The Conference on the Future of Europe has put the extension of qualified majority voting (QMV) at the top of the EU’s reform agenda. The EU’s response to the invasion of Ukraine has underlined the pitfalls associated with unanimity. And the old debate on the balance between deepening and widening has come back with the prospective EU membership for Ukraine and Moldova. While the extension of QMV to the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is currently the most popular reform option for member states, there is no quick and easy path towards it. This policy brief discusses different paths and potential short-cuts. The member states should seize the current window of opportunity to explore different approaches and speeds for different sub-areas of CFSP and prepare a broader reform package for the medium to long term.

Introduction

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen started her term of office in 2019 promising a more geopolitical EU. She repeatedly called for the extension of qualified majority voting (QMV) to the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and tasked the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy / Vice-President of the Commission (HR/VP) Josep Borrell to pursue the matter. Two and half years into his term, Borrell said: “I cannot think of a single change that would have a more powerful effect to improve our ability to act in a hostile world”. Even so, little tangible progress has been made. The key problem is that the very introduction of QMV requires unanimity. So far, it has not even commanded a simple majority among member states.

Nevertheless, the issue is back on the agenda. The Czech Council Presidency started its six-month stint by sending out a questionnaire asking member states whether they are willing to consider an extension and, if so, in which policy areas. The outcome was mixed. Some member state representatives argued that the EU cannot afford another drawn-out reform debate now that it is facing myriad crises with a war on its doorstep, a looming recession and potential cuts in power supplies.

In this policy brief, I take the opposite view and argue that the current context makes a serious discussion on extension even more urgent. I then discuss two paths towards extending QMV and potential alternatives. While there is no quick and easy path, the current policy window should be used to explore short-cuts and various speeds for different sub-areas of CFSP.

1. Why now? Three drivers

The debate on the extension of QMV has been dragging on for years. However, as others have also noted, three factors are pushing open a potential policy window.

First, the Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFoE) has put the issue at the top of the EU’s reform agenda. The final report of 9 May 2022 states that all issues decided by unanimity should shift to QMV, except for the admission of new members to the Union and changes to fundamental EU principles. There is an expectation that the EU will follow up on the citizens’ preferences expressed in the conference. While this has triggered a broader discussion on the issue, analyses show that the extension of QMV to CFSP, while divisive, is still the most popular institutional reform option for member states. Extension is also front and centre of the European Parliament’s reform wish list. The only concrete Treaty amendments it proposed as a follow-up to the CoFoE concern the extension of QMV with a special focus on sanctions (see section 3.1).

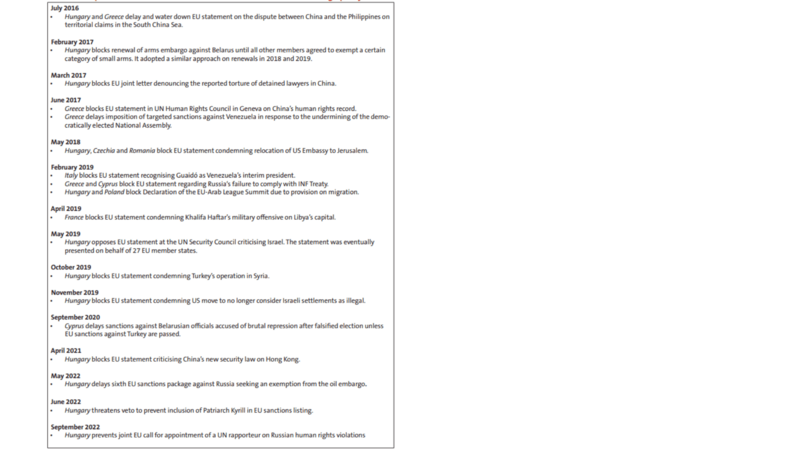

Second, the war in Ukraine shows just how detrimental the unanimity requirement is to the EU’s capacity to act. In spring, Hungary held up the EU’s sixth sanctions package, including an oil embargo on Russia, for weeks to secure an exemption. It then withheld agreement by refusing to include Orthodox Church Patriarch Kirill in the EU’s sanctions listing. In September, Hungary even threatened to derail the six-month renewal of the whole EU sanctions package and demanded that three oligarchs be removed from the listing. It also blocked a common EU call for the appointment of a UN rapporteur on Russian human rights violations. These are only the latest, but arguably the most significant examples of an array of cases (see Box 1) where a handful of member states has prevented the EU from speaking with a single voice on the global stage.

