In May 2024, the European Parliament will be directly elected for the tenth time. After the Conference on the Future of Europe, it is the next big test for supranational democracy. In this policy brief, Dr Manuel Müller offers an overview of what to expect from the election: On which date will it take place (and why does that matter)? What electoral law will apply? Will the lead candidate procedure come into play again? How are the European parties doing in the polls? And of course: What will happen with voter turnout?

Introduction

Tomorrow always comes sooner than you think – and so does the next European Parliament (EP) election, which will take place in almost exactly two years. For the tenth time since 1979, voters will be called to the polls to choose the members of the EU’s only directly-elected supranational institution. After the big participatory experiment of the Conference on the Future of Europe, this will be the next important practical test of democracy at the European level. While past EP elections have often suffered from strong national fragmentation and a reputation for being “second-order” votes, they are still the central legitimising act through which all European citizens can have a say in the political direction of the EU.

Politically, the election casts a long shadow. Electoral reforms are being discussed; candidates are pondering their chances. And as is almost always the case with EU elections, the inter-institutional struggles are no less important than the party-political competition. This policy brief looks ahead to 2024 and provides an overview of the state of play: What institutional questions remain to be solved over the next two years and what can we expect from the election?

When will the election take place? The importance of timing

The exact date of the election is not yet fixed. EP elections take place over a four-day period from Thursday to Sunday, within which each member state can determine its own election day (or days). Initially, this period took place in early June, which is still the legal default. However, the Direct Elections Act allows the Council to move the date to any time between early April and early July through a unanimous decision up to one year before the election. Since 2014, it has become customary for EP elections to take place during the last week of May.

Within the EP, many would like to bring the date even further forward – for example, to the week around Europe Day on May 9th. This shift would not only have symbolic value, but also relax the timeline for the appointment of the Commission during the summer. After its opening session (which according to the Direct Elections Act takes place on the first Tuesday of the month after the election), the EP first elects the Commission President nominated by the European Council. Subsequently, each national government proposes a Commissioner, and the designated President distributes the portfolios among them. The EP committees then hold hearings to assess the qualifications of the proposed Commissioners and may request the replacement of some candidates. Finally, the EP plenary holds a vote to officially elect the College of Commissioners.

The entire procedure should be completed before the previous Commission’s five-year term of office ends on October 31st; in 2019, however, it dragged on until late November. The resulting time constraints put the EP under political pressure to avoid a crisis and approve the proposed candidates as quickly as possible. Additionally, an attempt of the four major parliamentary groups to set out a common legislative agenda before voting on the Commission presidency failed because they lacked time to overcome programmatic differences. Thus, the timing of the election also affects the inter-institutional power balance between the EP and the European Council: an earlier election would strengthen the EP’s hand in both the composition of the next Commission and the definition of its legislative working programme.

By what electoral law? Two main reform proposals

Regarding the electoral system, the EP elections currently consist de facto of 27 separate national elections, in which each member state has a fixed seat contingent – ranging from six for Malta, Cyprus and Luxemburg to 96 for Germany. While the Direct Elections Act sets out some general EU-wide rules for the election (for example, the proportional allocation of seats within each constituency), many important aspects (such as the number and size of constituencies, the voting age, campaign financing rules, electoral thresholds, etc.) are determined by the national electoral laws of each member state. Moreover, the existence of national constituencies implies that the lists of candidates in each member state are drawn up by the national parties, and usually only the names of the national parties appear on the ballot paper.

In order to overcome this fragmentation, members of the European Parliament have long pushed for a new European electoral law. However, the Direct Elections Act has not been amended since 2002 – not least because its reform is a cumbersome procedure which requires a unanimous Council decision supported by the EP and ratified by all national parliaments. Currently, two reform proposals are on their way through the legislative process.

First, in 2018, the Council unanimously passed an amendment which, among other things, obliges the largest member states to have a national electoral threshold of at least 2 per cent of the votes. However, this reform is still to be ratified by Germany, Spain, and Cyprus, and might encounter constitutional obstacles particularly in Germany, where the Federal Constitutional Court has repeatedly rejected an electoral threshold for EP elections. And even if it were to enter into force before 2024, the obligation to have a national threshold would only come into effect for the 2029 elections.

Second, an even more ambitious reform of the Direct Elections Act was proposed by the EP in early May 2022 and will now be discussed by the Council. Most notably, this proposal includes the introduction of a new EU-wide constituency of 28 seats, for which European political parties would draw up transnational lists. Other reform elements are, for example, new rules for gender quotas on electoral lists and a common single voting day on May 9th, as well as a harmonisation of the minimum voting age and of postal voting procedures. All in all, this reform package would not result in a completely unified electoral system, but it would be an important step towards the “Europeanisation” of EP elections.

Still, although the EP would like to see the reform implemented before the 2024 election, it is unlikely that this will happen. According to the Council of Europe’s Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters, electoral rules should not be changed less than one year before an election, which reduces the timeframe for an agreement to summer 2023 – and in the Council, many governments are still very reluctant to approve the reform. Thus, the most probable scenario is that the same European electoral law will apply for the elections in 2024 as in 2019.

