sector did not forget the audit profession. But extensive lobbying efforts by EY, KPMG, PWC and Deloitte – the Big Four audit firms – prevented serious change. While the measures adopted in 2014 were a

step in the right direction, they failed to achieve the main objectives: greater competition, reinforced professional scepticism, and restored confidence in companies’ accounts.

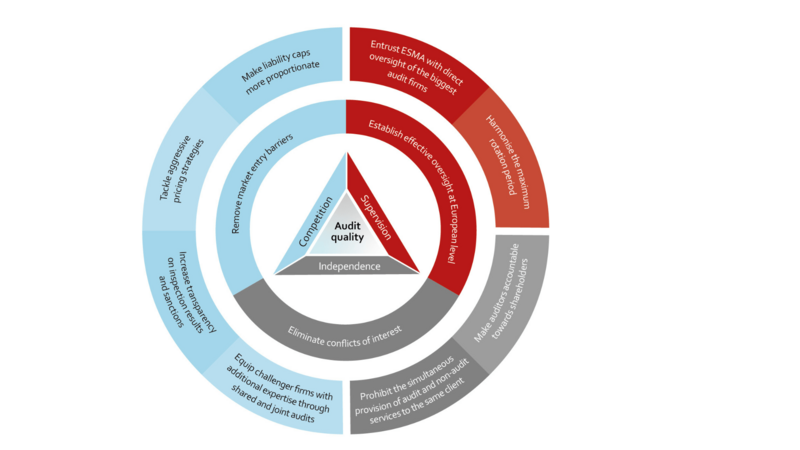

Concentration of market power at the Big Four, impaired auditor independence, and inadequate public oversight continue to undermine audit quality. These shortcomings are particularly pronounced at the top end of the audit market, where public interest entities (PIEs) suffer from a lack of choice. To strengthen audit quality, this paper argues that bold and binding measures are necessary in the following three areas:

First, the barriers that currently hinder challenger firms, i.e. Non-Big Four audit firms, from entering the market should be removed. To equip smaller audit firms with the expertise needed for the audit of large companies, the EU should require PIEs to engage at least one challenger firm as shared auditor and, after a transitional period, as joint auditor. In addition, all national audit supervisory bodies should offer complete transparency on inspection results and sanctions. Moreover, aggressive pricing strategies undermining audit quality should be tackled head-on and liability caps currently discriminating against smaller audit firms should be made more proportionate. Taken together, these measures would boost challenger firms‘ ability to compete with the Big Four.

Second, remaining conflicts of interest should be eliminated. The easiest way to strengthen auditor independence is to prohibit audit firms from providing their PIE audit clients with non-audit services. Furthermore, to curtail the company management’s influence, auditors should be required to present their findings at annual general meetings and answer questions raised by shareholders.

Third, public supervision of the audit profession should be beefed up. The biggest audit firms should be directly supervised by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) to ensure effective oversight at European level. Finally, the application of the European rulebook should be further harmonised across member states to meet the goal of a Capital Markets Union.

After some glaring audit failures in the recent past, the EU audit legislation is once more under review. The European Commission has staged a public consultation and is set to publish its legislative proposals in early 2023. This time, Europe needs to finish the job and adopt bold and binding measures. With the right tools, political decision-makers can finally turn the market around.

This policy paper is part of the “Visions for Europe” series that develops longer-term visions and recommendations for different EU policy areas. It is based on extensive consultation with experts and stakeholders from the national and European level, including a closed workshop held in June 2022 in Berlin. The views and opinions expressed in this policy paper are solely those of the author.

1 Introduction

Europe’s market in auditing large companies is broken. Deloitte, EY, KPMG, and PWC together dominate the statutory audit market of public interest entities (PIE). High concentration of market power at the Big Four firms, impaired auditor independence, and weak public oversight are undermining audit quality. This is problematic because statutory audit, alongside corporate governance and supervision, is meant to provide assurance that financial statements give a true and fair view of companies’ financial health. This assurance is key to financial stability as market participants rely on trustworthy information.

The EU audit market rules adopted in 2014 have not achieved their goals. In the wake of the financial crisis, the European Commission proposed far-reaching reforms to increase competition, reinforce professional scepticism, and restore confidence in companies’ accounts. However, after intense lobbying, only a few of the ambitious reform proposals finally became law. Since then, neither market concentration nor auditors’ dependence on their clients have decreased noticeably, while multinational audit firms are still not properly supervised at EU level. After prominent audit failures in the recent past, the legislation is once more under review. The United Kingdom has launched a radical process that will shake up the market there. On this side of the Channel, the European Commission is set to issue legislative proposals for the EU in early 2023.