Box 1: Examples of how a few member states can block common EU foreign policy

Third, prospective EU membership for Ukraine and Moldova has put enlargement back on the agenda – and with it the old debate on the balance between deepening and widening. The French President, the German Chancellor and the European Commission President have all underlined that future enlargement must go hand in hand with internal reform and have regularly endorsed the passage to QMV. French and German endorsements have indeed been more forceful and explicit than in the past. The link between deepening and widening is relevant as many of the opponents of deepening, and with it an extension of QMV, are also strong proponents of fast-tracking EU enlargement. The balance between deepening and widening will undoubtedly shape the debate on the EU’s future during the months and years to come.

2. How to get there? Two paths towards QMV in CFSP

While the time may be ripe for QMV, the big question is of course how to get there. Two paths have been proposed and are being discussed by member states: Treaty change and the use of the passerelle clause within the existing legal framework. In the following, we discuss both options against the backdrop of member state preferences.

2.1 Real deepening via Treaty change

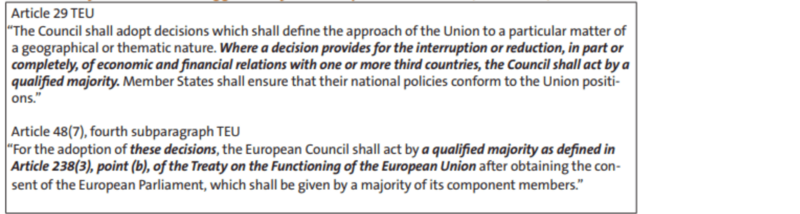

The first path is via Treaty change. In its resolution of 9 June 2022, the European Parliament suggested two amendments (see Box 2). First, it proposed amending Article 29 TEU by inserting the possibility to impose economic and financial sanctions via QMV. The second and more far-reaching amendment aims at changing the general passerelle clause (Article 48(7) TEU) – not to be confused with the CSFP-specific passerelle clause discussed below – and suggests switching from unanimity to an enlarged or super-qualified majority as defined under Article 238 (3) (b) TFEU. In this case, 72% rather than 55% of member states, or 20 rather than 15, comprising at least 65% of the population, would have to agree. Borrell even proposed introducing a new type of ‘super-super qualified majority’ consisting of “27 minus 2 or 3”.

Box 2: Treaty amendments suggested by the European Parliament (June 2022)

Former MEP Andrew Duff recommended an important addition that the European Parliament left out of its June resolution. He suggested amending the third subparagraph of Article 48 (7) TEU under which any national parliament could block the use of the general passerelle clause within six months of the European Council decision. If this clause remained in place, resorting to the passerelle clause would remain highly unlikely.

The suggested Treaty change would pave the way towards real deepening and could be part of a broader package deal. As Czech Minister of European Affairs Mikuláš Bek said at the press conference following the General Affairs Council meeting, a package combining an attractive set of items regarding institutional and electoral reforms, decision-making and enlargement could ease the path towards QMV.