Will the Europarties nominate lead candidates again? The issue with the Spitzenkandidaten

Not all changes of the electoral procedure require a legal reform, however. In practice, the most important electoral innovation of recent years has been the nomination of lead candidates (Spitzenkandidaten) for the Commission presidency by the European political parties. In the 2014 and 2019 EP elections, voters were promised that the choice of Commission President would be determined by the electoral results.

Still, the European Council never quite accepted the new procedure, and after the 2019 election, the various parliamentary groups failed to form a majority behind any of the lead candidates. Consequently, Ursula von der Leyen, who had not been nominated as Spitzenkandidat in the lead-up to the elections, was elected Commission President. This led some commentators to assume that the lead-candidates procedure was “dead”. But the major Europarties have not abandoned the approach. Given that the procedure is not legally enshrined but rather based on a political commitment by the parties themselves, there is nothing that can prevent them from nominating lead candidates again. The institutional tug-of-war over the Spitzenkandidaten is therefore likely to continue in 2024 – with many implications for European democracy. Although the Spitzenkandidaten have so far not met all expectations in terms of public visibility, they have certainly changed the dynamic and increased the stakes of EP elections.

The possible names of the lead candidates are still very much a matter of speculation. A special situation could arise if Ursula von der Leyen decides to run for a second term. In this case, the European People’s Party (EPP) would probably nominate her as the lead candidate. It would be the first time that an incumbent Commission President campaigns publicly as a Spitzenkandidat, which could give the procedure additional visibility. And if the EPP were to become the strongest parliamentary group once again, the European Council would hardly oppose her re-election. This is certainly true for the government of her home country, Germany: although von der Leyen’s own party, the CDU, is now in opposition, the coalition agreement includes a clause that gives the Green party the right to nominate the German Commissioner unless the Commission President comes from Germany – thus implying support for von der Leyen’s possible re-nomination.

How are the election polls? Changing trends since 2019

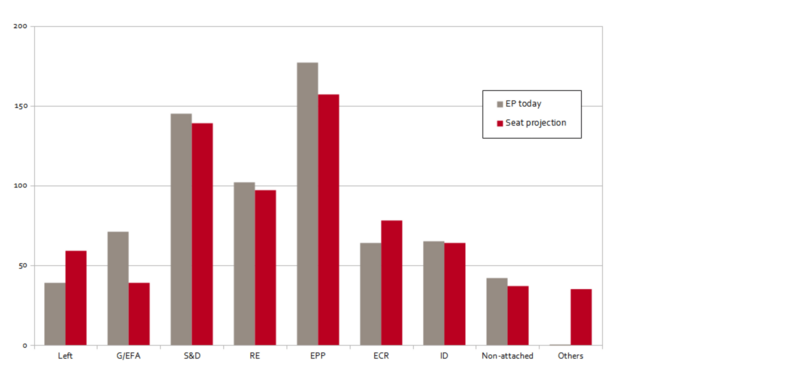

Whether the EPP will really win the election is still a wide-open question, however. There are no EU-wide electoral polls, but several websites – Europe Elects, Politico, and Der (europäische) Föderalist – regularly publish seat projections for the European Parliament based on national polls from all member states. Although these seat projections use slightly different methodologies, they all suggest that the EPP’s lead over the centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D) is dwindling. If the race remains this tight, the S&D could have a chance to recover the position as the strongest parliamentary group for the first time since 1999.

More generally speaking, both the EPP and the S&D are weaker now than in 2019, following a long-term trend of decline of the two largest parliamentary groups over the last two or three decades. Among the other groups, the Left and the right-wing European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) would gain seats, while the Greens/European Free Alliance (G/EFA) would lose seats. The centrist Renew Europe (RE) and the far-right Identity and Democracy (ID) are polling at similar levels as in 2019. Overall, the current trends would not lead to fundamental changes in the balance between the centre-left and the centre-right camps.

Eurosceptic parties might once again increase their combined weight, but they continue to be very far from a parliamentary majority. Given that the far right is currently divided in two parliamentary groups (ID and ECR) as well as several non-attached parties, speculation about a possible merger into a big right-wing Eurosceptic group has been ongoing for years and might re-emerge again before the election. However, preliminary talks among party leaders already failed in 2021 due to internal rivalries. Now that the war in Ukraine has driven a wedge between the more pro-Russian ID (with the French Rassemblement National, the Italian Lega, and others) and the more anti-Russian ECR (dominated by PiS from Poland), things do not look any more promising for a unified far right. While some poaching and switching of individual national parties can be expected, the Eurosceptic front will probably remain an elusive spectre in 2024 as well.

Finally, since the last EP election, strong newcomer parties have emerged in several member states – such as Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, and Slovenia. In 2024, many of them will enter the EP for the first time and try to join a European party family. However, given that these newcomer parties represent a variety of ideologies across the entire political spectrum, they are unlikely to upset the overall balance between parliamentary groups.

Of course, seat projections are just snapshots of the current political mood in Europe. The electoral polls could still shift significantly in any direction over the next two years.