To remedy the persistent shortcomings, the EU audit market rules must undergo a profound overhaul. The disappointing results of the last round of reforms underline that minor tweaks and mere incentives are not enough on their own to break the dominance of the Big Four and improve audit quality. Instead, the EU should adopt bold and binding measures in three areas. First, market entry barriers should be removed to allow challenger firms to compete with the Big Four. Second, remaining conflicts of interest should be eliminated so as to strengthen auditor independence. And third, audit firms should be subject to effective oversight at European level.

2 Shortcomings in the European audit market

Auditing is of crucial importance for the functioning and stability of financial markets. It forms the backbone of trust between business and society. However, lack of competition, independence and public oversight are impairing the proper functioning of the EU audit market. This chapter explains the importance of robust audits and outlines shortcomings in the PIE audit market and their origins.

2.1 The importance of robust audits for financial stability

Confidence in the veracity of financial statements is crucial for financial markets to function. By verifying companies’ annual accounts, auditors reduce the risks of misstatement and thus build confidence in companies' numbers. This additional assurance of reliable and trustworthy information benefits a wide range of stakeholders. Accurate financial statements are crucial for shareholders, investors, banks, credit rating agencies, and trading partners. If they cannot trust these financial statements, they charge a risk premium. This raises the costs of capital for companies, leads to fewer investments and – ultimately – to higher prices for consumers. Employees, too, depend on auditors’ provision of a realistic view of their firm's financial health to know whether they should remain with their current employer or rather look out for a new job. Last but not least, public authorities rely on correct financial statements for tax calculation and other purposes. The fact that auditing is a service provided in the public interest is demonstrated by recent accounting scandals such as Carillion, Wirecard, and Thomas Cook which have cost investors billions of euros, undermined basic trust in corporate reporting and shaken the stability of financial markets.

The importance of sound financial statements is reflected in the legal requirement for certain companies to have their accounts audited. In the EU, medium-sized and large undertakings as well as public interest entities (PIEs), i.e. banks, insurers, listed companies and those specifically designated as such by member states, are obliged to have a statutory audit.The provision of statutory audits is regulated by the EU Audit Directive.Only natural persons (statutory auditors) or legal persons (audit firms) approved by the competent national authorities are allowed to perform statutory audits. For PIEs, the EU Audit Regulation foresees stricter requirements because the potential negative consequences of misstatements are usually greater than for other types of undertakings.

2.2 Factors undermining top audit quality

The credibility of audit opinions depends crucially on their perceived quality. If stakeholders do not trust the auditor to thoroughly assess the company’s books and report on material errors, the audit opinion will be meaningless. Three factors currently undermine the quality of auditing services in the EU: high market concentration, impaired independence, and weak public supervision. Spectacular accounting scandals have exposed blatant audit deficiencies, but evidence from audit oversight bodies shows that poor audit quality is a broader problem.

2.2.1 High market concentration

The European audit market lacks competition. In a well-functioning market with genuinely competitive forces at work companies can pick and choose among a multitude of auditors and select the one that corresponds best to their preferences on price and quality. Where the audit firm does not meet clients’ expectations, it must fear negative consequences for its reputation and risks losing other clients or failing to win any new engagements. At the top end of the European auditing market, however, this is not the case.