Even so, there is no quick and easy path towards Treaty change. For CFSP, only the ordinary revision procedure is an option. The simplified revision procedure under Article 48(6) TEU, which is decisively faster, is reserved for the Union’s internal policies. There are three hurdles with the ordinary procedure. The first is triggering the process, which requires a simple majority in the European Council. Its President shall then convene a Convention composed of representatives of the national parliaments, of the Council, of the European Parliament and of the Commission. While Parliament and Commission support holding a Convention, the Council is divided. Seventeen member states are reportedly opposed. These include the thirteen countries that have expressed their scepticism in a non-paper in May, namely Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and Sweden. The second hurdle is negotiating and agreeing on a package by unanimity. The third and final hurdle is ratification, which entails adoption by all national parliaments and referendums in some countries. The whole revision process would thus be open-ended and take years.

2.2 Gradual extension of QMV via the CFSP-specific passerelle clause

The quicker path to QMV would lead via the passerelle clause specific to the CFSP (Article 31(3) TEU). The European Council can thereby unanimously decide to extend QMV to specific fields within CFSP. There are two limitations. First, this does not apply to decisions with military or defence implications. Second, there is an emergency brake (Article 31(2) TEU) whereby any member state can object to a decision being taken by QMV for “vital and stated reasons of national policy”. In this case, the HR/VP and the member states involved are enjoined to search for an acceptable compromise. If they fail, the Council can, acting by QMV, refer the issue to the European Council for a decision by unanimity.

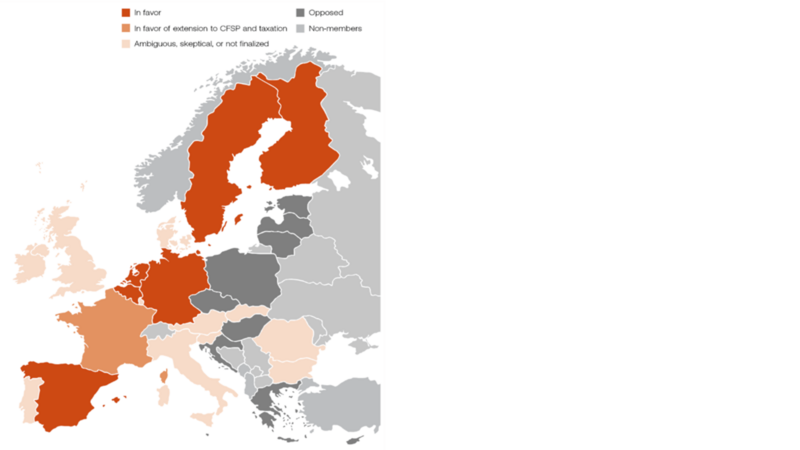

Based on the passerelle clause, the Juncker Commission proposed the gradual extension to three areas of EU foreign policy in 2018: EU positions on human rights in multilateral fora; the adoption and amendment of EU sanctions regimes; and the civilian Common Security and Defence Policy (CSPD). The proposal was met with limited enthusiasm among member states. An expert survey we conducted in 2019 showed that only seven Western member states were in favour, while ten were sceptical/ambiguous and another ten, mostly Eastern and Southern member states, were outright opposed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Member state positions on the extension of QMV to CFSP via the passerelle (2019)

Support has now slightly increased. At the General Affairs Council meeting of 20 September 2022, “most of the ministers were open to consider the use of passerelle clauses in certain fields, on a case-by-case basis.” A Council document seen by Politico indicates that they were most open to using the passerelle for CFSP, notably sanctions, human rights and civilian CSDP, and less so “for taxation, energy policy and non-discrimination matters”. According to an overview by MEP Daniel Freund, ten member states supported the move to QMV in EU foreign policy while nine were silent and eight opposed. Overall, there is a greater openness towards the extension of QMV to sanctions and human rights than for CSDP. Several member states in the neutral or sceptical camps, notably Latvia, Portugal, Ireland, Cyprus and Croatia, voiced explicit opposition to QMV within CSDP.