Chart 1: European Parliament seat projection, Der (europäische) Föderalist, April 2022. Source: Der (europäische) Föderalist.

Will voter turnout increase again? The importance of electoral campaigns

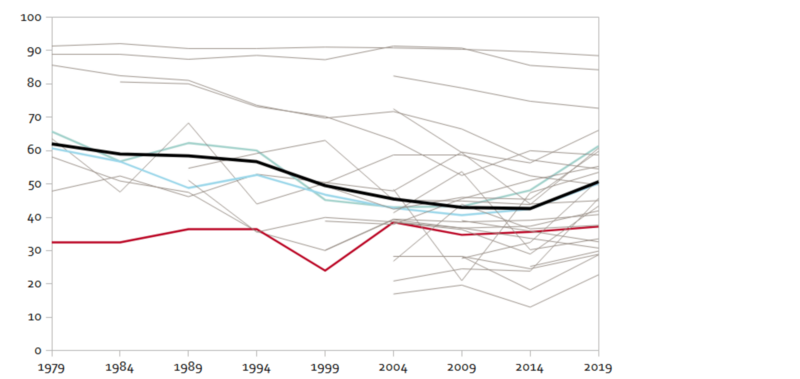

Another big question for the 2024 elections is voter turnout and how to incentivise voters to cast their ballots. Until 2014, EU-wide turnout had steadily declined in every election, suggesting an increasing disenchantment with and detachment from democratic mechanisms at the EU level. However, a sharp uptick in 2019 put this pessimistic diagnosis into perspective.

But in fact, the development of voter turnout within single member states has never shown such a clear picture. Turnout varies strongly between countries, and also between election years within the same country. A significant part of the decline up to 2014 was due to the accession of new member states with rather low turnout numbers. Conversely, it is possible that in 2024 EU-wide voter turnout could rise again for similar statistical reasons: it will be the first election without the United Kingdom, which traditionally has had a very high share of non-voters in EP elections. This means that even if turnout remains unchanged in all other member states, the European average will mathematically increase.

Chart 2: Voter turnout at EP elections. The bold line represents the EU average, every thin line a member state. Green: Germany, blue: France, red: United Kingdom. Data source: EP.

But other factors play a role, too. The relatively high turnout in 2019 resulted from a combination of several elements: simultaneous national elections in several member states, an intense awareness campaign especially in the largest member state Germany, widespread scare of a victory for right-wing Eurosceptic parties after the Brexit referendum and the US election in 2016, and the generally increased politicisation and polarisation of EU affairs since the “polycrisis”.

While some of these factors might have been a one-off occurrence, the politicisation of the EU is certainly here to stay. Compared to national parliaments, the EP only has very limited agenda-setting power: it not only lacks a right of initiative (which lies solely with the Commission), but also needs to find agreements with the Council for the adoption of any legislative act. In the past, parties have therefore struggled to make clear promises on EU issues during the electoral campaign. Instead, campaigns have often focused on parties’ general positions towards European integration – “for” or “against” the EU – or on completely unrelated national issues.

In the 2024 election, by contrast, there will be no lack of salient European issues. Topics like the rule of law crisis, the budget deficit rules, the European Green Deal, or the crisis of the common asylum system are not just a matter for Brussels-based experts but are being discussed in the national public arenas as well. Similarly, external border protection and issues of foreign and security policy like the war in Ukraine are increasingly seen as European rather than only national affairs. Finally, the Conference on the Future of Europe has produced an extensive set of reform proposals in many policy areas which parties will be able to take up in their campaigns. Combined with a more effective use of their Spitzenkandidaten, this could increase voter turnout by turning the 2024 election into a real competition to find solutions for political questions that matter to all European citizens.

Conclusion: The European Parliament election 2024 – more salient than ever?

Two years ahead of the EP election, many questions remain unanswered, and many inter-institutional disputes still need to be worked out. Although the European Parliament recently reached a ground-breaking internal agreement on transnational lists, it is unlikely that its proposals on electoral reform will soon find the necessary unanimity among national governments. Similarly, we can expect European parties to nominate lead candidates again in 2024, but it might once again be impossible to assess the real political significance of this procedure until after the elections. If Commission President Ursula von der Leyen decides to run again and the polls tighten further, the EP election may turn into an exciting duel between the EPP incumbent and a socialist challenger. But, as in 2019, it could be a long summer before the dust settles and a new Commission is sworn in.

One thing that seems clear, however, is that EU policy has steadily become more salient in recent years and that European voters today have a better understanding of what is at stake in the EP. This opens an opportunity for an electoral campaign in which topics of common relevance could play a more important role than ever before. Although it is of course impossible to anticipate which exact issues will shape the public debate in 2024, it is quite certain that EU policy will be no less important than it is today. It will thus be up to the European parties to elaborate transnationally-shared positions and give them public visibility in order to allow voters a clear choice between alternative policy proposals. If they achieve this, the 2024 European Parliament election can be an important step forward on the road to supranational democracy.

Manuel Müller is a postdoctoral researcher in European Integration & Politics at the University of Duisburg-Essen and blogger of the German-language blog "Der (europäische) Föderalist".