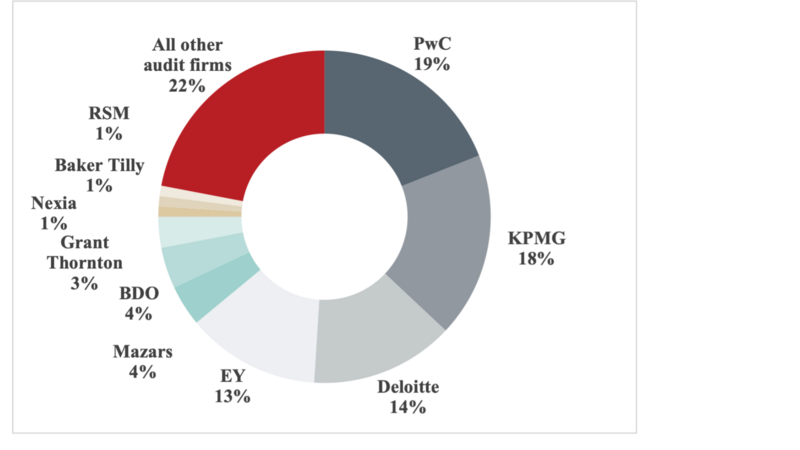

Since the 1980s, the audit market has become increasingly concentrated. Between 1986 and 2002, the number of large audit firms worldwide decreased from eight to four. Since then, the Big Four have dominated the global market. In Europe, PWC, KPMG, Deloitte and EY together held about two thirds of the aggregated market of PIE statutory audits in 2018 (Figure 1a). Looking at revenue from PIE audits, the Big Four with over 90% of total revenues are even more dominant (Figure 1b). Research shows that this level of market concentration can seriously undermine competition and audit quality.

Figure 1a: EU market share (2018) as measured by number of PIE statutory audits

Figure 1b: EU market share (2018) as measured by revenues

The high concentration in the PIE audit market is a result of persistent market entry barriers for smaller audit firms. Since 2016, PIEs must change their external auditor at least every ten years. However, for the rotation requirement to have a positive effect on competition, there must be enough challenger firms willing and able to take on a mandate when it becomes free. But several barriers prevent smaller audit firms from entering the market for audits of large companies.

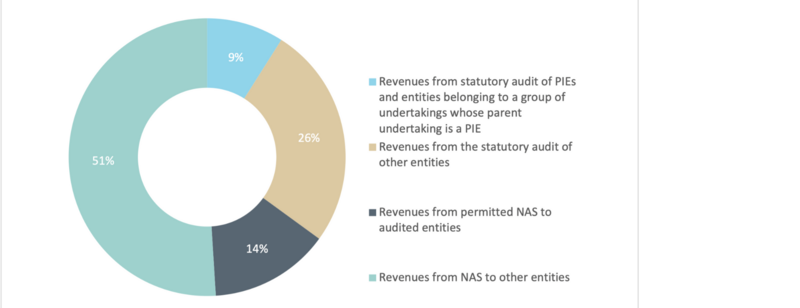

The Big Four benefit from economies of scale. Technical progress, new audit methods and complex audit engagements require personnel and financial resources as well as sector-specific knowledge. However, small and medium-sized auditors often lack the necessary human resources and professional skills to audit PIEs. In many cases, they cannot satisfy the demand of multinationals to have all their subsidiaries audited according to the same standards. And, they lack sector and industry experience which many clients associate with superior audit quality. Last but not least, the Big Four generate a significant portion of their income from non-audit services that they offer either to the same audit client (permitted NAS) or to other companies (NAS). These highly profitable services provide them with a competitive advantage over smaller audit firms that often cannot afford to join in the costly audit tenders of large companies (Figure 1b).

Auditing is a credence good. The audit process is largely unobservable which makes it difficult for outsiders to distinguish between good and bad audits. In this situation, large audit firms benefit from the fact that they typically have a higher reputation than smaller firms in terms of experience, expertise, know-how and industry knowledge. PIEs often feel they cannot trust smaller audit firms to perform complex audits and therefore prefer to choose a renowned auditor – one of the Big Four firms. Confidence in their work is so high that cases have been reported where a bank would not grant a loan if the company had its accounts audited by a smaller audit firm.

Aggressive pricing strategies keep challenger firms out of the market. To obtain a new audit engagement, audit firms often agree to price cuts which they then try to overcompensate through fee increases in the further course of the business relationship with the same client. If the audit fee discount offered is so big that fees are below-cost, this pricing strategy is referred to as low balling.This is a problem for fair competition. Deep-pocketed Big Four firms are in a better position to engage in low balling to win mandates, thus keeping the small fry out of the market. Initial discounts can also impair audit quality. If auditors do not manage to extra-bill clients at a later stage, they might decide to reduce the audit workload so as to avoid making a loss – but to the detriment of audit quality. In addition, low balling is putting the auditor’s independence at risk. To retain the mandate until at least break-even point, the auditor might be prone to cover up discovered misstatements.