While we are still a long way away from unanimity, the difference between 2019 and 2022 shows that positions on QMV are not set in stone. Central and Eastern European countries have seen the downsides of single vetoes delaying or watering down the EU’s response to Russia. According to the Freund overview, two countries – Slovenia and Romania – have already joined the pro side. Others that remain sceptical of an extension of QMV could also shift. Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis accused Hungary in May 2022 of “holding the EU hostage”. Meanwhile, an Estonian study, commissioned by its parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee, cautiously recommended a passage to QMV in CFSP. The Committee's chair then announced a comprehensive discussion of the matter this autumn. There also seems to be cautious openness in smaller and neutral states such as Ireland, Austria and Malta to at least engage constructively in the discussion.

3. Three alternative paths

Both paths outlined above will take time and it is uncertain whether and when they will yield results. This raises the question of alternative paths and workarounds. In the following, we focus on the three options that are most frequently discussed in the context of the CFSP.

3.1 Flexible implementation

Treaty provisions allowing for flexible implementation once the European Council or Council have provided a unanimous vote could come closest to a second best option. This includes the enabling clause (Article 31(2) TEU) whereby the European Council can allow the Council to implement a decision relating to the Union’s interests by QMV. Potential examples include sanctions listings, the implementation of civilian CSDP missions or aspects of thematic or geographic strategies agreed by the European Council.

The enabling clause has found application in the field of EU sanctions. The Council has occasionally agreed on the amendment of sanctions listings by QMV in the past. In 2018, the Commission suggested that the Council should amend all listings by QMV. However, as the most recent struggles on this issue in the Russian case indicate, such amendments can be highly controversial. Another interesting attempt to extend QMV in the field of sanctions concerned the implementation of the EU Action Plan for Human Rights and Democracy of 2020. The European Parliament, Commission and HR/VP recommended implementation by QMV in the Council after the European Council sets strategic objectives. This would, for instance, have applied to the Plan’s first concrete deliverable: the EU framework for human rights sanctions or European Magnitsky Act. However, the member states eventually opposed the extension of QMV to this sub-area of EU sanctions policy.

Another interesting option that is specific to the CSDP is Article 44 TEU. It allows the Council to unanimously entrust the implementation of a mission or operation to a group of willing and able member states that would then agree among themselves on its management. The provision has never been used. This could change in the future. With the Strategic Compass for Security and Defence, the member states agreed to “decide on practical modalities for the implementation of Article 44” by 2023.

The problem with both these options is that, like the passerelle clause, they require a unanimous decision in the first place. The same applies to enhanced cooperation within the CFSP (Articles 20 TEU and 326-333 TFEU). Establishing it not only requires a minimum of nine participants, but within the CFSP a unanimous authorisation by the Council on top. Some argue that enhanced cooperation could be an easier alternative to the passerelle clause. Once established, the participants can agree among themselves to switch to QMV (Article 333 TFEU). The decision would then bind the participants alone. While this sounds good in theory, the question is where it could realistically be applied. Enhanced cooperation has never been used in CFSP and Article 333 TFEU also excludes decisions with military and defence implications. As for the other two clauses, it can only be used if the initial decision/dossier is pretty well uncontroversial.

3.2 Constructive abstention

The alternative to the specific passerelle clause under Article 31(3) TEU that generates less controversy among member states is constructive abstention. Article 238(4) TFEU generally allows member states to abstain in a unanimous Council vote. A constructive abstention as defined in Article 31(1) TEU allows them to qualify their non-vote by making a formal declaration. In this case, the abstaining member is not obliged to apply the decision but accepts that it commits the Union and shall refrain from any action that would impede or conflict with the decision.

Constructive abstention has only been used twice and only in the context of the CSDP. The first case was the abstention by Cyprus in 2008 regarding the Decision to establish the EU’s civilian rule of law mission EULEX Kosovo. The second, and more recent example concerns the European Peace Facility, the financial instrument under which the EU has provided Ukraine with €2.5bn worth of lethal and non-lethal military assistance between February and July 2022. Ireland, Austria and Malta constructively abstained regarding lethal assistance but contributed to non-lethal support.