Meaningful regulatory measures come with side effects that restrict competition. For one thing, audit firms are subject to an internal rotation obligation after which the auditor in charge must be replaced. While this makes sense to reduce the risk of becoming captured (“familiarity threat”), it often forces smaller audit firms to resign from a mandate, as they often lack the staff to replace an auditor internally. Furthermore, auditors may not earn more than 15 percent of their total income from one PIE client. While this provision strengthens the auditor’s independence, it also prevents small audit firms with fewer clients from competing for PIE engagements as these would quickly push them over the 15 percent threshold. Finally, liability limits may keep smaller audit firms out. When auditors face civil liability for their actions, they have an added incentive to audit companies properly and diligently. However, liability levels in EU member states are often so low that they neither cover the damage caused nor act as a deterrent for large firms. For smaller firms, on the other hand, the liability limits tend to be too high, because even slight negligence can cause considerable damage and swiftly threaten the auditor's very existence. Consequently, it is often not profitable for challenger firms to bid for a PIE audit.

As a result, audit clients suffer from a lack of choice. If they are dissatisfied with their incumbent auditor, PIEs are merely thrown back on hiring another Big Four firm. This might explain why reputation effects also seem to be limited: Renowned audit firms can count major accounting failures among their clients, but their market shares have remained rather stable over the last decade. This is a competition issue. If the Big Four can retain their market shares even if involved in high-profile scandals, they might be inclined to cut corners on quality so as to save costs and maximise profits.

2.2.2 Impaired auditor independence

The audit of financial accounts poses several risks of conflict of interests. Independence is the “unshakeable bedrock of the audit environment”. Only an independent auditor will report any material errors discovered in the accounting system. However, auditors are paid by the firm they audit (“auditee selects and pays the auditor” problem). This can create incentives to please the client by skating over identified shortcomings in the audit report. Auditors’ professional scepticism is especially at risk where they provide their audit clients with other services such as working capital opinions, comfort letters on tax or on financial policies and procedures. In the EU, audit firms that audit PIEs generate 14% of their revenue from legally permitted non-audit services (NAS), see Figure 2. So, they have a natural interest in avoiding actions that could upset their audit clients.

Figure 2: Revenue breakdown of firms auditing PIEs (2018)

2.2.3 Unsatisfactory public oversight

Weak supervision of audit firms invites moral hazard. If effective, public oversight provides strong incentives for audit firms to abide by the rulebook. However, in many EU member states this is not the case. Following the failure of Wirecard, an advisory body to the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) warned that “the current organisation of public oversight of statutory auditors and audit firms in European Member States is fragmented and overly complex, characterized by limited responsiveness to red flags”. In the same vein, the European Commission found substantial variations among national competent authorities (NCAs) when it comes to measuring systemic risks, i.e. risks arising from a high incidence of audit quality deficiencies. By law, NCAs must regularly carry out quality assurance reviews at audit firms auditing PIEs. However, lacking financial and human resources, NCAs often contract external experts from the Big Four which raises concerns regarding the independence of supervision.

A lack of transparency and effective European oversight compromises market discipline. Hardly any EU member state discloses findings and conclusions on individual inspections. In most cases, NCAs fulfil their transparency requirements by publishing annual activity reports that contain only aggregated information on inspections. Furthermore, the common rules are rarely enforced. 60% of NCAs in the EU reported that they had not imposed any sanctions as a result of the findings made in the period 2017-2018. Where NCAs do apply sanctions, they tend to be low and the identity of the sanctioned statutory auditor or audit firm is not disclosed, so that investors and business partners are unaware of any wrongdoing. Finally, as the supervision of audit firms remains in the hands of national authorities, firms offering their services internationally are not properly supervised at European level.

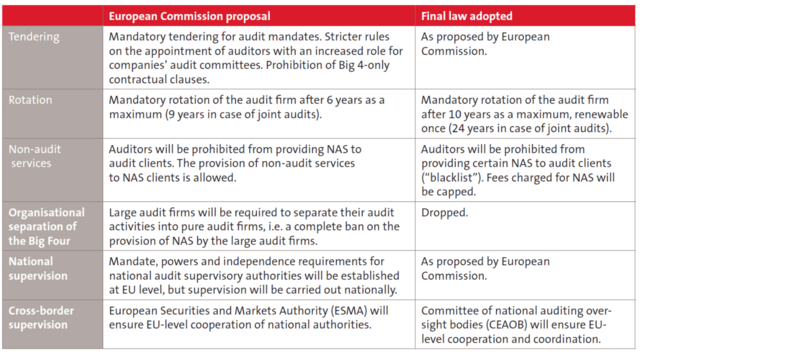

3 The EU audit reforms adopted in 2014 have had limited impact

The weaknesses facing the EU audit market are not new. The financial crisis of 2007/2008 raised serious questions regarding the quality of PIE audits. Auditors had provided several large financial institutions with 'clean' audit reports just before the crisis revealed substantial weaknesses in their financial health. Subsequent inspections confirmed audit quality issues in major audit firms.Therefore, EU Commissioner Michel Barnier in 2011 proposed fundamental reforms to the European audit system. His proposals were far-reaching but most of them did not survive the legislative negotiations (see Table 1).