Constructive abstention allows member states to adhere to national specificities (e.g., neutrality) without blocking the path for the others. It is, however, unhelpful if one or a few member states explicitly seek to do so to protect national strategic or economic interests.

3.3 Intergovernmental cooperation

Considering the limitations of the options above, member states often resort to intergovernmental cooperation. This included diplomatic core groups such as the E3 (France, Germany and the UK) in the negotiations on the Iran nuclear deal. The intergovernmental path can also be a way out when it comes to diplomatic or human rights declarations. When Hungary for instance prevented a joint EU call for the appointment of a UN rapporteur on Russian human rights violations, the other 26 members issued the call via their national delegations.

Member states have also formed European military coalitions of the willing outside the EU framework. Examples include operation Agénor in the Straits of Hormuz and Task Force Takuba in the Sahel. However, these European coalitions of the willing have downsides. They are generally perceived to be less legitimate than CSDP operations and enjoy no common funding. In addition, some member states cannot join for legal reasons. According to the German Constitution, for instance, the Bundeswehr can only be deployed abroad as part of a system of collective security.

Finally, the intergovernmental path is closed for EU sanctions – a growing and key component of EU geo-economic power.

Conclusion and recommendations

While the extension of QMV to CFSP is the most popular reform option, there is no quick and easy path towards it. Nor are there very good ways around it. Member states should still seize the current window of opportunity to explore potential shortcuts and prepare the path for medium to long-term eventualities. The map of member state preferences suggests that they should also consider different approaches and speeds for different sub-areas of CFSP.

In the short-term, they should explore the full potential of flexibility clauses within the Treaties. Member states have already agreed to do so for the CSDP with the Strategic Compass for Security and Defence. This includes constructive abstention, where the European Peace Facility set an important precedent. Member states are also preparing the ground for the establishment of European coalitions of the willing under Article 44 TEU. They have until 2023 to discuss scenarios and practical modalities. They should use the time to clarify the benefits of the EU framework (e.g., the possibility to make use of the EU’s planning and conduct structures and to receive funding under the European Peace Facility). In addition, they should grant participants greater leeway. The current interpretation of Article 44 emphasises political control by the Council and restricts the degree of flexibility during implementation.

In the short and medium term, the advocates should also keep pushing for the gradual extension of QMV in CFSP via the passerelle or enabling clauses. The focus should be on sanctions where the impact would be highest. In this field, the pitfalls associated with unanimity emerged starkly with the response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In addition, the member states’ red lines are less bold than for CSDP. France and Germany should take the lead in reaching out to the large group of member states that still sit on the fence regarding the use of the passerelle clause. They should pay particular attention to the justified concerns of smaller member states. The bigger challenge will be to convince members such as Hungary and Poland that oppose the passage to QMV partly for ideological reasons.

An interesting parallel path that could yield results in the medium term is the review of the EU’s counter-sanctions regime. In this area, EU foreign and trade policy increasingly intersect. After Lithuania opened a “Taiwan Representative Office” in Vilnius in 2021, it faced massive economic coercion by China. Based inter alia on this experience, the Commission proposed the Anti-Economic Coercion Instrument in 2021. This new tool would allow for economic countermeasures if a member state experienced economic blackmail by a non-EU country in response to a particular policy choice or position. The Commission located the instrument within the field of trade and thus suggested decision-making by QMV. Once agreed, it could become a very useful tool in a drawn-out economic confrontation with Russia and represent an important (and potentially quicker) supplement to CFSP sanctions agreed by unanimity.

A broader and durable extension of QMV to CFSP via the passerelle clause or Treaty change is only realistic in the longer term and will have to be part of a cross-issue package deal. Beyond the abstract link between enlargement and reform, the question is which concrete items would be attractive enough to convince the opponents of deepening integration. If the European Council decides against triggering a Convention in the short term, it should, as suggested by former MEP Duff, at least establish an autonomous wise persons group that could tease out the components of a viable package deal to prepare the way for reform.