Table 1: 2014 EU audit market reforms

As a result, the audit reforms agreed in 2014 were only half-hearted. The most important changes for PIE audits included mandatory rotation every ten years (up to 24 years for joint audits), a ban on providing certain non-audit services to audit clients, limitations on the fees charged for non-audit services, and a loose coordinating role for the Committee of European Auditing Oversight Bodies (CEAOB). These measures were a step in the right direction. However, the longer rotation period for joint audits was not enough to incentivize joint audits in countries beyond France where joint audits are compulsory for all PIEs. The CEAOB now facilitates cooperation between national auditing oversight bodies but lacks the mandate to directly supervise or sanction individual audit firms. On top of this, the rules contain several options allowing individual member states to modify the blacklist of prohibited NAS or the maximum rotation period. As a result, there is no EU-wide set of rules.

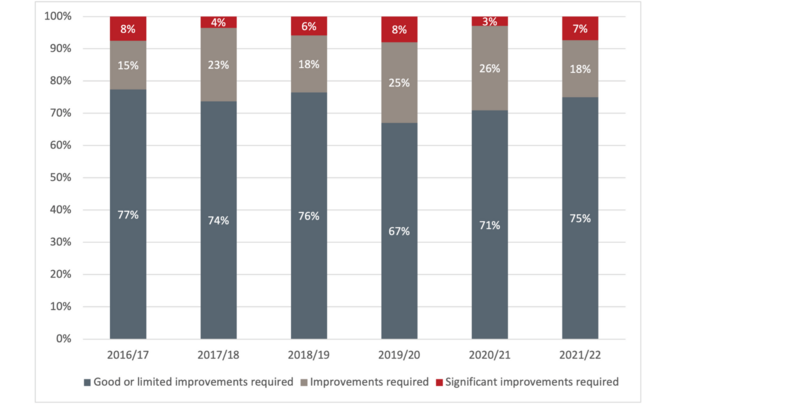

Audit quality continues to be a concern. In 2017, the Dutch financial market supervisor AFM made clear that “(…) the quality of the inspected statutory audits by the Big 4 audit firms is still not satisfactory. It is essential for the proper functioning of the capital markets that the auditor’s opinion is beyond doubt”. In the same vein, the European Commission in 2021 alluded to structural quality deficiencies in PIE audits across the EU.The most recent data comes from the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) in the United Kingdom (UK), which is one of the rare authorities to regularly disclose the results of audit quality inspections in specific audit firms.Given that the UK market and regulatory environment closely resembles that of many EU member states, the results are also telling for the EU. In the last round of inspections (2021/2022) comprising the largest seven audit firms in the UK, the FRC found that as many as 25% of the inspected audits required improvements or significant improvements (Figure 3).

Figure 3: FRC inspection findings at the largest audit firms in the UK

4 How to turn the European audit market around

Addressing persistent issues in the audit market requires bold measures. It is therefore high time to complete the reform agenda started in 2014 and finally get to the root of the problem. To turn the European audit market upside down, three things must change:

1 .Remove market entry barriers

2. Eliminate conflicts of interest

3. Establish effective oversight at European level

Figure 4: Determinants of Audit Quality and how to improve it

4.1 Remove market entry barriers

The EU needs a competitive auditing environment that allows challenger firms to enter the market, grow enough to exploit economies of scale and provide clients with high quality audit services. This requires the EU to take steps on four fronts.

4.1.1 Equip challenger firms with additional expertise

A gradual approach is needed to increase competition without endangering audit quality. To enable challenger firms to participate in PIE tenders, they must be equipped with additional experience and specific industry knowledge. The only way smaller audit firms can gain expertise is on the job. However, making smaller audit firms (solely) responsible for the audit of large and complex companies could damage audit quality as they sometimes lack the human resources and professional skills necessary to audit PIEs. Instead, a more gradual approach is needed. The involvement of challenger firms in the audit of PIEs should become “managed”, i.e. legally required, and eventually step up from shared to joint audits (for a comparison between the two, see Box 1).

Box 1: Shared and joint audits

In a shared audit, the so-called primary auditor has full responsibility and liability for the financial statements to be audited and for issuing the opinion. The other firm involved, the shared auditor, is responsible for specific areas of the audit and works with the lead auditor. A managed shared audit is a legally prescribed shared audit that must include at least one challenger firm.

In a joint audit, two or more auditors together conduct the audit and jointly certify the audited financial statements of a company. The joint auditors mutually agree on the scope and allocation of the audit work, either by subject matter, by business area or by geographical region. At the end of the audit, the other side performs a cross review of the outcomes. The final audit opinion is based on the judgements of both auditors who share mutual liability for the entire audit. In the literature, there is no fixed term yet for a legally prescribed joint audit that must include at least one challenger firm, but it could – in analogy to managed shared audits – be referenced as managed joint audit.

In the short term, the EU should introduce managed shared audits. With the next tendering of their statutory audit, all PIEs in the EU should be required to appoint a Non-Big Four audit firm to conduct at least 10% of the audit. Such a managed shared audit regime would mirror the recent proposals of the UK government. Through their mandatory involvement in the audit of the largest companies, challenger firms could gain experience, specific industry knowledge, and develop their reputation. However, there is a risk that in managed shared audits Non-Big Four audit firms remain in the role of the "junior partner" and the Big Four continue to audit the more complex areas of a company. Consequently, challenger firms bidding in sole PIE audit tenders could easily concentrate on smaller engagements and the top end of the audit market would not necessarily become more diverse. Therefore, the EU should not stop at managed shared audits.

In the medium term, the EU should require managed joint audits. Once challenger firms have gained expertise in the shared audit of large companies, e.g. after a transitional period of ten years, the EU should ask all PIEs to appoint at least one challenger firm as joint auditor. Managed joint audits guarantee challenger firms work on an equal footing with the Big Four and offer added value resulting from the four-eyes principle and joint responsibility (see Box 2). Joint audits’ positive contribution to competition and quality was already acknowledged in the EU audit reforms of 2014 that extended the mandatory rotation period for joint audits. However, those incentives failed to substantially increase the use of joint audits across EU member states. This time, Europe should do better and adopt a mandatory requirement for joint audits, including the use of challenger firms.

Box 2: Evidence on joint audits

The International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) estimates that joint audits can be found in 55 jurisdictions where they are either permitted on a voluntary basis, or required by law, or required for entities in specific industries or sectors. France is the largest economy to require joint audits for all listed companies (since 1966) whereas Denmark foresaw joint audits for all listed companies from 1930 to 2005.

The French auditing standard on joint audits, NEP-100, is said to be the most detailed and advanced. It sets out high-level requirements for balance in the allocation of work, for each auditor to assess audit risks and the control environment, and to perform critical reviews of the work carried out by the other firm. The precise definition of responsibilities and the balanced work allocation are cited as the predominant reason why the joint audit regime has proven successful in France while it eventually flopped in Denmark.

Regarding joint audits’ effectiveness and efficiency, two recent studies based on interviews with practitioners come to very different conclusions. A survey among 37 German audit committee chairs states that joint audits could increase audit fees by 20% without improving quality. Although predicting knowledge transfer that would improve the competitive position of challenger firms, the study concludes that joint audits bring no efficiency gains. In contrast, another survey conducted among 35 practitioners, regulators, and audit committee chairs based in France, Germany and the UK suggests that joint audit arrangements make a positive contribution to audit quality thanks to the cross-review, task rotation, and enhanced independence and professional scepticism.

As far as costs are concerned, a joint audit is not a double audit, where the entire audit is carried out twice. Still, the coordination between the two auditors and the review of each other’s work do lead to an increase in audit fees. Conclusions drawn from academic and other analyses on the effect of joint audits on audit fees have been mixed, ranging from no significant differences to increases above 25%. However, the additional costs incurred by audited companies can potentially be offset by a lower cost of capital, because investors would have higher levels of confidence in the audited financial statements.

As for market concentration, the French audit market seems somewhat less concentrated than other European markets when considering the number of clients. However, the percentage of fees captured by the Big Four in France is nonetheless quite like that in other countries, suggesting similar market concentration. This result might be due to the fact that France does not require the involvement of a Non-Big Four audit firm in joint audits. Consequently, a significant proportion of joint audits in France involve either two Big Four firms or one Big Four firm and Mazars. Over the period 2002-2017, French firms tended to select more Big Four firms, probably because challenger firms so far lack the resources to perform PIE audits.

The introduction of managed shared and later managed joint audits at EU level would provide the push needed to solve a chicken-and-egg problem. The prospect of a more open market would allow smaller audit firms to make investments in their own capacities and capabilities, thereby strengthening their competitive position. As a result, some challenger firms should be able to grow and exploit economies of scale that currently benefit only the Big Four firms. Taken together, these measures could diversify the market whilst contributing to higher audit quality.

4.1.2 Increase transparency on inspection results and sanctions

A lack of transparency in the European audit market is another entry barrier for challenger firms. Most national auditing oversight bodies in the EU publish only aggregated results of their inspections without disclosing their findings on individual firms. This is also true for sanction reporting where the sanctioned auditor often remains unidentified. The absence of publicly available information helps the Big Four to maintain their reputation advantage. At best, clients can evaluate the quality of an audit firm after several years of a business relationship. Lacking reliable information on the quality of smaller audit firms, companies often prefer to play it safe and hire one of the Big Four firms that enjoy a good reputation.

To reduce that reputation advantage, all national competent authorities in the EU should be required to publish the results of their inspections at firm level and the names of sanctioned statutory auditors and audit firms. This information would help companies’ shareholders and audit committees to make better informed decisions. The additional transparency would also strengthen auditors’ incentives to abide by the rules and invest in improving the quality of their work. These transparency measures would bring the EU up to the standards already applied by the FRC in the UK or the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) in the US.

4.1.3 Tackle aggressive pricing strategies

Unlike members of other liberal professions, such as lawyers, the amount of the auditor's remuneration is not subject to comprehensive professional regulations. The audited company and the auditor are therefore free to agree on the auditor's fee. While price competition is welcome, it must not lead to large players exploiting their dominant position to exclude small providers from the market or to lower quality. To prevent low balling practices that might distort competition and damage audit quality, there is no need to introduce a minimum fee scale. Instead, it would be sufficient to prohibit audit firms from charging artificially low fees in the first year of any mandate.

The initial audit is always more costly for the auditors, who must make themselves familiar with the client's business and processes. With an honest calculation that does not focus on retaining the client, the initial audit cannot be cheaper than the following ones. Instead, first year audits should always be priced with a premium that compensates for the higher audit effort associated with them. Therefore, the EU Audit Regulation should require that the fee for initial audits of PIEs may not be lower than the average of the first three years. This would help not only challenger firms seeking to enter the market. It would also benefit audit teams at the Big Four who struggle with tight budgets that create time pressure and force them to accept doubtful audit evidence and higher audit risks.

4.1.4 Make liability caps more proportionate

Apart from a Commission Recommendation dating from 2008, there are no binding rules on auditor liability at EU level. As a result, national liability regimes vary considerably and the liability limits in many member states tend to discriminate against smaller auditors. Given this, the EU should require member states to link auditor liability caps to the turnover of the respective audit firm. Proportionate liability limits would remove market entry barriers for small auditors and at the same time increase the incentives for the Big Four to audit diligently.

4.2 Eliminate conflicts of interest

The reforms adopted in the EU in 2014 strengthened auditor independence but left a weak spot. Mandatory audit firm rotation reduces familiarity threats associated with long tenures. The establishment of a list of prohibited non-audit services (NAS) for statutory auditors eliminates the risk that auditors audit their own consulting services. And the limits on the fees that auditors can charge for permitted NAS reduce the financial reliance on audit clients. However, the simultaneous provision of audit and NAS to the same company is still allowed. This remains a potential source of conflicts of interest and an impediment to the auditor’s professional scepticism. Practitioners confirm that an unfavourable opinion may compromise not only the audit business relationship but also the non-audit business and therefore perceive the provision of NAS as detrimental to auditor’s independence.

Prohibiting the simultaneous provision of audit and any non-audit services to the same client is the way forward. To eliminate this potential threat to independence, Commissioner Barnier in 2011 and the UK government in 2022 have suggested an operational split of the Big Four into separate audit and consultancy firms. Following the Wirecard failure, the responsible auditor EY is considering a break-up plan, too. However, a split-up in the Big Four cannot really address the problem of partiality. First, if the shareholders of the operationally separate firms remain the same, in practice it would still be the same company with a common business interest. Second, Non-Big Four firms may be even more vulnerable to conflicts of interest if they offer audit and NAS in parallel. Challenger firms have fewer clients, so a single client represents a significant source of revenue that they do not want to lose.A more sensible solution than the split-up in the Big Four is therefore to prohibit all auditors from providing any NAS to their PIE audit clients.

The “auditee selects and pays the auditor” problem can be mitigated through additional accountability towards shareholders. Under the existing business model for the provision of audit services, auditors are appointed and paid by the audited entity. The 2014 reforms partly addressed this inherent conflict of interest by strengthening the independence of audit committees and making them responsible choosing the auditor. This change was an important step in counterbalancing the influence of management, but it ignored the fact that the primary addressees of financial accounts and audit opinions are companies’ shareholders. To acknowledge the accountability of auditors towards shareholders, auditors should be required to present their findings at annual general meetings and answer questions raised by shareholders.

4.3 Establish effective oversight at European level

In Europe, audit supervision occurs mostly in the national domain. Strict public oversight can play an important role in ensuring audit quality and fostering confidence in financial reporting. The 2014 reforms strengthened the independence of national authorities, enlarged their competences, and empowered the CEAOB with cross-border coordination. However, the fact that oversight remained in the hands of national authorities becomes problematic because member states’ authorities have different resources and structures, and multinational audit firms are not properly supervised at the European level. This must change. Europe needs to establish an effective auditor oversight that is as powerful as the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) in the US or the planned Audit, Reporting, and Governance Authority (ARGA) in the UK.

ESMA should become the centre of European audit supervision. As pointed out by ESMA’s stakeholder group in the aftermath of the Wirecard failure, it would be legitimate to complement ESMA’s task of monitoring European financial markets with oversight of auditing.To effectively supervise firms operating across the EU, ESMA should exercise direct oversight of the biggest multinational audit firms, including the power to adopt sanctions. All other audit firms could remain within national supervision. As is established practice for the European Central Bank as single supervisor in the Banking Union, the oversight of the biggest audit firms in the EU should be organised in joint supervisory teams consisting of national experts and ESMA staff. If certain audit firms repeatedly perform poorly in ESMA's periodic inspections, it should have the power to exclude them from accepting new PIE audit engagements for as long as quality remains unsatisfactory. In addition, ESMA should be empowered to act in case the high concentration in the PIE audit market persists despite of reforms meant to reduce market entry barriers for challenger firms. Like ARGA in the UK, ESMA should have the power to cap the market share of the audit firms under its remit.

Crucial provisions of the European rulebook should be applied consistently across the EU. The existing legal framework allows for a multitude of national options. This fragmentation makes life difficult for audit firms that want to offer their services in more than one country, and it would demonstrate a substantial challenge for ESMA as single supervisor of the biggest audit firms. As a minimum, the introduction of mandatory shared and joint audits should therefore be accompanied by a harmonisation of the maximum rotation period for PIE audits. There are currently 17 different such regimes across the 27 EU member states. As the average audit firm tenure within the EU is between eight to nine years, it would be appropriate to keep the maximum rotation period of ten years but remove member states' option to extend it. The more uniformly the rules are applied, the better the European audit market will meet the goal of a Capital Markets Union.

5 Conclusion

The European audit market has been broken for too long now. The functional deficits that underpin the dominant position of the Big Four are well researched. To address them, European Commissioner Michel Barnier in the wake of the financial crisis set out bold reform proposals that had the potential to shake up the market. But the final set of changes adopted in 2014 lacked teeth and failed to get to the root of the problem. As a result, neither market concentration nor audit quality improved.

With the right tools, decision-makers can turn the audit market upside down. To finish the job, they should remove entry barriers for challenger firms that currently hinder competition. In particular, a binding requirement for, first, managed shared audits and, later, managed joint audits would strengthen the competitive positioning of Non-Big Four audit firms and at the same time improve audit quality. Furthermore, lawmakers should eliminate remaining conflicts of interest by prohibiting the simultaneous provision of audit and non-audit services. Finally, they should complete auditor supervision at EU level by entrusting ESMA with the oversight of the biggest audit firms, thus advancing the European Capital Markets Union.

A functioning audit market is crucial as the importance of audits is about to increase. With the corporate sustainability reporting directive (CSRD), the EU is rolling out requirements for companies to report on the sustainability of their activities – and auditors will be asked to provide assurance on the sustainability information. As a result, auditors' work will soon also determine the credibility of sustainability reporting and thus feed into the broader agenda of greening the European economy. So, Europe should fix the quality issues facing the audit profession rather sooner than later.